Long-term outcome for achalasia in patients who

underwent laparoscopic Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication

Mohammad

Taghi Ashoobi 1, Mohammad Sadegh Esmaeili Delshad 1,

Afshin Shafaghi 1, Manouchehr Aghajanzadeh 1*

1 Inflammatory

Lung Diseases Research Center, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine,

Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Manouchehr Aghajanzadeh

* Email: manouchehr.aghajanzadeh.md@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder that can require

surgical intervention in some cases. This retrospective cross-sectional study

aims to evaluate the clinical symptoms of patients with advanced achalasia who

underwent laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) and Dor fundoplication.

Materials and Methods: The study included 86 patients (38 men, 48 women) diagnosed with

achalasia between 2010 and 2020, of which 20 patients with advanced achalasia

underwent LHM and Dor fundoplication. The median follow-up time was 48 months.

Results: The study found that LHM and Dor fundoplication surgery improved

dysphagia in 12 patients, with four patients showing improvement in solid food

dysphagia and two patients showing improvement in semi-solid dysphagia.

Nocturnal cough and slow emptying sensation also improved in 16 cases.

Additionally, barium stasis decreased significantly in 14 patients. However,

two patients who underwent esophagectomy had hospital mortality.

Conclusion: This study highlights the effectiveness of LHM and Dor fundoplication

in reducing dysphagia, nocturnal coughing, regurgitation, and other obstructive

symptoms in patients with advanced achalasia. However, the study also

underscores the potential risks associated with esophagectomy, suggesting that

surgical treatment for achalasia should be carefully considered on a

case-by-case basis.

Keywords: Achalasia, Dysphagia, Heller myotomy, Fundoplication, Gastroesophageal

reflux

Introduction

Achalasia is an uncommon but quintessential esophageal motility

disorder that occurs equally in men and women (1). Achalasia

characterized by reduced relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and

absence of esophageal peristalsis resulted in impaired bolus transit,

demonstrated with symptoms including dysphagia, retrosternal pain,

regurgitation, and weight loss (2).

The disease’s pathogenesis is unclear and often misdiagnosed (3). Still, it is

suggested to happen because of a virus-related inflammatory neurodegenerative

process triggered by an autoimmune and chronic inflammatory process, especially

in patients with genetic susceptibility (4). However, at

the time of diagnosis, the number of decreased neurons led to significant

dysfunction and symptoms. Therefore, the first step of diagnosis is performing

endoscopy or radiology, but the gold standard diagnostic method for achalasia

is high-resolution manometry (HRM) (5).

According to Chicago classification, achalasia is classified into

three subtypes, type I (classic achalasia) refers to the one without any

significant pressurization in esophageal, type II is achalasia with

compression, which there is no peristalsis and contractile activity, and

pan-esophageal pressurization >30 mmHg, and type III is spastic achalasia

with rapidly propagated pressurization attributable to an abnormal lumen

obliterating contraction (6).

As achalasia progresses, dilation of the esophagus worsens and can

resemble a sigmoidal shape. In the end stage of achalasia, patients present

dilation of the esophagus with a sigmoid shape (7).

Unfortunately, there is no promising treatment for achalasia due to its unknown

pathogenesis, and standard treatment options include pharmacological therapy

(nitrates and calcium channel blockers), pneumatic dilation, endoscopic myotomy

(2,3), Botulinum

toxin (Botox) (8), surgical

myotomy, and esophagectomy (2,3).

Surgical treatment of achalasia has evolved dramatically over the

past 13 years. Since the first report of laparoscopic Heller myotomy by

Cuschieri and thoracoscopic Heller myotomy by Pellegrini, minimally invasive

surgery has become the gold standard for treating achalasia (9). More

recently, the laparoscopic management of esophageal achalasia has achieved

widespread acceptance and is now the first line of therapy for patients with

achalasia. The satisfactory short-term results of this procedure are well

documented in several large series.

Esophagectomy is more aggressive and associated with more

significant morbidity/mortality than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) and Dor

fundoplication (10). In this

regard, we study the post-surgical side effects and clinical symptoms of

patients in two groups who underwent LHD and Dor fundoplication in patients with achalasia.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study was

conducted on 86 patients with achalasia in Razi Hospital, Rasht, Iran, from October 2010 to September

2020. The achalasia was confirmed by clinical findings (endoscopy, radiology, and HRM

results). In addition, all demographical data and clinical characteristics of

patients were recorded from the patient’s archive in the hospital.

The surgery approach was LHM (8 cm over the esophagus and 3 cm over

the stomach) and Dor fundoplication (Figure 1). All remnant food was aspirated

to prevent pulmonary aspiration after induction of general anesthesia with a

tracheal tub. Before the surgery, 16 of the patients had undergone previous

dilatations or Botox injections. Longitudinal and circular muscle of the

esophagus was cut on the last 8 cm of the esophagus and extended three cm on

the gastric wall musculature. Dor fundoplication was performed in all patients.

In our study, the perforation and complete myotomy were checked after

completion of cardiomyotomy with an ambo-bag, and via a tube in the esophagus

air inflate. Postoperative assessments include clinical, radiologic,

manometric, and endoscopic evaluation was performed.

A flap of the stomach for coverage was fixed to prevent diverticula

formation in the motorized site. Pre and post-operative assessment included

symptoms, esophageal emptying observation with barium esophagogram, HMR, and

endoscopic evaluation in all patients. The barium esophagogram was obtained

under fluoroscopic control.

Figure 1. Laparoscopic

Heller myotomy in patients with achalasia.

The surgical technique for laparoscopic Heller myotomy was after

the pharyngoesophageal ligament that divided the fat pad excised and exposing

the anterior gastroesophageal junction; the myotomy was performed by incising

the distal 4 to 6 cm of esophageal musculature. Then, the myotomy was extended

2 to 3cm onto the gastric cardia using cautery scissors with an

intraesophageally tube; when the EJ junction closed, the esophagus was

inflated, mucosal perforations were detected, and the myotomy added a Dor

anterior hemifundoplication. Routinely, a contrast swallow was performed on the

second day of postoperative in all patients to rule out an occult leakage. For

patients with no leak, a clear liquid diet was started on the second

postoperative day, and all patients were discharged four days postoperatively.

The results were reported in number and percentage.

Results

Among a total number of 86 patients (38 males, 48 females) with a

median age of 46 years old, patients had advanced achalasia including lumen

dilatation of esophagus between 6 to 12 cm, moderate to severe intra luminal

stasis of barium, severe tortoise, recurrent pulmonary aspiration, and

recurrent pulmonary infection; and underwent laparotomy for achalasia. These

patients failed in pneumatic dilatation and Botox treatment. Dysphagia

presented in all patients, and 20 patients experienced an average weight loss

of 10 kg before surgery. Pre-surgical clinical characteristics of patients are

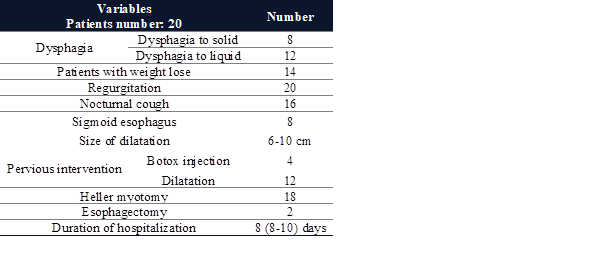

demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Pre-surgical

clinical characteristics of patients with achalasia.

Two patients expired, one during operation and another one in five

days after surgery due to pneumonia and reparatory failure. Two patients

required reoperation for bleeding and gastric herniation. Six patients

experienced minor postoperative morbidity, including atelectasis (3n), atrial

tachyarrhythmia (4n), and wound infection (3n). The median follow-up days

were 30 months (10–48 months).

According to our results, stasis was reported in all patients

before the operation. The LES gradient decreased from 32 to 12 mmHg. Endoscopy

and biopsy findings demonstrated grade I esophagitis in four patients. Radiological findings represented that barium

stasis decreased from 92% to 22%. The post-surgery diameter of the esophagus

lumen was 8 cm (8–12 cm), which fell to 6 cm (6-10 cm). Body weight increased

after the myotomy [preoperative: 58 kg (38–83 kg), postoperative: 66 kg (48–86

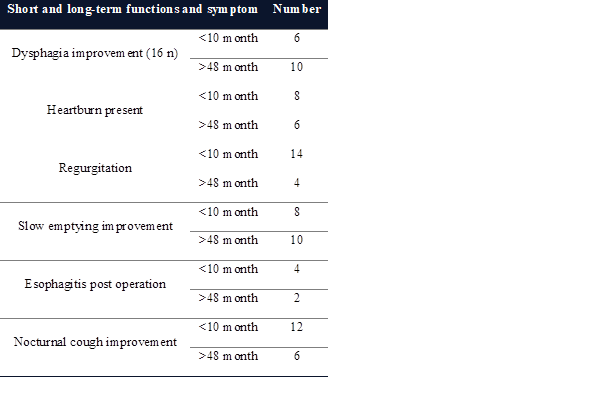

kg)]. No diverticular formation was observed in the motorized zone. Short and

long-term functions and symptom improvement in patients with achalasia are

illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Short and long-term functions and symptom improvement in patients

with achalasia.

Discussion

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder for which there is

no known etiology, making treatment options challenging. The main goal of

treatment is to reduce LES pressure, improve dysphagia and regurgitation,

enhance esophageal emptying, and prevent the development of megaesophagus.

Surgical management of advanced achalasia is challenging, and esophagectomy is

associated with a high incidence of postoperative respiratory complications

such as pneumonia. Our results aillustrated that LHM is an effective treatment

with a higher patient survival rate and fewer complications.

Previous studies have reported that higher LES resting pressure is

associated with better relief of dysphagia after myotomy. The LHM–Dor procedure

provides satisfactory long-term results with low morbidity (11,12). Esophagectomy was associated with

a high incidence of postoperative respiratory complications, including

pneumonia, while LHM is more effective with a higher patient survival rate (13,14). Arain et al. reported that higher

LES resting pressure is associated with better relief of dysphagia after

myotomy (15). A study demonstrated that

extending myotomy three cm over the stomach reduces the postoperative pressure

on the LES with no significant difference in reflux when added an anti-reflux

procedure (16). Also, Liu et al. reported that

esophageal myotomy for achalasia could reduce the resting pressures of the

esophageal body and LES and improve esophageal transit and dysphagia (17).

Dor fundoplication added to myotomy reduces the risk of pathologic

gastroesophageal reflux, and our study showed that it could be performed in all

patients with a low incidence of reflux. Studies have reported favorable

responses in more patients even after a long term of follow-up. LHM and Dor

fundoplication balance emptying and reflux and could be the selected surgical

treatment for patients with achalasia (12,18). In an investigation on a series of

73 patients treated with LHM, favorable responses were reported in more than

half of the patients, even after over six years of follow-up (19). Siow et al. demonstrated in their

study that LHM and anterior Dor fundoplication are both safe and effective as a

definitive treatment for treating achalasia cardia with high patient

satisfaction with minimum complications (20). A study by Finley et al. reported

that 24 patients who underwent LHM without fundoplication had more significant

improvement in esophageal clearance time (21).

Rice et al. represented that the addition of Dor

fundoplication decreases the capability of LHM without impairing emptying and

reduces reflux. LHM and Dor fundoplication balance emptying and reflux, which

could be the selected surgical treatment for patients with achalasia (22). Kummerow et al. illustrated no

statistical difference between patient-reported dysphagia or reflux scores in

those who underwent an LHM with and without Dor fundoplication (23). In this present study, reflux was

reported in nine patients with Do fundoplication. Also, end-stage achalasia

treated by LHM with Dor fundoplication showed reduced LES gradient, decreased

obstructive symptoms, and improved esophageal emptying.

Performing LHM is an effective treatment with good dysphagia relief

and a low incidence of esophageal mucosal perforation (24). Abovementioned studies reported

that LHM is an effective treatment with good dysphagia relief and a low

incidence of esophageal mucosal perforation. While manometry is sometimes essential

for good surgical outcomes, long-term follow-up on dysphagia relief and patient

satisfaction is necessary to ensure the effectiveness of therapy. Overall, our

study showed that LHM and Dor fundoplication are safe and effective treatments

for advanced achalasia, providing significant improvement in obstructive

symptoms, decreased LES gradient, and improved esophageal emptying.

Limitations

The limitation of this study was the limited access to the history

of patients’ underlying disease and incomplete data on individuals’ diets and

lifestyles.

Conclusions

LHM provided satisfactory symptom

improvement in patients with advanced achalasia with promising outcomes. Also,

further investigations are required to demonstrate the most effective methods

in patients with severe achalasia.

Author contribution

MTA and MA wrote the main manuscript text and designed the

study. MSES and ASh. cooperated in data collecting and analysis.

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Relevant ethical guidelines and regulations were performed for all

experiments. This study was done

according to the Declaration of Helsinki ethical standards and consent and

agreement was obtained from all the patients and was confirmed and approved in

the surgery department.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all hospital staff and specialists for their assistance with

conforming and recording cases.

References

1. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino

JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am

J Gastroenterol. 2013 Aug;108(8):1238–49; quiz 1250.

2. Torresan F, Ioannou A,

Azzaroli F, Bazzoli F. Treatment of achalasia in the era of high-resolution

manometry. Ann Gastroenterol Q Publ Hell Soc Gastroenterol. 2015;28(3):301.

3. Vaezi MF, Felix VN,

Penagini R, Mauro A, de Moura EGH, Pu LZCT, et al. Achalasia: from diagnosis to

management. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Oct;1381(1):34–44.

4. Boeckxstaens GE.

Achalasia: virus-induced euthanasia of neurons? Vol. 103, Official journal of

the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. LWW; 2008. p. 1610–2.

5. Pandolfino JE, Fox MR,

Bredenoord AJ, Kahrilas PJ. High‐resolution manometry in clinical practice:

utilizing pressure topography to classify oesophageal motility abnormalities.

Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(8):796–806.

6. Rohof WOA, Bredenoord

AJ. Chicago Classification of Esophageal Motility Disorders: Lessons Learned.

Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017 Aug;19(8):37.

7. Hammad A, Lu VF, Dahiya

DS, Kichloo A, Tuma F. Treatment challenges of sigmoid-shaped esophagus and

severe achalasia. Ann Med Surg. 2021 Jan;61:30–4.

8. Ramzan Z, Nassri AB.

The role of Botulinum toxin injection in the management of achalasia. Curr Opin

Gastroenterol. 2013;29(4):468–73.

9. Torquati A, Richards

WO, Holzman MD, Sharp KW. Laparoscopic myotomy for achalasia: predictors of

successful outcome after 200 cases. Ann

Surg. 2006 May;243(5):583–7.

10. Yano F, Omura N, Tsuboi

K, Hoshino M, Yamamoto S, Akimoto S, et al. Learning curve for laparoscopic

Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication for

achalasia. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180515.

11. Andrási L, Paszt A,

Simonka Z, Ábrahám S, Erdős M, Rosztóczy A, et al. Surgical Treatment of

Esophageal Achalasia in the Era of Minimally Invasive Surgery. JSLS

J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2021;25(1).

12. Kashiwagi H, Omura N.

Surgical treatment for achalasia: when should it be performed, and for

which patients? Gen Thorac Cardiovasc

Surg. 2011 Jun;59(6):389–98.

13. Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino

JE. Treatments for achalasia in 2017: how to choose among them. Curr Opin

Gastroenterol. 2017;33(4):270.

14. Schlottmann F, Patti MG.

Prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications after esophageal

cancer surgery. Vol. 11, Journal of

thoracic disease. China; 2019. p. S1143–4.

15. Arain MA, Peters JH,

Tamhankar AP, Portale G, Almogy G, DeMeester SR, et al. Preoperative lower

esophageal sphincter pressure affects outcome of laparoscopic esophageal

myotomy for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(3):328–34.

16. Oelschlager BK, Chang L,

Pellegrini CA. Improved outcome after extended gastric myotomy for achalasia.

Arch Surg. 2003 May;138(5):490–7.

17. Liu J-F, Zhang J, Tian

Z-Q, Wang Q-Z, Li B-Q, Wang F-S, et al. Long-term outcome of esophageal myotomy

for achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2004 Jan;10(2):287–91.

18. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE,

Yadlapati RH, Greer KB, Kavitt RT. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Diagnosis and

Management of Achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep;115(9):1393–411.

19. Ates F, Vaezi MF. The

Pathogenesis [1] F. Ates, M.F. Vaezi, The Pathogenesis and Management of

Achalasia: Current Status and Future Directions., Gut Liver. 9 (2015) 449–463.

https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14446.and Management of Achalasia: Current Status

and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2015 Jul;9(4):449–63.

20. Siow SL, Mahendran HA,

Najmi WD, Lim SY, Hashimah AR, Voon K, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and

anterior Dor fundoplication for achalasia cardia in Malaysia: Clinical outcomes

and satisfaction from four tertiary centers. Asian J Surg [Internet].

2021;44(1):158–63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.04.007

21. Finley RJ, Clifton JC,

Stewart KC, Graham AJ, Worsley DF. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy improves

esophageal emptying and the symptoms of achalasia. Arch Surg.

2001;136(8):892–6.

22. Rice TW, McKelvey AA,

Richter JE, Baker ME, Vaezi MF, Feng J, et al. A physiologic clinical study of

achalasia: should Dor fundoplication be added to Heller myotomy? J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1593–600.

23. Kummerow Broman K,

Phillips SE, Faqih A, Kaiser J, Pierce RA, Poulose BK, et al. Heller