Psychometric

properties of the Persian version of the pain beliefs and perceptions inventory

(PBPI) in individuals with chronic low back pain

Sarvenaz Karimi-GhasemAbad 1,2,

Behnam Akhbari 3, Saeed Talebian Moghaddam 4, Ahmad

Saeedi 5

1 Razi Hospital, School of Medicine, Guilan University Medical

Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2 Physiotherapy Department of

University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3 Physiotherapy Department of University of Social Welfare and

Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4 Physiotherapy Department of Tehran

University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5 Department of Statistical Research

and Information Technology, Institute for Research and Planning in Higher

Education, Tehran, Iran

Corresponding Authors: Sarvenaz

Karimi-GhasemAbad

* Email:

s_karimi@gums.ac.ir

Abstract

Introduction: This study constitutes a methodological investigation

aimed at scrutinizing the validity and reliability of the Persian version of

the Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI) in individuals afflicted with

chronic low back pain.

Methods: To gauge reliability, both the test-retest and internal consistency

methods were deployed. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient was utilized to

assess discriminant validity among 118 individuals suffering from chronic low

back pain. The questionnaire's construct validity was ascertained by probing

the correlation between the subscales of pain persistence in the future, pain

stability in the present, self-blame, and the mysteriousness of pain, with the

constructs of pain catastrophizing, disability, pain-related anxiety, coping

strategies, quality of life, and pain intensity.

Results: Statistical analysis using the Shapiro-Wilk test revealed a non-normal

data distribution. Consequently, the non-parametric Spearman's correlation

coefficient was used to scrutinize construct and discriminant validity. The

intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) ranged from 0.58 to 0.78 for the

subscales of pain persistence in the future, pain stability in the present,

self-blame, and the mysteriousness of pain. Additionally, Cronbach's alpha

coefficient ranged from 0.74 to 0.88. With the exception of the self-blame

subscale, the other subscales exhibited significant positive correlations with

constructs of pain catastrophizing, disability, anxiety, coping strategies, and

pain intensity, as well as significant negative correlations with quality of

life (correlation coefficient ranging between 0.19 and 0.49).

Conclusion: The outcomes about test-retest reliability, construct validity, and

discriminant validity collectively suggest that the Persian version of the PBPI

possesses robust psychometric properties.

Keywords: Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory, Chronic Low Back Pain,

Validity, Reliability

Introduction

Chronic back pain is one of the most common

musculoskeletal disorders with a prevalence of 10-20%. Evidence reveals the

influential role of socio-demographic, psychological, and clinical

characteristics in the chronicity of back pain (1). Examining psychological

risk factors, in addition to the biomechanical approach, aids us in our

understanding of the persistence and spread of back pain (2).

Back pain is not always associated with movement

disorders and abnormalities. Sometimes, there is an association with negative

effects on social relationships, life satisfaction, and psychological disorders

such as depression and anxiety. The profile of psychosocial performance in

people suffering from back pain is related to their type of pain perception,

coping strategy and level of social support (3).

The biopsychosocial model of pain considers the type of

pain perception and coping strategies as two factors that can explain the

difference between individuals with chronic pain. A person’s belief toward pain

and the way they perceive it, along with their coping strategies can differ,

depending on the situation and culture (4, 5). Research suggests that

unfavorable attitudes about pain have an impact on how well chronic pain is

treated. Unfavorable attitudes can also turn acute pain into chronic pain and have

a detrimental effect on a patient's overall health, self-efficacy, and

performance (5, 6). It is recommended that individuals with chronic pain use a

variety of cognitive-behavioral techniques to address maladaptive beliefs (6).

Different tools were designed to evaluate and determine the beliefs related to

pain. The Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI) is one of them. Quick

and easy identification of cognitive factors is one of the reasons for choosing

this scale. This 16-item instrument was designed by Williams and Thorn in 1989.

Each of its statements is rated, using a 4-point Likert scale including options

of strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree (7). The PBPI evaluates

emotions, behavior, and pain-related perceptions. Strong relationships have

been found between this tool and personality traits, physiological processes,

coping mechanisms, and feelings of anxiety, depression, and pain (8).

The original version of the questionnaire is

composed of three factors namely, time (belief in the stability and continuity

of pain), mysteriousness (belief in the mysteriousness and unknowingness of

pain) and self-blame (self-guilt and blaming oneself for the pain). The study

found that the internal consistency coefficients for the time and

mysteriousness of pain subscales as well as self-blame were 0.65 and 0.80,

respectively (7). According to a study by Turner et al. (2000) on patients with

chronic pain, those who believe in persistence of their pain in the present and

continuation of it in the future are more likely to experience physical

disability and depression with more severity. The lack of repetition of the

time factor, and the emergence of two factors of belief in pain permanence and

pain constancy led to the design of a four-factor model (9). Asghari et al.

(2005) investigated the psychometric properties of this questionnaire among 232

patients with cancer pain. In this study, the construct validity of the

questionnaire was tested using the factor analysis method, and the fourth

statement (pain confuses me) was removed from the factor analysis due to a very

strong positive bias (10).

The first factor is belief in Pain Permanence with a

score between 8 and -8. A positive score indicates a deeper belief in the

continuation of pain in the future. The second factor is self-blame. Its score

is between 6 and -6, with a positive score suggesting a deeper belief in

self-blame. Pain Constancy is stated as the third factor. Its score ranges from

8 to -8. A positive score in this situation expresses a deeper belief in the

stability of pain. The fourth and final factor is Mysteriousness, scoring between

8 and -8. A higher score shows a deeper belief in the unknowability of pain and

a person's attitude towards pain as an ambiguous phenomenon. The internal

consistency coefficients of these four factors varied between 0.70 and 0.77.

Persian version of PBPI questionnaire has a significant correlation with

disability, psychological structures and coping strategies (10).

The PBPI questionnaire has been translated into several

languages with different target populations (6, 11-15). Although the Persian

version of this questionnaire is available, due to the different nature of

chronic cancer pain and chronic musculoskeletal pain, the psychometric

characteristics of the Persian version have not been investigated among people

with chronic low back pain. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to

investigate the validity and reliability of the Persian version of PBPI among

this group of patients. Based on the COSMIN checklist, the following hypotheses

were considered to express the correlation between the PBPI questionnaire and

other scales (16).

1. There is a positive and significant correlation

between the subscales of the PBPI questionnaire and the constructs of pain

catastrophizing, Roland Morris disability questionnaire, coping mechanisms,

pain-related anxiety symptoms and pain intensity of people dealing with chronic

back pain.

2. There is a negative and significant correlation

between the subscales of the PBPI questionnaire and the quality of life of

people with chronic back pain.

Methods

This study of localization, validity and reliability of

PBPI scales is a methodological one. 118 people suffering from chronic back

pain who visited the physical therapy centers of Tehran in the summer and fall

of 2017 and 2018 participated in this study (15). The criteria for entering the

study include: suffering from back pain for more than three months, the ability

to speak Farsi (Persian language), and being in the age range of 18 to 55 (17).

People with cognitive disorders, known pathologies (such as discopathy, spinal

canal stenosis, fractures in the spine and osteoporosis), and spondylolisthesis

as well as those who were pregnant were excluded from the study (17).

Eventually, 118 people were eligible to participate in the study and all of

them signed the participation consent form. This study was approved by the

Ethics Committee of The University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation

Sciences (No:IR.USWR.REC.1396.205).

Pain Beliefs

Perception Inventory (PBPI)

The questionnaire was designed by Williams and colleagues

in 1989 to assess people with chronic non-cancer pain. The original version of

this questionnaire has 16 items and three subscales including mystery, time,

and self-blame. Patients rate their pain beliefs on a four-point Likert scale

from -2 (completely disagree) to +2 (completely agree). The scoring of 3, 9, 12

and 15th items are calculated in reverse (7). After the factorial structure of

the PBPI was examined, four factors (mystery, permanence, constancy, and

self-blame) were ultimately identified (9).

Asghari et al. localized this questionnaire in Persian language in 2005,

which resulted in 15 items with four similar subscales (10). The factor of

belief in pain permanence in the future is obtained through summation of the

scores achieved from statements Nos. 4, 8, 11 and 14. Summing up the scores of

statements Nos. 6, 10 and 12 presents us with the factor of belief in

self-blame. Moreover, the score from statements Nos. 5, 3, 9 and 15, states the

factor of belief in the constancy of pain in the present time. The factor of

belief in the mystery of pain is obtained from the sum of the scores related to

statements Nos. 2, 1, 7 and 13.

Coping

Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ-8)

The CSQ questionnaire was designed by Rosenstiel and

Keefe (1983) in people with chronic back pain. This tool had 50 items, 7

diverse cognitive and behavioral strategies. The six mentioned cognitive

strategies include diverting attention, catastrophizing, ignoring pain

sensations, reinterpretation, coping self-statements, and praying. It is

considered a behavioral coping strategy to increase the level of activity.

Behavioral and cognitive coping strategy scales of each item have seven options

(0 = never use, 3 = sometimes use, 6 = always use) (18). Each scale is scored

between 0 and 36. The Persian version of this scale is available, which,

similar to the original version, has Cronbach's alpha coefficient of above 0.70

for subscales (19).

Roland Morris

Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)

This questionnaire is used to measure the disability

caused by chronic back pain. It contains 24 questions with yes and no answers.

Its score is from 0 to 24, where 0 indicates no disability and 24 indicates

severe disability. This scale is widely used in various researches and has

favorable internal consistency and construct validity (20).

Visual Analog

Scale (VAS)

Visual analog scale is used to measure pain intensity.

This scale includes a straight horizontal line of 100 mm, with one end being

"no pain" and the other being "the most severe pain

possible". The patient marks the pain intensity on the 100 mm continuum of

this straight line (21).

Pain

Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)

The scale of pain catastrophizing was designed by

Sullivan (1995) with the aim of evaluating the level of catastrophic thoughts

and behaviors of a person (22). In this questionnaire, subjects are asked to

reflect on past painful experiences. Then, rate the degree they experience the

thirteen mentioned thoughts and feelings during these events on a 6-point

scale. The scale ranges from 0, "not at all or at all" to 4,

"always or always" (23).

Beck Depression

Inventory-II (BDI-II)

This questionnaire was first designed by Beck. Today, its

21-item version is used which includes specific symptoms of depression. The

samples are selected with one of these items that indicates the severity of

depression symptoms (24). Each item has a score between 0 and 3. The total

score is between 0 and 63. This questionnaire can be used in people over 13

years old and it was localized by Ghasemzadeh in 2005. Its Cronbach's alpha was

reported as 0.87 (25).

Pain Anxiety

Symptom Scale (PASS-20)

Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale is a self-report tool designed

by McCracken in 1992. It is deployed to assess anxiety and fear reactions

caused by pain in people who suffer from chronic pain. The total score is

between 0 and 100. A higher score indicates pain-related anxiety (26).

Shanbezadeh et al (2017) scrutinized the validity and reliability of this tool

among the chronic back pain group. Intraclass correlation coefficients for all

subscales were higher than 0.70%. Also, Cronbach's alpha was more than 0.70% for

all the subscales (27).

Short Form-36

(SF-36)

The quality-of-life scale, a shortened 36-itemed form,

was designed by Ware (1992) to evaluate the quality of life and general health

(28). This questionnaire was translated into Farsi in 2005 and its psychometric

properties were examined (29).

Statistical

Analysis

Ceiling and floor effects determine the number and

percentage of people who got the lowest and highest score in each of the

subscales. If more than 15% of patients have a minimum or maximum score, the

questionnaire cannot differentiate between patients at the extremes of the

scale (30) .

To evaluate the reliability, this scale was given to 54

patients with chronic back pain in two stages, with a time interval of one

week. The purpose of retest assessments was to differentiate between actual

score variance and temporary error, which arises from time-related variations

in individuals' emotional states, physiological conditions, or cognitive

processes (31). In order to measure relative and absolute reliability,

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), Standard error of measurement (SEM) and

Minimal detectable change (MDC) were calculated between the two stages of

measurement (32). By using absolute reliability indices, it is possible to

distinguish clinical changes in the sample's condition from changes that may be

due to measurement error. To calculate ICC in SPSS version 17, Two-Way

Random-Effects Model or (1 and 2) was used.

ICC equal to or higher than 0.7 was considered as the

acceptable limit of the reliability level. SEM was obtained using ICC and

standard deviation, and MDC was obtained using SEM, with its calculation

formula stated as below (33):

![]()

![]()

Internal consistency reliability was assessed with

Cronbach’s Alpha on the 4 subscales of the PBPI, which is used to evaluate the

strength of the relationship between individual's questions within the scale.

Mean scores, an alpha coefficient of more than 0.80 was considered as sufficient

and acceptable (32).

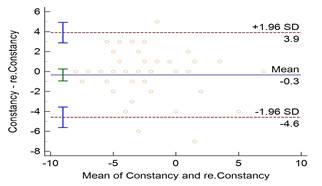

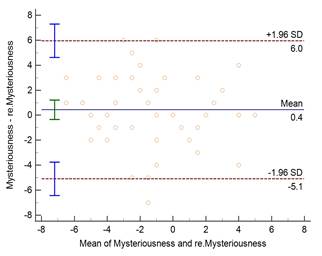

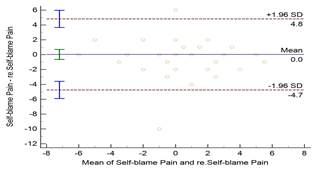

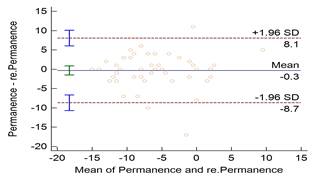

The Bland-Altman analysis was used to assess how well

subscales agree between tests and retests. The mean difference and limits of

agreement with a 95% confidence interval served as the method's outcome

measures (17).

To evaluate the construct validity of the Persian version

of the PBPI scale, the correlation between the score of their subscales and the

scores of the Persian version of RDMQ, PCS, CSQ, CSQ, PASS-20, SF-36 and pain

intensity was calculated in people with non-specific chronic back pain.

In order to calculate the Item-Total correlation,

Dimensionality on an item level, after individually removing the score of each

item from the subscale score related to it, Spearman's correlation coefficient

was measured for each item with its corresponding subscale score. Acceptable

correlation coefficients are 0.4 or lower, and each item's correlation with

each of the other subscales should be less than that of the relevant subscale

(34).

Results

The background information of people was collected

through a self-report questionnaire designed by the researcher. The average age

of the subjects was 36.36 with a standard deviation of 10.51 years. The average

pain intensity during the test was 30.9 mm based on the linear scale. 29.2% of

the subjects in this research were men and 70.8% were women. 19.1% of subjects

had education up to diploma, 48.4% had bachelor's degree and 32.5% had master's

and doctorate education. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk statistical test

showed that the distribution of data in all subscales of the PBPI questionnaire

was not normal. Therefore, in the present study, non-parametric statistical

methods were used to check the correlation of data.

Table 1 shows the floor and ceiling effect for the

subscales’ scores of the Persian version of PBPI. As can be seen in the table,

less than 15% of people had the minimum or maximum scores of the subscales,

except the self-blame subscale.

The obtained results from ICC, SEM, MDC and Bland-Altman

agreement along with the mean and standard deviation of each subscale are also

mentioned in Table 1. Munro's classification was used to describe the degree of

relative reliability (17).

Reliability between zero and 0.25 was considered very

low, 0.26 and 0.49 low, 0.50 and 0.69 medium, 0.7 and 0.89 high, and finally,

0.9 and 1 very high. For the majority of the subscales, ICC values between 0.70

and 0.78 were found, which is above the acceptable limit. However, for the

subscale of belief in the mystery of pain, an average score of 0.58 was

reported. According to Table 1, Cronbach's alpha values in this study for the

subscales’ scores ranged from 0.74 to 0.88.

Table

1. Flooring

and ceil effects, Test-retest reliability, limitation of agreement of Persian

version of PBPI (n=118).

|

SUBSCALE |

Permanence |

Self-blame Pain |

Constancy |

Mysteriousness |

|

mean |

-6.23 |

0.26 |

-2.85 |

-1.25 |

|

SD |

5.58 |

3.13 |

3.2 |

3.02 |

|

Cronbach’s

alpha |

0.82 |

0.83 |

0.88 |

0.74 |

|

ICC |

0.70(0.53-0.81) |

0.72(0.56-0.83) |

0.78(0.65-0.9087) |

0.58(0.38-0.73) |

|

SEM |

3.05 |

1.65 |

1.5 |

1.95 |

|

MMDC |

8.47 |

4.59 |

4.16 |

5.42 |

|

flooring

effect % |

0.80% |

3.40% |

1.70% |

3.40% |

|

ceiling

effect% |

2.50% |

28% |

4.20% |

1.70% |

|

mean

difference (95% CI) |

-0.301 (-1.47-0.87) |

0.37 (-0.635-0.71) |

-0.339 (-0.93-0.25) |

0.43 (-0.34-1.21) |

|

LOA |

-8.67-8.07 |

-4.74-4.82 |

-4.58-3.9 |

-5.08-5.95 |

SD: standard deviation, ICC: intraclass correlation

coefficient, SEM: Standard Error of Measurement, MDC: minimal detectable

change, LOA: limitation of agreement.

Figure

1.

Bland-Altman Plot of constancy subscale of Persian version of PBPI in

individual with non-specific Chronic Low Back pain.

Figure

2. Bland-Altman

Plot of Mysteriousness subscale of Persian version of PBPI in individual with

non-specific Chronic Low Back pain.

Figure

3. Bland-Altman

Plot of self-blame subscale of Persian version of PBPI in individual with

non-specific Chronic Low Back pain.

Figure

4. Bland-Altman

Plot of Permanence subscale of Persian version of PBPI in individual with non-specific

Chronic Low Back pain.

The correlation coefficients between the subscales’

scores of the PBPI questionnaire with the scores of the RMDQ, CSQ, PCS,

PASS-20, SF-36 and pain intensity are summarized in table 2.

Table

2. Correlation

coefficients between PBPI questionnaire scores with RMDQ, CSQ, BDI-II, PCS,

PASS-20, SF-36 questionnaire scores and pain intensity (n=118).

|

Scales/ subscales |

Permanence |

Self-blame Pain |

Constancy |

Mysteriousness |

|

PCS |

0.424** |

0.139 |

0 .361** |

0.332** |

|

PASS.20 |

0.353** |

0.110 |

00.266** |

0.230* |

|

BDI-II |

0.416** |

0.073 |

0 .367** |

0.266** |

|

SF36.PH.T |

-0.511** |

-0.021 |

-0.500** |

-0.306** |

|

SF36.MH.T |

-0.323** |

-0.069 |

-0.237* |

-0.269** |

|

SF36.T |

-0.455** |

-0.050 |

-0.401** |

-0.315** |

|

Diverting

attention |

-0.027 |

0.076 |

0.031 |

-0.102 |

|

Reinterpretation |

0.025 |

.192* |

0.054 |

-0.006 |

|

Catastrophizing |

.500** |

0.150 |

0.398** |

0.300** |

|

Ignoring

pain |

-0.198* |

0.137 |

-0.118 |

-0.061 |

|

Praying-hope |

0.110 |

0.075 |

0.154 |

-0.007 |

|

self-statement |

-0.074 |

0.141 |

0.050 |

-0.167 |

|

Increasing

activity levels |

0.023 |

0.182 |

0.093 |

0.088 |

|

VAS. |

0.212* |

0.147 |

0.194 |

0.062 |

|

RMDQ |

0.462** |

0.172 |

0.482** |

0.190* |

**

Correlation coefficients significant at P<0.000, *Correlation coefficients

significant at P<0.05. PCS; Pain Catastrophizing Scale, VAS; Visual Analogue

Scale, RMDQ; Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire; BDI-II; Back Inventory

Index, SF-36; Short Form, MH; Mental Health, PH; Physical Health, PASS; Pain

Anxiety Symptom Scale, Pain Intensity.

The results of Table 3 shows that the Spearman

correlation between each item and its corresponding subscale was between 0.360

and 0.689, whereas the correlation with other subscales was between 0.089 and

0.589. This means that the correlation of each item with its own subscale was

more than the correlation between the score of that item with other subscales.

A significant value for the correlation between all items and subscales was

reported to be less than 0.001.

Table

3. Item-total

correlation of Persian version of PBPI (n=118).

|

Item |

Permanence |

Self-blame Pain |

Constancy |

Mysteriousness |

|

I4 |

0.689** |

0.259** |

0.616** |

0.399** |

|

I8 |

0.399** |

0.019 |

0.311** |

0.143** |

|

I11 |

0.454** |

0.002 |

0.326** |

0.377** |

|

I14 |

0.461** |

0.072 |

0.333* |

0.243* |

|

I6 |

0.12 |

0.684** |

0.123 |

0.038 |

|

I10 |

0.057 |

0.658** |

0.027 |

-0.009 |

|

I12 |

0.213* |

0.36** |

0.123 |

0.116 |

|

I3 |

0.608** |

0.037 |

0.578** |

0.207* |

|

I5 |

0.654** |

0.035 |

0.584** |

0.256** |

|

I9 |

0.701** |

0.015 |

0.602** |

0.248** |

|

I15 |

0.667** |

0.059 |

0.478** |

0.357** |

|

I1 |

0.037 |

0.197* |

0.801** |

0.551** |

|

I2 |

0.061 |

0.333** |

0.654** |

0.636** |

|

I7 |

0.081 |

0.289** |

0.744** |

0.512** |

|

I13 |

-0.131 |

0.186 |

0.677** |

0.486** |

Discussion

In the current study, less than 15% of the participants

met the minimum and maximum scores in the subscales, with the exception of

self-blame, which had a floor impact of 0.28%. This can show the power of the

Persian version of the PBPI scale in differentiating the various beliefs and

pain perception in patients with back pain. Findings from the current study

corroborated results from a research by Monticone et al. (2014) and Azevedo et

al. (2017), where more than 15% of individuals had at least a minimal score on

the self-blame subscale. (6, 15).

All subscales' ICC values fell between 0.7 and 0.78, with

the exception of the mystery of pain subscale, which had a score of 0.58. This

result validates the average of the mystery of pain subscale and the other

three subscales' strong reliability. It also shows that in both tests, the

order of people with respect to the entire test group has stayed appropriate.

The results of another study including individuals with chronic pain fell

within a same range (0.88-0.79) (15). The results of the other research, which

included participants with chronic back pain, were similar (6). Cronbach's

alpha coefficient of the subscales of mystery of pain was reported to be in the

range of 0.74 to 0.88, which is in line with the results of other studies that

had been done previously (6, 10, 15).

The minimum MDC for the subscales of belief in pain

permanence, self-blame, pain constancy, and mysteriousness were 89.47,4.59,

4.16, and 5.42, respectively. With the aid of the MDC results, therapists and

researchers are able to ascertain the true changes and validity of the

subscales' scores (27). The agreement between the mean difference and the

results indicates that each subscale fell within the predetermined limitations.

Failure to calculate MDC and SEM and agreement in previous studies has limited

the possibility of comparing their results.

The PBPI subscales' construct validity results suggested

that, all subscales, except self-blame exhibited a positive and significant

association with disability, pain-related anxiety symptoms, depression, and

catastrophizing. Also, a significant negative relationship was observed between

the quality of life and the subscales of pain permanence, pain constancy, and

pain mystery. Among the coping strategies, only catastrophizing showed a

positive and significant relationship with three subscales of the PBPI questionnaire,

except self-blame. A positive and significant relationship was reported between

pain intensity and the subscales of pain

among 122 people with chronic pain. A negative

relationship was observed between the level of quality of life and the

subscales of pain mystery, pain constancy, and pain permanence. Similar to the

present study, they did not report a significant relationship between this

questionnaire and the subscale of self-blame (15).

A notable positive correlation was observed between the

permanence subscales and pain intensity, while no such association was

identified for the remaining subscales. The permanence subscales of the PBPI

concentrate on the daily life encounters of pain, suggesting a potentially more

robust connection with the factual experience of pain intensity as assessed

through the VAS. Contrary findings were reported by Blanch et al., who

evidenced a strong correlation between all PBPI subscales and pain intensity.

Discrepancies in results may be attributed to variations in sample sizes;

notably, the study by Blanch et al. predominantly involved participants

afflicted with fibromyalgia (8).

According to the Cognitive-Behavioral Theory and the

Biopsychosocial model, there is a significant correlation between disability,

pain catastrophizing, and predictable coping strategies (8). This statement

confirms the results of previous studies as well as the present one. The lack

of correlation between self-blame and other scales was also found in previous

studies. This could be due to the lack of a structure related to self-blame,

which calls for more attention in future studies (1, 13, 35, 36). The construct

validity results confirmed the hypotheses considered at the beginning of the

present research.

The strong correlation between the items of the Persian

version of PBPI with their corresponding subscale indicates the appropriate

structure of this version. In addition, it shows that each subscale consists of

appropriate items (6, 15).

Limitation

This

study's limited number of participants may compromise its external validity and

generalizability. Moreover, lack of implementation of content validity and

exploratory factor analysis is another limitation that can be addressed in

future studies.

Conclusion

The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the

Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI) were examined among individuals

suffering from chronic back pain, demonstrating commendable levels of validity

and reliability. This instrument can be effectively employed by physical

Therapists and researchers to assess patients' beliefs and perceptions

regarding pain, contributing to enhanced treatment outcomes.

Competing

interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Statement

of the Institutional Review Board Approval

Informed

consent form approved by the Ethics Committee at University of Social Welfare

& Rehabilitation Sciences (No: IR.USWR.REC.1396.205).

Authors

contributions

BA, STM and

AS contributed to the concept and design of the study and collected the

data. SKGA drafted the manuscript and prepared the final version, read

and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Finally, all authors approved the final version of the manuscript for

publication.

References

1. Müller M,

Curatolo M, Limacher A, Neziri AY, Treichel F, Battaglia M, et al. Predicting

transition from acute to chronic low back pain with quantitative sensory

tests—A prospective cohort study in the primary care setting. European journal

of pain. 2019;23(5):894-907.

2. Gajsar H,

Titze C, Levenig C, Kellmann M, Heidari J, Kleinert J, et al. Psychological

pain responses in athletes and non‐athletes with low back pain: avoidance and

endurance matter. European Journal of Pain. 2019.

3. Misterska E,

Jankowski R, Glowacki M. Chronic pain coping styles in patients with herniated

lumbar discs and coexisting spondylotic changes treated surgically: Considering

clinical pain characteristics, degenerative changes, disability, mood

disturbances, and beliefs about pain control. Medical science monitor :

international medical journal of experimental and clinical research.

2013;19:1211-20.

4. Ferreira-Valente

MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Psychometric properties of the portuguese

version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. Acta reumatologica portuguesa.

2011;36(3):260-7.

5. Tabriz ER,

Mohammadi R, Roshandel GR, Talebi R. Pain Beliefs and Perceptions and Their

Relationship with Coping Strategies, Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in

Patients with Cancer. Indian journal of palliative care. 2019;25(1):61-5.

6. Monticone M,

Ferrante S, Ferrari S, Foti C, Mugnai R, Pillastrini P, et al. The Italian

version of the Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory: cross-cultural

adaptation, factor analysis, reliability and validity. Quality of life research

: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and

rehabilitation. 2014;23(6):1789-95.

7. Williams DA,

Thorn BE. An empirical assessment of pain beliefs. Pain. 1989;36(3):351-8.

8. Blanch A,

Solé S. Classification of pain intensity with the pain beliefs and perceptions

inventory (PBPI) and the pain catastrophizing scales (PCS). Quality of life

research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment,

care and rehabilitation. 2023;32(10):2853-9.

9. Turner JA,

Jensen MP, Romano JM. Do beliefs, coping, and catastrophizing independently

predict functioning in patients with chronic pain? Pain. 2000;85(1-2):115-25.

10. Asghari

Moghadam MA KN, Amarloo P. The role of beliefs about pain in adjustment to

cancer. Daneshvar Raftar. 2005(13):1-22.

11. Dysvik E,

Lindstrøm TC, Eikeland O-J, Natvig GK. Health-related quality of life and pain

beliefs among people suffering from chronic pain. Pain management nursing.

2004;5(2):66-74.

12. Williams DA,

Keefe FJ. Pain beliefs and the use of cognitive-behavioral coping strategies.

Pain. 1991;46(2):185-90.

13. Herda CA,

Siegeris K, Basler H-D. The Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory: further

evidence for a 4-factor structure. Pain. 1994;57(1):85-90.

14. Wong WS,

Williams DA, Mak KH, Fielding R. Assessing attitudes toward and beliefs about

pain among Chinese patients with chronic pain: Validity and reliability of the

Chinese version of the Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (ChPBPI). Journal

of pain and symptom management. 2011;42(2):308-18.

15. Azevedo LF,

Sampaio R, Camila Dias C, Romão J, Lemos L, Agualusa L, et al. Portuguese

Version of the Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory: A Multicenter Validation

Study. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain.

2017;17(6):808-19.

16. Mokkink LB,

Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN

checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement

properties: a clarification of its content. BMC medical research methodology.

2010;10(1):1-8.

17. Karimi-GhasemAbad

S, Akhbari B, Saeedi A, Moghaddam ST, Ansari NN. The Persian Brief Illness

Perception Questionnaire: validation in patients with chronic non-specific low

back pain. 2020.

18. Rosenstiel AK,

Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients:

Relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain.

1983;17(1):33-44.

19. Asghari A,

Golak N. The roles of pain coping strategies in adjustment to chronic pain.

Scientific Information Database (SID). 2005.

20. Mousavi SJ,

Parnianpour M, Mehdian H, Montazeri A, Mobini B. The Oswestry disability index,

the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, and the Quebec back pain disability

scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine.

2006;31(14):E454-E9.

21. Price DD,

McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as

ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17(1):45-56.

22. Sullivan MJ,

Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation.

Psychological assessment. 1995;7(4):524.

23. Raeissadat S,

Sadeghi S, Montazeri A. Validation of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) in

Iran. J Basic Appl Sci Res. 2013;3:376-80.

24. Beck AT, Steer

RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio. 1996;78(2):490-8.

25. Ghassemzadeh

H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a

Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory--Second edition:

BDI-II-PERSIAN. Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA).

2005;21(4):185-92.

26. McCracken LM,

Dhingra L. A short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20):

preliminary development and validity. Pain Research and Management.

2002;7(1):45-50.

27. Shanbehzadeh

S, Salavati M, Tavahomi M, Khatibi A, Moghadam ST, Khademi-kalantari K.

Reliability and Validity of the Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale in Persian Speaking

Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Spine. 2017.

28. Ware J, John

E, Gandek B. The SF-36 Health Survey: Development and use in mental health

research and the IQOLA Project. International Journal of Mental Health.

1994;23(2):49-73.

29. Montazeri A,

Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36):

translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of life

research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment,

care and rehabilitation. 2005;14(3):875-82.

30. Seydi M,

Akhbari B, Abad SKG, Jaberzadeh S, Saeedi A, Ashrafi A, Shakoorianfard MA.

Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the brief illness

questionnaire in Iranian with non-specific chronic neck pain. Journal of

Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2021;28:323-31.

31. Polit DF, Yang

F. Measurement and the measurement of change: a primer for the health

professions: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015.

32. Terwee CB, Bot

SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria

were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires.

Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2007;60(1):34-42.

33. Seydi M,

Akhbari B, Abdollahi I, Abad SKG, Biglarian A. Confirmatory factor Analysis,

reliability, and validity of the Persian version of the coping strategies

questionnaire for Iranian people with nonspecific chronic neck pain. Journal of

Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2021;44(1):72-84.

34. Howard KI,

Forehand GA. A method for correcting item-total correlations for the effect of

relevant item inclusion. Educational and Psychological Measurement.

1962;22(4):731-5.

35. Morley S,

Wilkinson L. The Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory: a British replication.

Pain. 1995;61(3):427-33.

36. Strong J,

Ashton R, Stewart A. Chronic low back pain: toward an integrated psychosocial

assessment model. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology.

1994;62(5):1058.