A rare case of bronchial glomus tumour

of uncertain malignant potential

Sharanya

Sathish 1, Shanthi Velusamy 2 *, Divya Vijayanarasimha 2,

Arjun S Kashyap 1, Sanjeev Kulkarni 3

1 Sri Shankara Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Bengaluru, India

2 Department of Pathology, Sri Shankara Cancer Hospital and Research

Centre, Bengaluru, India

3 Department of Surgical Oncology, Sri Shankara Cancer Hospital and

Research Centre, Bengaluru, India

Corresponding

Authors: Shanthi Velusamy

* Email: shanz84@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Glomus tumours are typically benign pericytic

mesenchymal neoplasms, occurring in the soft tissues of distal extremities, and

rarely seen in deep soft tissues and visceral locations. Malignant glomus

tumours are exceedingly uncommon. Here, we present a rare case of glomus tumour

with uncertain malignant potential, arising in the bronchus of a young female

patient. This case report highlights the clinical, radiological, and

pathological aspects of this unusual entity, discussing the challenges in

diagnosis and management and reviewing relevant literature on its behaviour and

treatment options.

Case Presentation: A 35-year-old lady with

progressive breathlessness and cough, was found to have an obstructive mass

lesion in the right upper lobe bronchus on CT scan. Check bronchoscopy and

biopsy revealed features of a low-grade spindle cell lesion, with the possible

differentials of a Glomus tumour and low-grade myofibroblastic tumour. She

underwent right upper lobectomy; the final histopathological exam with the aid

of immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of a Glomus tumour of uncertain

malignant potential. Post-operatively, due to localised disease with negative

surgical margins, she was kept on regular follow-up and was asymptomatic 6

months post-surgery.

Discussion: The possibility of a Glomus tumour must be considered for tumours with

plump spindle to round cell morphology on a bronchoscopic biopsy.

Immunohistochemistry helps to exclude most differentials. The assessment of

malignant potential in Glomus tumour requires thorough examination of a

completely resected tumour sample. Molecular studies have shown NOTCH1 gene

rearrangements in both benign and malignant Glomus tumours. However, it does

not help to predict malignant potential in benign-appearing tumours.

Conclusion: Bronchial Glomus tumours of uncertain malignant potential are rare

tumours requiring more research on molecular markers for prognostication and

treatment. This case is presented for its rarity, diagnostic and prognostic

challenges.

Keywords: Glomangiomyoma, Coin lesion, Glomus Tumour of Uncertain Malignant

Potential, SMA, Glomus classification

Introduction

Glomus tumours (GT) originate from the glomus cells of

the glomus body, a neuro-myo-arterial structure involved in regulating

cutaneous circulation. These tumours constitute less than 2% of soft tissue

tumours (1) and usually arise in distal extremities. Rare sites of

occurrence include the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary system,

mediastinum, nerves, bones, and lungs (2). When arising in the bronchopulmonary tract, a number of entities enter

the differential diagnosis and the possibility of glomus tumour may not be

suspected, due to its rarity. The differentials considered in this site usually

include carcinoid tumour, solitary fibrous tumour, sclerosing haemangioma,

leiomyoma, paraganglioma etc. Though surgery remains the primary modality

of treatment for most of these tumours, the prognosis, behaviour and adjuvant

treatments vary and therein lies the importance of accurate diagnosis. Glomus

tumours have been conventionally classified as benign, ‘of uncertain malignant

potential’ and malignant. The assessment of malignant potential of GT is

challenging on small bronchoscopic biopsies as they may not represent the

entire picture. This is especially important for malignant Glomus tumours, as

they behave very aggressively. This case report discusses a rare case of a

young female with an endobronchial glomangiomyoma of uncertain malignant

potential. The clinical and diagnostic work-up, treatment given and relevant

published literature are discussed.

Case

presentation

A 35-year-old lady presented

with progressively worsening intermittent cough and breathlessness on exertion

over a period of 1 month. She did not have fever, loss of appetite, weight

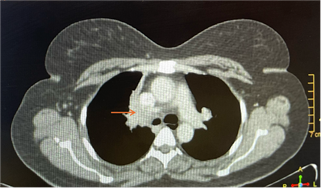

loss, or pain. Her medical history was unremarkable. A chest CT scan (Figure 1)

revealed an exo-endoluminal mass lesion occluding the right main stem bronchus;

the endoluminal component appeared hypodense and exoluminal component appeared

hyperdense with intrabronchial extension at places. Check bronchoscopy

confirmed a mass lesion in the right main bronchus causing near-complete

occlusion. Tumour debulking was performed in view of obstruction, using

electrocautery snare under general anaesthesia. Cryo-debulking was also

performed. The tumour was noted to be arising from the right upper lobe

bronchus with the rest of the right bronchial tree being normal. Argon plasma

coagulation was used to control bleeding after debulking. The biopsy sample was

subjected to histopathological evaluation and immunohistochemistry. At this

point of time, the provisional clinical diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumour was

considered.

Figure 1. CT thorax

showing right bronchial hypodense endoluminal mass (arrow).

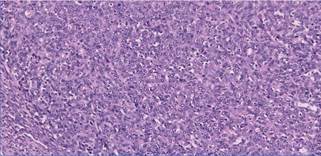

Histologically, the biopsy

showed a neoplasm composed of spindle to oval cells with pale eosinophilic

cytoplasm and plump ovoid to spindle nuclei, arranged in sheets and fascicles.

There was no significant nuclear atypia; mitotic figures were sparse (less than

1 per 2 square mm). Thin-walled branching blood vessels were present without evidence

of calcifications or necrosis. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated strong

tumour positivity for Vimentin, alpha-SMA (Smooth Muscle Actin), focal S100

positivity, and a Ki67 index of ~12% at hotspots. Negative stains included

PanCK (excluding a salivary neoplasm), neuroendocrine markers -Synaptophysin

& Chromogranin (excluding carcinoid), STAT6 (excluding solitary fibrous

tumour), Desmin (excluding leiomyoma), TLE1 (excluding synovial sarcoma) and

ALK (for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour). A brisk inflammatory activity

characteristic for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) was not evident in

the limited sampling. The differentials considered at this stage were a Glomus

tumour and a low-grade myofibroblastic tumour, in view of spindled morphology,

SMA positivity and relatively low Ki67 index. The final diagnosis was reserved

for the resection specimen to evaluate other areas of the tumour.

A PET-CT scan confirmed

localized disease with low grade FDG uptake (SUV max 3.5). In view of features

suspicious for a localised neoplastic pathology of uncertain malignant

potential, the patient subsequently underwent right upper lobectomy. The

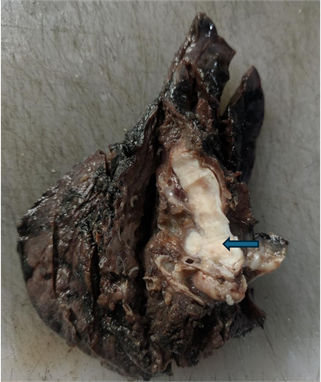

resected specimen (Figure 2) showed a solid, grey-white endobronchial tumour

involving the largest and another branching bronchus, measuring 3.5x1.5x1.5 cm.

Figure 2. Lobectomy

specimen with cross section of main bronchus displaying grey-white tumour

filling the lumen (arrow).

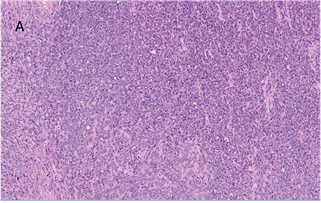

The microscopic examination

revealed a tumour composed of oval to spindle cells arranged in sheets with

interspersed thin-walled blood vessels and separated by focal hyalinized stroma

(Figure 3A). A few areas resembling smooth muscle fibres in fascicles were also

observed (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. A. Microscopic

examination shows sheets of spindled cells with scant hyalinised matrix

(H&E, 100X). B. Smooth muscle component seen at places within the tumour

(arrow) (H&E, 40X).

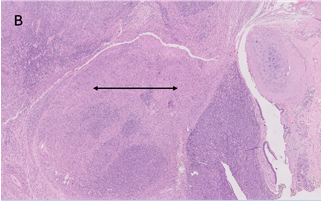

The tumour cells exhibited

scant cytoplasm, elongated spindled to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin,

occasional intranuclear grooves, and inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Microscopic

examination-high power magnification shows spindled tumour cells with plump

spindle to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli.

(H&E, 400X).

Some areas showed moderate

nuclear atypia. The mitotic rate was 3 per 2 sq. mm. Lymphovascular and

perineural invasion were not identified. Seven perihilar lymph nodes showed

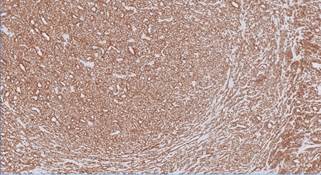

reactive hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tumour showed

similar findings as seen in the bronchoscopic biopsy, including strong

positivity for vimentin and SMA (Figure 5). h-Caldesmon was positive only in

the myomatous component and negative in other areas. There was no inflammatory

component to suggest inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT).

Figure 5. Diffuse strong

cytoplasmic staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) seen in tumour cells by

IHC.

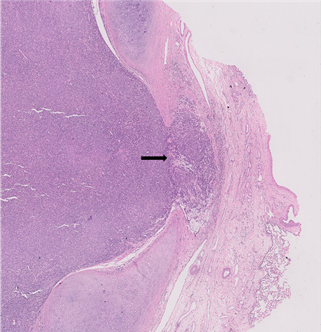

The characteristic

perivascular concentric arrangement of tumour cells seen in myopericytoma and

biphasic zonation phenomenon (central spindle cells with hemangiopericytomatous

pattern and peripheral hyalinised area) of a myofibroma were not seen; both conditions

are generally seen in dermis and subcutis and very rarely in deep locations.

The complete histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of the tumour

showed morphology consistent with a Glomangiomyoma. Invasion into the bronchial

wall and peribronchial fibrous tissue was observed focally (Figure 6). There

was no evidence of marked nuclear atypia or atypical mitosis to indicate

malignancy. Applying WHO classification of Glomus tumours (2), due to focal

moderate nuclear atypia, infiltration of the bronchial wall, deep location, and

size exceeding 2 cm, the diagnosis of Glomus tumour (Glomangiomyoma) of

uncertain malignant potential (GTUMP) was made. In view of negative surgical

margins and absence of metastatic disease, the patient was placed on close

follow-up and remained asymptomatic at 6 months post-surgery.

Figure 6. Tumour

infiltrates bronchial wall microscopically (arrow).

Discussion

The term "glomus" originates from Latin,

meaning "ball" or spherical mass. Oide et al. analysed

reported cases of bronchopulmonary Glomus tumours, identifying 36 cases arising

from either the bronchus or lung; this series showed that the tumour occurred

predominantly in adult males (3). A PubMed search for "Glomus tumour of

uncertain malignant potential" and "bronchopulmonary Glomus

tumours" yielded two additional case reports (4), (5) and a series of 11

cases (6) from 2010 to 2019.

Radiologically, GT present as variable-sized lesions

on chest radiographs. Cunningham JD et al (7) reviewed imaging

findings in 21 cases, noting that both benign and malignant tumours appear as well-circumscribed

solid masses without internal calcification or cavitation. On CT, tumours

exhibit peripheral vascularity with heterogeneous peripheral contrast

enhancement and a lack of central enhancement in both benign and malignant

lesions. PET-CT is of limited use in differentiating benign from malignant

primary lesions, as both may show absent or low-to-moderate FDG uptake.

One of the primary challenges in evaluating Glomus

tumours is assessing their malignant potential. The recent WHO classification

(2) categorizes Glomus tumours into benign, GTUMP, and malignant based on

atypical features: Benign tumours show classic histology and lack atypical

features; malignant tumours show marked nuclear atypia or atypical mitosis;

GTUMP do not fulfil the criteria for malignancy but have at least 1 atypical

feature other than nuclear pleomorphism. This classification of GTUMP has evolved

from earlier criteria by Folpe et al (9)., with emphasis on nuclear

pleomorphism and other atypical features which include: infiltrative growth

pattern, high cellularity, necrosis, spindled morphology, large size (>2cm),

and deep location. However, cases lacking nuclear pleomorphism despite atypical

features pose challenges in exact categorization using WHO criteria. This case,

with focal moderate atypia but large size, deep location, and bronchial wall

infiltration, was categorized as GTUMP. Glomus tumours are consistently

positive for SMA; additional positive stains include vimentin, h-Caldesmon and

stromal collagen-IV. CD34 positivity has been reported in up to 32% of cases

(8). In these cases, a negative STAT6 can exclude a solitary fibrous

tumour.

Complete surgical excision with negative margins has

been recommended (9,10) for all cases. Chemotherapy has been employed in rare

cases of metastatic disease, following protocols similar to sarcomas (11).

Molecular studies of glomus tumours arising in various sites have shown the

occurrence of NOTCH gene fusions in more than half the cases (predominantly in

benign GT), less commonly, BRAF V600E and very rarely KRAS G12A mutations

(12,13). Most benign NOTCH-fusion positive GT occurred in extremities while the

malignant NOTCH positive tumours occurred in viscera (gastrointestinal tract

and lung). The identification of NOTCH gene rearrangement by FISH can help in

diagnosing a malignant glomus tumour in diagnostically challenging cases (12).

However, to the best of our knowledge, molecular markers that predict malignant

behaviour in GT have not been established so far; such a marker could aid in

cases of partially resected tumours and tumours with uncertain malignant

potential for deciding further treatment and follow-up. Next generation

sequencing of these tumours may facilitate identification of further molecular

alterations and thereby, potential targets for therapy.

Conclusion

Primary pulmonary Glomus tumors are rare lesions in

the bronchi or lungs, often mistaken for more common entities at these sites

and challenging to differentiate radiologically. Glomus tumours can exhibit

atypical or malignant features, necessitating comprehensive evaluation of all

specimens. Ambiguities persist in exact categorization of Glomus tumours with

uncertain malignant potential. While complete surgical excision remains the

preferred treatment, alternative options such as chemotherapy and targeted therapy

need to be explored. The identification of molecular markers to predict

malignancy and potential targets for treatment warrant further studies.

Etical approved

Written informed consent for publication was obtained

from the patient.

Author

contribution

Conceptualization: ShS, ShV, AK. Data curation:

ShS, ShV, AK, SK. Formal analysis: ShS, ShV, AK.

Investigation: SV, DV, AK. Methodology: ShV, AK. Administration:

ShV, AK. Resources: ShV. Software: ShV. Supervision: ShV,

AK. Validation: ShV, AK. Visualization: ShV, AK.

Writing—original draft: ShS, ShV. Writing— review & editing: ShV,

AK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors..

Conflict

of interest

There

is no Conflicts of interest/competing interests.

Funding

There

is no funding.

References

1. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 2008 Sep;132(9):1448-52.

2. Specht K, Antonescu CR. Glomus tumour. In:

WHO classification of tumours (5th edition) of soft tissue and bone.

Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). 2020:179–181.

3. Oide T, Yasufuku K, Shibuya K, Yoshino I, Nakatani

Y, Hiroshima K. Primary pulmonary glomus tumor of uncertain malignant

potential: A case report with literature review focusing on current concepts of

malignancy grade estimation. Respir Med Case Rep. 2016;19:143-9.

4. Jin Y, Al Sawalhi S, Zhao D et al. Behavior of

primary tracheal glomus tumor, uncertain malignant potential subtype. Gen

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 Nov;67(11):991-5.

5. Dai SH, Tseng HY, Wu PS. A glomus tumor of the lung

of uncertain malignant potential: A case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018

Dec;11(12):6039-41. Erratum in: Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019 Mar;12(3):1117.

6. Zhao SN, Jin Y, Xie HK, Wu CY, Li Y, Zhang LP.

Clinicopathological characterization of primary pulmonary and tracheal glomus

tumors. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020 Dec 8;49(12):1282-7.

7. Cunningham JD, Plodkowski AJ, Giri DD, Hwang S.

Case report of malignant pulmonary parenchymal glomus tumor: Imaging features

and review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 2016 Jan;40(1):144-7.

8. Mravic M, LaChaud G, Nguyen A, Scott MA, Dry SM,

James AW. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of glomus tumor: An

institutional experience of 138 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23(3):181-8.

9. Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, Weiss SW.

Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: Analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for

the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001 Jan;25(1):1-2.

10. Wood C, et al. Malignant glomus tumors: Clinical

features and outcomes. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2020;10:20.

11. Wolter NE, Adil E, Irace AL, et al. Malignant

glomus tumors of the head and neck in children and adults: Evaluation and

management. Laryngoscope. 2017 Dec;127(12):2873-82.

12. Agaram NP, Zhang L, Jungbluth AA, Dickson BC,

Antonescu CR. A molecular reappraisal of glomus tumors and related pericytic

neoplasms with emphasis on NOTCH-gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020

Nov;44(11):1556-62.

13. Chakrapani A, Warrick A, Nelson D, et al. BRAF and

KRAS mutations in sporadic glomus tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34: 533–535.