Introduction

Tenosynovial giant cell tumour (TGCT) is a rare mesenchymal¬ tumour that affects

joints and tendon sheaths. The diffuse-type TGCT has a high risk of relapse

following surgical resection of the tumour (1).

The classification of it can be categorised

into ‘nodular’ and ‘diffuse’ TGCT depending on the imaging findings of the

pathology. TGCT can be either benign or malignant – the likely incidence of

malignant TGCT is lower than that of benign TGCT at less than 1 per million per

year, with a mortality rate of around 30% and a metastatic rate of around 50%

(1). Estimates suggest that there are approximately 10 per million

persons/year for the localised type, while the diffuse type is about 4 per

million persons/year (2). Burton et al. highlights that little is known on the

burden of disease and that the common presentation of TGCT is benign (3). This

illustrates the rarity of the above condition.

A Japanese-authored article published by

Takeuchi et al., illustrated case reports of two cases of TGCT, with one having

an ocular cancer (Choroidal Melanoma), while the other was associated with

multiple type 1 neurofibromatosis (4). This is important as choroidal melanoma

is the second most common site of ten malignant melanoma sites in the body (5).

An article published in 2021 by Italian authors highlighted that pure muscle tenosynovial giant cell tumour mimics a metastasis in a

patient with melanoma. In this study, a 50-year-old female with a diagnosis of

malignant melanoma presented for a routine scan and an intense FDG focal uptake

corresponding to peri-trochanteric medial part of right iliopsoas muscle was

discovered (6). Once biopsied, the final diagnosis was derived. This is of

importance as the TGCT lesions may reproduce a malignant appearance on FDG-PET.

Hence, TGCT may be under-diagnosed as patient’s may be diagnosed as ‘metastatic

melanoma’ rather than biopsying the lesion which may

show that the histology is actually a second primary lesion. Furthermore, a

recent article published in 2025 by Patel et al. has documented that second

primary cancers does occur in the setting of melanoma. His focus looked at a

more common cancer (colo-rectal cancer) and

associations between the two. In this study, it was confirmed that it can be

influenced by various factors e.g. biological, lifestyle, genetic factors (7).

There were no other studies which are

published (to our knowledge) of a patient diagnosed with malignant melanoma who

also has malignant TGCTThere were no other studies

which are published (to our knowledge) of a patient diagnosed with malignant

melanoma who also has malignant TGCT.

Case presentation

Mr X, an 87-year-old South African male

with a background history of malignant melanoma (excised in 1982), in

remission; presented with shortness of breath and a cough. He was a non-smoker

and of sober habits and had a history of a pacemaker inserted for a

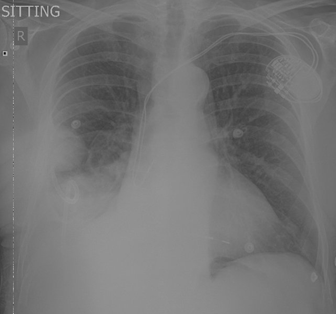

tachyarrhythmia. He had no other comorbidities. An initial baseline chest X-Ray

(CXR) performed on 26 May 2024 revealed a right pleural effusion (Figure 1).

This caused the shortness of breath in the patient and was considered treatable

as the fluid could be drained, which would lead to symptomatic relief.

Figure 1. CXR performed on 26 May 2024.

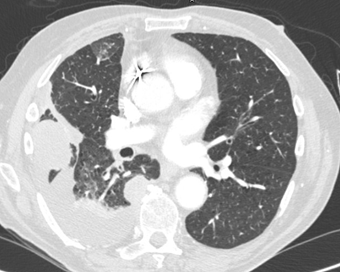

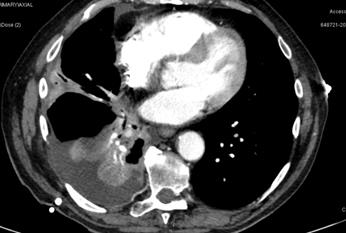

A CT scan was thereafter performed which

demonstrated multiple pleural-based nodules and masses,

the largest of which was adjacent to right 6th and 7th ribs and measured 3.3cm x 4.7cm (figure 2)

The second mass was noted adjacent to the right side

aspect of T8 and T9 vertebral bodies and measured 2.0 x 2.6cm (figure 3).

There was also associated pleural

thickening in the right costophrenic angle with an associated pleural based

lesion measuring 2.0 x1.9cm as well as a right hilar node which was 1.4cm (figure 4).

There was also a right large pleural

effusion.

Figure 2. CT scan: multiple pleural-based nodules and masses,

the largest of which was adjacent to the right 6th and 7th ribs.

Figure 3. The second mass was noted adjacent to the

right side aspect of T8 and T9 vertebral bodies.

Figure 4. Associated pleural thickening in the right

costo-phrenic angle with an associated pleural-based

lesion measuring 2.0 x 1.9 cm as well as

a right hilar node which was 1.4cm.

The patient was referred to the

cardio-thoracic surgeon and had a pleurocentesis

performed. After the drainage, the newer CXR demonstrated improvement in the

pleural effusion and unmasked a mass in the right lung which was previously

hidden by the fluid. There was right basal atelectasis and a small residual

right pleural effusion with a peripheral right mid-zone 51 mm nodule (See

Figure 5).

Figure 5. CXR post pleural tap.

Following this, Mr X had a pleural biopsy

via a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure and had a right

pleural drain inserted. The specimens were reviewed by a local histopathologist

at a private pathology laboratory and the patient was referred to the Oncology

unit for further work-up and management whilst awaiting histopathology results.

No PET scan was performed as the nearest

PET scanner is over 250km away from the Oncology Practice. With regard to

tumour markers (S100), the patient’s older records from his melanoma were not

available from the 1980s or 1990s. No S100 marker was done as the diagnosis was

not a metastatic lesion from the melanoma.

Immuno-histo-chemistry

Histology was done from the biopsy

specimens:

Initially, considering the clinical history

of previous malignant melanoma, a tentative diagnosis of metastatic malignant

melanoma with osteoclast-like giant cells was favoured (Table 1).

Table 1. Immuno-histochemical stains were done and revealed.

|

Marker |

Result |

Interpretation |

|

SOX-10 |

Negative |

Rules out melanocytic or neural crest

origin (e.g. melanoma, schwannoma). |

|

PRAME |

Positive in isolated cells |

PRAME is a non-specific marker; can be

seen in both benign and malignant settings. Not diagnostic. |

|

Calretinin |

Patchy Positive |

Suggests presence of mesothelial or

reactive mesothelial cells. Not specific to tumour. |

|

OSCAR |

Positive in scattered cells |

OSCAR (pan-cytokeratin) suggests focal

epithelial features, but not a dominant feature. |

|

BAP1 |

Positive (retained expression) |

Nuclear retention of BAP1 argues against

malignant mesothelioma. |

|

CD45 |

Positive in normal lymphocytes |

Confirms presence of background lymphoid

cells; tumour is not of lymphoid origin. |

|

HMB45 |

Negative |

Rules out melanoma and other PEComas. |

|

Vimentin |

Strongly and diffusely positive |

Suggests mesenchymal origin, which aligns

with many soft tissue tumours, including TGCT. |

|

MUM-1 |

Negative |

MUM-1 negativity excludes significant

plasma cell or lymphoid differentiation. |

|

WT-1 |

Patchy positive |

Highlights mesothelial or entrapped

mesothelial cells; not specific for the tumour itself. |

Key: SOX-10: transcription factor that is

part of a gene family with a DNA-binding HMG box domain; PRAME: preferentially

expressed antigen in melanoma; BAP1: OSCAR: Osteoclast-associated receptor;

BRCA1-associated protein; CD45: Cluster of Differentiation 45; HMB45: Human

Melanoma Black 45; MUM-1: multiple myeloma oncogene-1; WT-1: Wilms's Tumour

1; Due to the complexity of the case as

described in the Immuno-histochemistry stains seen (see Table 1), it was sent

to Cape Town for a second histopathological opinion, where a professor in

histopathology/cytopathology reviewed the diagnosis. This caused a delay in commencing treatment

of around 3 weeks for the patient.

Microscopy showed the following (verbatim):

“multiple cellular fragments of neoplastic tissue. Some of the fragments have

overlying surface fibrin. In some of the fragments collagenous areas are

present. The tumour comprised both solid and pseudo-alveolar areas. The solid

areas comprised diffuse groups of tumour cells. The tumour cells were

mononuclear with eosinophilic cytoplasm and slightly conspicuous nucleoli.

There were admixed macrophages. In addition, there were unevenly distributed osteoclast-type

giant cells. In other areas, the tumour cells were discohesive,

forming pseudo-alveolar structures. Within some of these areas, blood lakes

were present which were not lined by endothelium. Tumour cells were seen

floating in the blood lakes. In these blood lakes, hemosiderin-laden

macrophages were present. Some of the tumour cells are surrounded by fibrin. In

some of the more collagenous areas, these cells appear more spindled rather

than epithelioid. Mitotic activity is present. Melanin pigment was not appreciated”.

From Table 2, the

final diagnosis stated from the pleural biopsy was ‘Extra-Articular Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumour, Diffuse Type’.

Table 2. Repeat immunohistochemistry revealed the following findings.

|

Marker / Stain |

Result |

Interpretation |

|

OSCAR |

Positive

at periphery, negative in most cells |

Suggests

epithelial origin in periphery; not significant overall |

|

CD45 |

Scattered

positive cells |

Scattered

lymphoid cells; not a lymphoid neoplasm |

|

Calretinin |

Scattered

cytoplasmic positivity in mesothelial cells |

Highlights

entrapped/reactive mesothelial cells |

|

BAP-1 |

Diffuse

nuclear retention |

No loss;

argues against mesothelioma |

|

WT-1 |

Weak

nuclear positivity in many cells |

Highlights

mesothelial cells; not tumour-specific |

|

Vimentin |

Diffuse

positive staining |

Consistent

with mesenchymal origin |

|

HMB45 |

Negative |

Rules out

melanoma |

|

SOX-10 |

Negative |

Rules out

neural crest tumours (e.g., melanoma, schwannoma) |

|

PRAME |

Some

nuclear positivity |

Non-specific;

seen in some neoplastic and benign processes |

|

MUM-1 |

Scattered

positivity in plasma cells |

Reflects

background immune cells |

|

Melan A |

Negative |

Rules out

melanoma |

|

CD68 |

Diffuse

positive; highlights multinucleated giant cells |

Typical

for histiocytic origin in tenosynovial giant cell

tumour |

|

p63 |

Interpreted

as negative |

Argues

against epithelial or myoepithelial differentiation |

|

AE1/AE3 |

Positive

in some cells, similar to OSCAR |

Focal

epithelial marker expression; non-specific |

|

ERG |

Positive

in blood vessels only |

Normal

vascular staining; not tumour-specific |

|

Desmin |

Scattered

positive tumour cells |

Suggests

some myoid differentiation; may be non-specific |

|

Perl’s

Prussian Blue |

Positive

in hemosiderophages and some tumour cells |

Indicates

iron deposition; common in tenosynovial giant cell

tumour |

Key: SOX-10: transcription factor that is

part of a gene family with a DNA-binding HMG box domain; PRAME: preferentially

expressed antigen in melanoma; BAP1: OSCAR: Osteoclast-associated receptor;

BRCA1-associated protein; CD45: Cluster of Differentiation 45; HMB45: Human

Melanoma Black 45; MUM-1: multiple myeloma oncogene-1; WT-1: Wilms's Tumour

1; PRAME: PReferentially

expressed Antigen in Melanoma; CD68: Cluster of Differentiation 68; AE1/AE3:

Anion Exchanger 1/ Anion Exchanger 3; ERG: ETS-related gene.

Oncology

Mr X presented to

Oncology on 5 June 2024, with a history of shortness of breath and cough. A

working diagnosis of recurrent metastatic malignant melanoma was favoured at

the time, based on histopathological morphological findings and the previous

clinical history of melanoma. He had an ECOG performance status of 2 and was

planned for systemic therapy for metastatic malignant melanoma.

After review of

the updated histopathology report and the diagnosis of TGCT, Imatinib was

considered as part of the therapeutic options as well as radiotherapy to the

large thoracic masses for symptomatic control.

Other treatment options were not available and Denosumab would have been

a good choice, but Mr X had more visceral disease than skeletal involvement.

From the initial presentation, his condition declined.

On 18 July 2024, a repeat CT scan was

performed. It showed significant disease progression in the necrotic pleural

based mass along the right hemithorax with right lower zone empyema. There was

also mediastinum and right hilum lymphadenopathy present.

Mr X also had a CT scan of the brain as he

was confused to exclude brain metastases which came back negative.

The patient

ultimately succumbed to his illness and passed away on 22 July 2024.

Discussion

A South African

article published by Tontu et al. in 2024, described

Denosumab in managing TGCT in a 21-year-old female (8). Unfortunately, in our

patient, this drug was not available. Furthermore, in Mr X, it was initially

thought that the lung lesion was a metastatic lesion, rather than second

primary lesion. It has been found that a biopsy of a suspicious lesion can

confirm if there is a relapse of the tumour or exclude the second primary

tumour in metastatic lesions (9). We postulate that biopsies of suspected

(likely) metastatic lesions may reveal that some of these lesions may actually

be a second primary lesion. This could impact management as a different regimen

of drugs may be considered. An article published by Zheng et al. supports this

as it was found that around 25% of patients diagnosed with cancer have a second

primary malignancy (10). Another interesting finding from Mr X was the

association with melanoma. This case may support a rare co-occurrence, although

causality is unproven between TGCT and melanoma, as this would be the second

case documented (to our knowledge) of such an association in such a rare

condition.

Immunohistochemistry

assisted greatly with the diagnosis. The initial comment from the

histopathologists mentioned that “Vimentin positivity may be seen in melanoma,

however, the negative SOX-10, HMB45 and only patchy positive PRAME, demand that

other possibilities be considered. Vimentin positivity is seen in a host of

other tumours including mesothelioma (excluded with calretinin and BAP1

stains), sarcomas and giant cell tumours, the latter of which may be considered

in this case given the morphology of the tumour, except the tumour site is

quite unusual” (11). Considering this and the second opinion of an expert

immuno-histopathologist, the diagnosis was male.

The “best

clinical management of tenosynovial giant cell tumour

(TGCT): A consensus paper from the community of experts” published in 2022 was

designed to assist with helping clinicians with the management of TGCT (1).

Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors are effective for

symptomatic benefit and improves the quality of life of patients with TGCT but

is not available in many countries (1). In South Africa, this drug is not

available; however, a drug with the tradename “Turalio”

is available for treatment of TGCT internationally (12). If a patient is diagnosed with TGCT, it is

recommended that they go to expert centres with experienced sarcoma

multidisciplinary treatment team (1). Thereafter a joint decision can be made

about active surveillance vs active treatment, surgery, radiotherapy,

cryotherapy or systemic treatment (1). In South Africa, teams like this exist

in Cape Town; however, given the patient’s advanced stage of disease, he was

not considered for referral for this multidisciplinary team. It is likely that

the delay in commencing treatment also led to the progression of disease in

this patient, highlighting the need for referring patients like this to such teams.

With regards to

clinical decision making, Imatinib was used as it inhibits the tyrosine kinase

activity of the CSF1R, which is an important protein which affects the growth

and proliferation of these tumours. Using this drug would result in the pathway

being blocked, which would lead to shrinkage of the tumour which would improve

symptoms (13). The other drug considered

was Denosumab which is a systemic monoclonal antibody against the Receptor

Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B (RANK) ligand, which has been used in

patients with giant cell tumours of the bone (14). Our rationale of using

Imatinib over Denosumab was that Denosumab is used for bone metastasis in most

cases. In the case of Mr X, there was no clear evidence of bone involvement so

Imatinib was favoured as his tumour showed mostly soft tissue (lung parenchyma)

involvement. Of note, there isn’t a clear guideline or consensus on this as the

case is uncommon.

Conclusion

TGCT is a rare condition which may or may

not be associated with melanoma. We recommend that suspected metastatic

melanoma lesions be biopsied to establish or refute this association.

Acknowledgement

Pathcare (private

laboratory) assisted with the Histopathology on this case. We would like to

thank the histopathologists who were involved in producing the pathology reports:

Dr Jaravaza, Dr Sengoatsi

and Prof Govender.

Author contribution

RRC and SK were both involved in writing/editing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest associated with this

paper.

Funding

There is no funding.

Ethical considerations

All information was anonymised to ensure

patient confidentiality. Permission for using anonymised patient data was

granted by Cancercare.

References

1. Stacchiotti

S, Durr HR, Schaefer IM et al. Best clinical management of tenosynovial

giant cell tumour (TGCT): A consensus paper from the

community of experts. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023 Jan; 112:102491.

2. Aboo

FB, Kgagudi PM. Tenosynovial

giant cell tumour: current concepts review and recent

developments focusing on pathogenesis and treatment-directed classification. SA

Orthop J. 2025;24(2):90-93.

3. Burton TM, Ye X, Parker

ED, Bancroft T, Healey J. Burden of Illness Associated with Tenosynovial

Giant Cell Tumours. Clin Ther. 2018 Apr;40(4):593-602.

4. Takeuchi A, Yamamoto N,

Hayashi K et al. Tenosynovial giant cell tumours in unusual locations detected by positron emission

tomography imaging confused with malignant tumours:

report of two cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016 Apr 26(17):180.

5. Singh P, Singh A.

Choroidal melanoma. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2012

Jan;5(1):3-9.

6. Arcuri PP, Commisso A,

John M, Cascini GL, Laganà D. Pure muscle tenosynovial giant cell tumour mimicks a metastasis in patient with melanoma. J Clin

Images Med Case Rep. 2021; 2(4):1242.

7. Patil S, Jeyakumar A,

Gopalan V. Melanoma and Colorectal Cancer as Second Primary Cancers: A Scoping

Review of Their Association and the Underlying Biological, Lifestyle, and

Genetic Factors. J Gastrointest Canc. 2025.(56):125.

8. Tontu

NA, Miseer S, Burger H. Denosumab in irresectable

giant cell tumour of the cervical spine. South

African Journal of Oncology. 2024; 8(0), a303.

9. Qu Q, Zong Y, Fei XC et

al. The importance of biopsy in clinically diagnosed metastatic lesions in

patients with breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2014 Apr (10):934.

10. Zheng X, Li X, Wang M et

al. Multidisciplinary Oncology Research Collaborative Group (MORCG). Second

primary malignancies among cancer patients. Ann Transl

Med. 2020 May; 8(10):638.

11. Pathcare Laboratories.

Confidential Histopathology Patient Report. 17 July 2024.

12. Dharmani

C, Fofah O, Fallon M, Rajper

AW, Wooddell M, Salas M. TURALIO® Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy

Program (tREMS): 3-year retrospective hepatic safety

assessment. Future Oncol. 2024;20(33):2559-2564.

13. Cassier PA, Gelderblom H, Stacchiotti S et

al. Efficacy of imatinib mesylate for the treatment of locally advanced and/or

metastatic tenosynovial giant cell tumor/pigmented

villonodular synovitis. Cancer 2012;118:1649-1655.

14. Tontu

NA, Miseer S, Burger H. Denosumab in irresectable

giant cell tumour of the cervical spine. S. Afr. J.

Oncol. 2024; 8(0), a303.