Figure 1. Schematic of selected potential tumor antigens of renal cell carcinoma.

Exploring neoantigens and genetic profiles in renal

cell carcinoma: a study of Iranian patients

Zohreh Mehmandoostli

1,2, Mahmood Dehghani Ashkezari 1,2,

Seyed Morteza Seifati 1,2, Amirreza Farzin 3, Gholam Ali Kardar 4,5*

1 Department of Biology, Ashk.C., Islamic

Azad University, Ashkezar, Iran

2 Medical Biotechnology Research Center, Ashk.C.,

Islamic Azad University, Ashkezar, Iran

3 Uro-Oncology Research Center, Tehran University of Medical

Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4 Immunology, Asthma and Allergy Research Institute (IAARI), Tehran University

of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5 Department of Medical Biotechnology, School of Advanced

Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

* Corresponding Author:

Gholam Ali Kardar

* Email: gakardar@tums.ac.ir

Abstract

Introduction: Kidney cancer

accounts for 3.7% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases and represents a

considerable global health challenge. Although there have been advancements in

treatment, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) continues to show resistance to

conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, highlighting the need for innovative

therapeutic strategies. Current research is focusing on vaccine approaches that

target tumor neoantigens, utilizing next-generation sequencing to pinpoint

tumor-specific mutations. A deeper understanding of the molecular

characteristics of RCC, particularly gene mutations such as BAP1, PBRM1, SETD2,

and VHL, is essential for the development of personalized treatment modalities.

This study aimed to investigate potential tumor neoantigens in samples from Iranian

patients diagnosed with RCC, with an emphasis on peptide sequences that exhibit

a strong binding affinity for Iranian Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA).

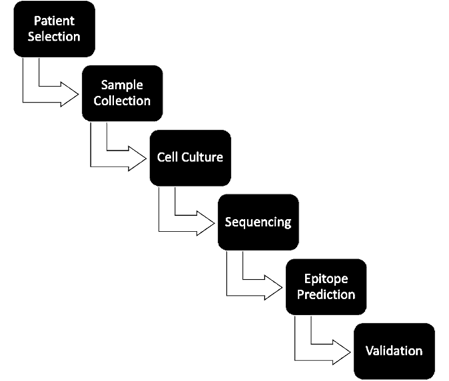

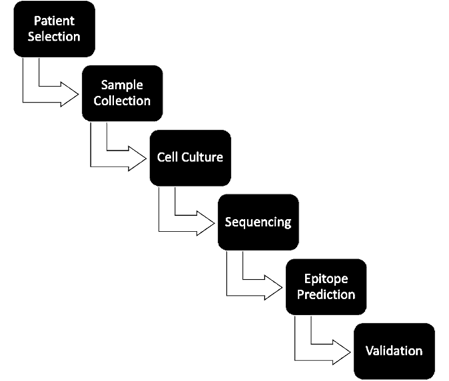

Materials and

methods: Databases and

relevant literature were employed to identify neoantigens with the highest

prevalence. Tumor samples were obtained from patients with RCC, and primary

cells were isolated and cultured in RPMI complete medium. Total DNA was

extracted, followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specifically

designed primers, and the resulting PCR products were sequenced using Sanger

sequencing.

Results: Our examination did not identify the specified nucleotide changes in

the DNA sequencing chromatogram of the cell samples, indicating that the

anticipated mutations were absent. Nevertheless, other mutations were observed

in the analyzed regions of the genes.

Conclusion: Although certain mutations were not identified in the sequenced

samples, this research highlights the necessity for further investigation.

Comprehensive studies are vital to gain a complete understanding of the genetic

mutation profile of RCC in Iranian patients. Mapping the gene mutation

landscape among RCC patients in Iran presents significant opportunities for the

development of effective cancer vaccines and tailored treatment strategies.

Keywords: Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA), Renal cell carcinoma, Tumor, Mutation,

Vaccines

Introduction

Kidney cancer represents 3.7% of newly diagnosed cancer cases and

ranks among the ten most prevalent cancers. The predominant type, RCC, is found

in 85% of kidney cancer instances. This condition is more prevalent in men than

in women, with a ratio of 1.7:1, and it generally affects older adults, with an

average age of 64 at diagnosis (1). The rate of metastasis is notably high, as 30% of patients are

diagnosed with metastatic disease, and an additional 30% develop metastases

during subsequent follow-ups (2). Renal cell carcinomas can be categorized into clear cell (CCRCC),

papillary (PRCC), and chromophobe (ChRCC) subtypes,

which account for 65-70%, 15-20%, and 5-7% of all RCC cases, respectively (3). Recent research has identified genetic factors, including

mutations in the VHL, PBRM1, BAP1, and SETD2 genes, as significant contributors

to the risk of developing RCC (4).

Among the

innovative strategies for treating RCC, antigen-directed approaches such as

monoclonal antibodies, adoptive cell therapies, and therapeutic vaccines show

promise in enhancing the effectiveness of existing immunotherapies (5). Various neoantigen vaccine platforms, including synthetic long

peptide (SLP), RNA, dendritic cell (DC), and DNA vaccines, are currently

undergoing evaluation in early-phase clinical trials (6). The SLP vaccine platform has emerged as the most extensively

studied neoantigen vaccine in preclinical and early-phase clinical settings,

offering notable advantages such as a well-established safety profile, a

thoroughly characterized GMP manufacturing process, excellent stability, and

ease of administration in human trials (7). The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has

further expedited the discovery of tumor-specific mutations, facilitating the

development of more targeted and personalized treatment strategies (8).

Recent studies

have validated the therapeutic promise of SLP neoantigen vaccines across

various human cancers, including melanoma, glioblastoma, non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer, and urothelial cancer (9-13). A clinical trial involving the peptide-based neoantigen vaccine

iNeo-Vac-P01 in patients with advanced solid tumors revealed a favorable safety

profile and encouraging efficacy, achieving a 71.4% disease control rate and

robust immune responses in nearly 80% of participants (9). In this context, Ott et al. have undertaken multiple

investigations. In one study involving six melanoma patients, clinicians

administered up to 20 neoantigens per individual. Remarkably, four patients

with stage IIIB/C disease experienced no recurrence over a 25-month period,

while two patients with previously untreated stage IVM1b disease (lung

metastases) achieved complete regression following vaccination and subsequent

anti-PD-1 therapy (12). Similar findings were reported in glioblastoma patients (11). Furthermore, Ott et al. introduced a neoantigen-based vaccine,

NEO-PV-01, in conjunction with PD-1 blockade for patients with melanoma, NSCLC,

or bladder cancer. This vaccine elicited CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses

post-vaccination, characterized by a cytotoxic phenotype capable of

infiltrating tumors and inducing tumor cell destruction. The treatment was

deemed safe, with no adverse events reported (NCT02897765) (13).

In tumor cells,

mutations can lead to the formation of novel self-antigen epitopes, referred to

as neoantigens. The advent of NGS has created opportunities for the efficient

and cost-effective identification of tumor-specific mutations in individual

patients, facilitating the exploration of therapies targeting these mutated

proteins in clinical trials studies (14). This process encompasses several stages, including the collection

of tumor samples, sequencing, bioinformatic analysis, and peptide synthesis,

all of which demand considerable time and resources. Despite advancements in

sequencing technology facilitating rapid progress, the identification and

validation of neoantigens remain labor-intensive and costly, with the

preparation of vaccines from tissue samples typically requiring 3 to 5 months (15, 16).

In RCC, the

scenario is different because RCC is a cancer with low mutational burden (17).

Neoantigens can be divided into two categories: shared neoantigens (public

neoantigens) and personalized neoantigens. Off-the-shelf vaccines are designed

to target shared neoantigens, which are anticipated to have a high expression

frequency and provoke strong anti-tumor immune responses, thus making them

suitable for a wider array of cancer specially RCC patients (18). The molecular profiles of RCC have been examined through NGS in

various research initiatives, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and

other studies conducted in France, Japan, and the European Union (19). Wang et al. analysis of

individual gene mutations was shown that the most prevalent mutations include

PBRM1 (74.1%), BAP1 (74.1%), SETD2 (74.1%), and VHL (74.91%) (20). In our forthcoming research aimed at developing an off-the-shelf

peptide vaccine, we explored potential tumor neoantigens in RCC samples

collected from Iranian patients, focusing on peptide sequences with a strong

affinity for the Iranian HLA.

Materials and methods

3.1. Data

sources

A genomic analysis of RCC data was performed using the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Literature reviews and original articles were also investigated to

find RCC mutations. The potential neoantigens were explored using cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org, v3.2.11). The Human Gene Mutation

Database (HGMD, www.hgmd.com) was used to select peptide sequences considering a moderate to strong

affinity for Iranian HLA binding. The bioinformatics analysis included the

prediction of MHC I-binding epitopes using tools such as NetMHCpan

(v4.0) to identify peptides with a moderate to high affinity for HLA molecules.

3.2. Patients

and samples

Cancerous tissues were obtained from patients diagnosed with RCC

following surgical procedures at the Department of Urology at Imam Khomeini

Hospital. Pathologists verified the pathological features of these samples

through histopathological analysis. The section on Ethical Considerations

outlines the ethical approval for utilizing the primary cells of patients, with

written informed consent secured from all participants (Ethical Approval Code:

IR.TUMS.IAARI.REC.1399.010). The inclusion criteria specified that participants

must be diagnosed with RCC and have not received any prior treatment. Patients

with different histological subtypes of RCC or those who had previously

undergone treatment were excluded from the study.

3.3. Primary Cell

Culture

RCC solid tumor tissue was first rinsed

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then cut into pieces measuring

approximately 1-2 mm. The tissue was subsequently filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer without the use of enzymatic

digestion. The resulting filtered cells were washed twice with PBS and cultured

in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1X

Penicillin-Streptomycin (Pen/Strep) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 and 95%

humidity for a duration of 72 hours. Following this incubation, the suspended

cells were removed by washing with sterile PBS. The adherent cells were then

maintained in fresh RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 1X Pen/Strep for one

week, allowing them to achieve 90% confluency. The cells were subsequently passaged

using Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) and seeded at a density of 1x106 cells

per T-75 flask for further experimentation.

3.4. DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction

To validate the potential neoantigen peptides in cultured cells,

adherent cells were harvested. Total DNA was extracted utilizing the SanPrep Column DNA Miniprep Kit (Bio Basic,

Canada) in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. The PCR was performed

using Taq DNA Polymerase 2x Master Mix and 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Ampliqon,

Denmark), following the standard protocol with an annealing temperature of 58°C

for the primers. Specific primers for the peptides were designed using Primer3.

To ensure the specificity and accuracy of the designed primers, their sequences

were subjected to a BLAST search in NCBI and Gene Runner. The sequences of the

primers are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. The details of oligonucleotide primers

utilized for PCR.

|

Reverse Primer |

Forward Primer |

Gene |

|

|

525 bp |

GCTTCAGACCGTGCTATCGT |

GCGTTCCATCCTCTACCGAG |

VHL (1) |

|

334 bp |

ACGTACAAATACATCACTTCCATTT |

ACCGGTGTGGCTCTTTAACA |

VHL (2) |

|

579 bp |

CGATATGCTGCAATTCCCACT |

GGCAAAGCCTCTTGTTCGTT |

VHL (3) |

|

217 bp |

CCATGCTGGAGTACAGTGAGTT |

TGATGCACATATCCTGGAGAAGTTA |

PBRM1 |

|

555 bp |

AGCAGTTGAGCCAGGGAATC |

GCTGCTCTCTGAAGCTTTGC |

BAP1 |

|

310 bp |

TTAATGGTCAGAACAGCAATCGTG |

AAACTTTGAAGCTGGTAGTCAGGA |

SETD2 |

|

167 bp |

GAGGCTGGGGCACAGCAGGCCAGTG |

CTCCTAGGTTGGCTCTG |

TP53 |

|

451 bp |

CCCCTGAGAAGCAGTCTGTG |

GCTGGGGAGGTTTCATGGAG |

FLCN |

|

250bp |

CTGAGATCAGCCAAATTCAGTT |

GGGAAAAATATGACAAAGAAAGC |

PIK3CA (1) |

|

241bp |

TGGAATCCAGAGTGAGCTTTC |

CTCAATGATGCTTGGCTCTG |

PIK3CA (2) |

3.5. Analysis

of PCR Product

The PCR products underwent sequencing at Pishgam

Co. in Iran, utilizing the Sanger sequencing technique. Following the

amplification of the selected mutant regions with the specified primer sets

(refer to Table 1), a total of 10 PCR product samples were dispatched for

sequencing. The sequencing chromatograms were first analyzed using Chromas Lite

v.2.5 software, followed by alignement and comparison

to reference sequences using CLC Sequence Viewer 7.7.1 software to investigate

the potential presence of neoantigen mutations in the cultured primary tumor

cells.

Ethical

consideration

The Vice Chancellor for Research Affairs at Tehran University of

Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, granted approval for the acquisition of the

primary cell culture utilized in this study (Ethical Approval Code:

IR.TUMS.IAARI.REC.1399.010). All procedures conducted adhered to the ethical

standards set forth by both the institutional and national research committees,

as well as the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or

equivalent ethical guidelines.

Data Analysis

Statistical methods were not applied in the analysis of sequencing

data. Instead, descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize the frequency

and distribution of the identified neoantigens. Additionally, bioinformatic

tools, including NetMHCpan 4.1, were employed to

predict the binding affinity of the identified peptides to HLA molecules.

Results

4.1.

Bioinformatic Data

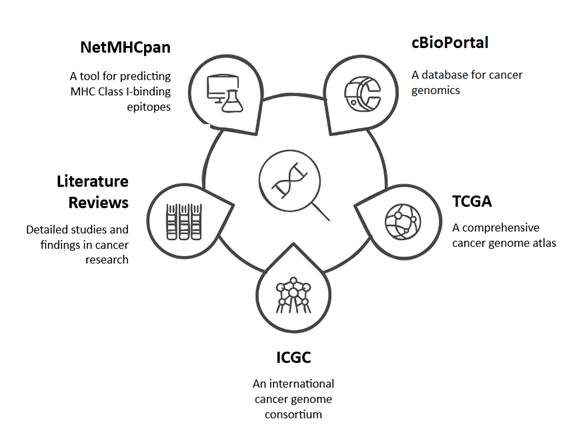

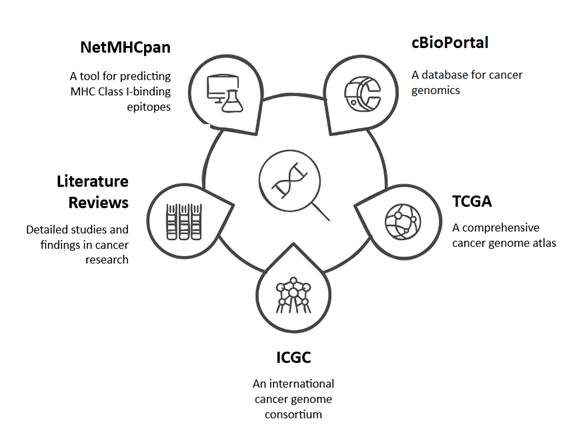

The potential tumor antigens associated with RCC were identified

through the utilization of cBioPortal, The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA), the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) cohorts,

and comprehensive literature reviews. Following the identification of the most

prevalent antigens exhibiting mutations, involve of 17 mutations from 7 genes

(VHL, PBRM1, BAP1, SETD2, TP53, FLCN, and PIK3CA). By advantage of

bioinformatics tools, including NetMHCpan (v4.1),

MHC-I binding epitopes predication, common Iranian population MHC-I are

HLA-B*35:01, HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*24:02, HLA-B*51:01, HLA-A*03:01, and

HLA-A*01:01, in both wild-type and mutant of 1105 nine-mer

peptides were done. Mutant peptides with moderate to high binding affinities in

compare to wild type were selected based on their predicted binding

capabilities. Finally, based on Table 2, twenty nine peptides were selected (15,21).

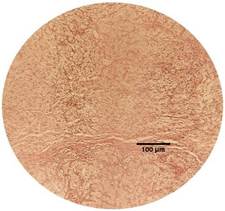

A summary of the RCC potential tumor antigens data, along with the

common MHC-I alleles in the Iranian population, is presented in Figure 1 and

Table 2.

Figure 1. Schematic of selected potential tumor antigens of renal cell carcinoma.

Table 2. The details of selected potential tumor

antigens of Renal Cell Carcinoma. The peptides with strong binding affinity

to HLA were shown with green color. peptides exhibiting moderate to strong

HLA-binding affinity (IC50 < 150 nmol/l) being more likely to activate CD8+

T cells.

|

Gene |

Mutation |

Immunizing peptide |

HLA |

Binding Affinity (nM) |

|

|

Wild |

Mutant |

||||

|

VHL |

W88L |

SPRVVLPVL |

HLA-B*35:01 |

3839.92 |

1613.19 |

|

VVLPVLLNF |

HLA-A*24:02 |

376.32 |

1420.44 |

||

|

H115Y |

SYRGYLWLF |

HLA-A*24:02 |

14.56 |

12.14 |

|

|

D121Y |

RYAGTHDGL |

HLA-A*24:02 |

26237.97 |

387.69 |

|

|

V130F |

GLLFNQTEL |

HLA-A*02:01 |

176.25 |

108.44 |

|

|

LLFNQTELF |

HLA-A*24:02 |

4051.01 |

2081.94 |

||

|

LLFNQTELF |

HLA-B*35:01 |

1934.56 |

1456.79 |

||

|

N131K |

GLLVKQTEL |

HLA-A*02:01 |

176.25 |

197.59 |

|

|

GTHDGLLVK |

HLA-A*03:01 |

22426.29 |

342.46 |

||

|

LLVKQTELF |

HLA-A*24:02 |

4051.01 |

2578.81 |

||

|

LLVKQTELF |

HLA-B*35:01 |

1934.56 |

2834.24 |

||

|

L135F |

LVNQTEFFV |

HLA-A*02:01 |

736.1 |

140.49 |

|

|

LLVNQTEFF |

HLA-B*35:01 |

1934.56 |

1702.89 |

||

|

I151T |

FANTTLPVY |

HLA-A*01:01 |

2066.66 |

1207.22 |

|

|

TTLPVYTLK |

HLA-A*03:01 |

31.53 |

39.98 |

||

|

FANTTLPVY |

HLA-B*35:01 |

4.85 |

3.96 |

||

|

L169P |

LQVVRSPVK |

HLA-A*03:01 |

807.91 |

1784.2 |

|

|

PBRM1 |

G626V |

VPLPDDDDM |

HLA-B*35:01 |

416.12 |

58.65 |

|

BAP1 |

F170V |

RTMEAFHVV |

HLA-A*02:01 |

7.22 |

29.91 |

|

RTMEAFHVV |

HLA-A*24:02 |

588.39 |

703.75 |

||

|

MEAFHVVSY |

HLA-B*35:01 |

59.51 |

62.01 |

||

|

EAFHVVSYV |

HLA-B*51:01 |

2045.28 |

1749.79 |

||

|

SETD2 |

H1629Y |

NMYSCEPNC |

HLA-A*02:01 |

12006.73 |

3790.55 |

|

TP53 |

R248L |

NLRPILTII |

HLA-A*02:01 |

26600.99 |

3128.28 |

|

MNLRPILTI |

HLA-A*24:02 |

9934.93 |

3516.92 |

||

|

FLCN |

R18H |

ELHGPHTLF |

HLA-A*24:02 |

16730.88 |

8074.98 |

|

ELHGPHTLF |

HLA-B*35:01 |

13223.15 |

9173.56 |

||

|

PIK3CA |

E542K |

ISTRDPLSK |

HLA-A*03:01 |

35089.89 |

930.82 |

|

H1047L |

ALHGGWTTK |

HLA-A*03:01 |

5388.83 |

47.14 |

|

4.2.

Pathological Characteristics of RCC

The identification of renal cell tumor was validated through

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig.1). This staining technique

allowed for a comprehensive visualization of cellular morphology and tissue

structure, thereby affirming the presence of distinctive characteristics

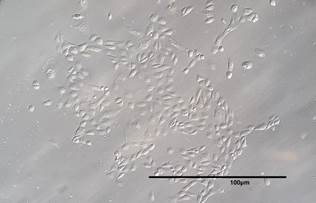

associated with RCC. Following a one-week culture period, RCC cells were

analyzed using an inverted microscope to assess their morphology and growth

patterns (Fig.2). The cells displayed the typical morphological traits of RCC,

characterized by clear cytoplasm and well-defined cell boundaries. Finally, 10

RCC patient cells were selected for DNA sequencing.

Figure 2. Two different RCC tissues from the studied patient #008 were stained

with the hematoxylin-eosin staining method.

Figure 3. Primary RCC cell obtained from patient #004 (20X magnification).

Table 3. The patient demographics of those with RCC who used their tumor samples

for the study.

|

Patient No. |

Sex |

Age (Years) |

Diagnosis |

|

01 |

Female |

46 |

Clear cell |

|

02 |

Male |

53 |

Chromophobe |

|

03 |

Male |

41 |

Clear cell |

|

04 |

Female |

48 |

Clear cell |

|

05 |

Male |

39 |

Papillary |

|

06 |

Female |

46 |

Clear cell |

|

07 |

Male |

71 |

Clear cell |

|

08 |

Male |

45 |

Clear cell |

|

09 |

Male |

66 |

Papillary |

|

10 |

Female |

74 |

Chromophobe |

4.3 Sanger

Sequencing Analysis

The results from Sanger sequencing revealed that the expected mutations

were absent in the analyzed samples when compared to the reference sequences.

However, additional mutations in the analyzed genes, which are not the chosen

mutations, were observed. Below are some of those mutations found in the

sequenced regions that include: PIK3CA p.Leu1067del,

VHL L135I, VHL c.491delA (p.Gln164ff), TP53 D259E, …

This discrepancy indicates that the identified neoantigens may not be

common among Iranian RCC patients. To validate these findings, additional

sequencing with a larger sample size may be required.

Discussion

The global

incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is on the rise, with an estimated

mortality rate of approximately 20% (22). Neoantigen-based vaccines may prove effective for patients

suffering from metastatic RCC, potentially leading to improved overall survival

rates, diminished tumor burden, and a reduction in cancer progression (23). It is crucial to identify tumor-associated antigens that are

specific to RCC and to develop strategies to counteract tumor-induced

immunosuppression, thereby making vaccine therapy a feasible treatment option (24). The ideal antigen should be exclusive to tumor cells, vital for

tumor initiation and progression, identifiable by the immune system, and

capable of inducing cytotoxic effects on tumor cells (25). Although numerous tumor antigens show promise, only a limited

number meet the criteria for tumor selectivity and robust immune response

activation, underscoring the necessity for ongoing research and development in

this field (26). Previous investigations have confirmed the safety and feasibility

of employing mutated VHL peptides as a vaccine for metastatic RCC (27). In the majority of ccRCC cases,

mutations in genes such as SETD2, BAP1, MTOR, PTEN, KDM5C, and PBRM1 are

frequently observed in the chromosome 3p regions, alongside VHL gene mutations (28). Recent research has emphasized the potential of these mutations

as targets for innovative therapeutic strategies, indicating that a

multi-targeted vaccine approach may enhance the efficacy of RCC immunotherapy.

In a study conducted by Razafinjatovo et al. in 2017,

DNA samples from 30 ccRCC patients were analyzed

through NGS, focusing on a specific panel of 18 genes, including VHL, BAP1,

HIF1a, PDGFRA, PDGF(R)B, TP53, CARD11, NFkB, TSC1,

MTOR, EGFR, PBRM1, SETD2, KDM5C, KDM6A, PTEN, and PIK3CA, all of which are

known to harbor mutations in ccRCC. Frequent

mutations in these genes were detected, and their mutational status,

particularly in genes such as PBRM1, BAP1, CARD11, and HIF1α, was

correlated with responses to targeted therapies, potentially serving as

predictors of therapeutic outcomes in ccRCC patients (29).

These findings

have established a basis for the identification of potential tumor antigens.

The advent of advanced sequencing technologies has facilitated more accurate

and thorough analyses of these mutations, thereby deepening our comprehension

of their significance in RCC. Such insights are vital for the creation of

targeted vaccines and personalized therapies that can effectively address the

genetic diversity present in RCC tumors. Recent investigations have indicated

that neoantigen-based vaccines administered to RCC patients have shown

encouraging outcomes. Nevertheless, two major challenges persist in this area.

The first challenge is the impracticality of a peptide-based approach due to

prohibitive costs and time demands (30). For example, while a particular study reported positive outcomes,

the process was impeded by these financial and temporal constraints (12). The application of NGS techniques for personalized treatment and

the identification of neoantigens may prove to be highly effective. Research

conducted by Bles and Ott (2021) has illustrated that personalized

neoantigen-based vaccines, supported by rapid sequencing technologies and

bioinformatics, exhibit strong immunogenic profiles and preliminary indications

of anti-tumor efficacy in melanoma patients. Furthermore, findings from Ott et

al. (2017) highlight that these vaccines can provoke robust anti-tumor immune

responses and contribute to tumor size reduction in certain melanoma patients (31, 32).

In this

context, the exploration of universal peptides as an alternative strategy is

particularly compelling. Universal peptides are present across a wide range of

cancer types and have the unique ability to stimulate immune responses against

multiple tumors simultaneously. This capacity enables them to activate various

subsets of T cells, positioning universal peptides as promising candidates for

broad-spectrum vaccines in cancer therapy. The NeoVax

brand is focused on identifying and utilizing these universal peptides to cater

to different cancer types. By adopting this approach, we can significantly

reduce the time and costs associated with the collection of individual tumor

samples while ensuring a consistent method of application. This could provide a

hopeful pathway for addressing the challenges faced in the treatment of RCC and

other cancers.

However, there

remains a substantial gap in research specifically addressing the application

of these vaccines for renal cell carcinoma. This shortfall may be attributed to

the distinct genetic characteristics of RCC, which exhibit unique mutational

patterns different from those seen in melanoma. Moreover, the tumor

microenvironment in RCC can significantly impact the immune system’s ability to

recognize and respond to neoantigens.

In our

research, we carefully examined a variety of potential tumor antigens from

samples collected from Iranian patients, as outlined in Table 2. While we

started with optimistic expectations, we found that we could not validate the

mutations in the sequenced samples from Iran. This lack of confirmation might

be influenced by several factors, including sample heterogeneity and varying

mutation frequencies among patients in this population. Future investigations

should prioritize the use of higher coverage sequencing methods and an expanded

sample size to address these challenges. Furthermore, incorporating additional

techniques like whole exome sequencing (WES) or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) could

yield a more thorough understanding of the genetic landscape of RCC across

diverse populations(33, 34). The genetic profile of renal tumors exhibits spatial variation

within individual tumors as well as differences among patients. There is a

notable deficiency in data concerning the intratumor heterogeneity present

across various racial groups. Preliminary evidence indicates that genetic

variations may exist among different racial demographics affected by RCC,

warranting further investigation (35). For instance, analysis of the TCGA database reveals that black

patients demonstrate elevated expression of BAP1 at the genetic level (36). Future studies should focus on clarifying the degree of genetic

heterogeneity within RCC tumors and its potential implications for personalized

treatment strategies. Gaining insight into these variations is crucial for the

development of targeted therapies that are more effective for distinct racial

and ethnic populations.

Conclusion

Author

contribution

ZM, GAK, formal analysis, investigation, data curation,

visualization, and writing original draft preparation. GAK,

conceptualization, methodology, validation, and project administration. GAK,

writing review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition. AF made

significant contributions to the preparation of the primary cells. MDA

contributed to the study and problem-solving related to the paper, writing

review and editing. SMS contributed to writing, reviewing and editing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

The author

declares no conflict of interest.

Funding

The ethical

committee of Tehran University of Medical Science confirmed this study [Ethic

no. IR.TUMS.IAARI.REC.1399.010].

Consent for

publication

All authors

have reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication. All

participants provided informed consent for their data and images to be

published.

Funding

Tehran

University of Medical Science (Grant No. 48430) supported this work. The

authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during

the preparation of this manuscript.

References

1. Mirlekar B,

Pylayeva-Gupta YJC. IL-12 family cytokines in cancer and immunotherapy.

Cancers. 2021;13(2):167.

2. Deleuze A, Saout J,

Dugay F, Peyronnet B, Mathieu R, Verhoest G, et al. Immunotherapy in renal cell

carcinoma: the future is now. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2020;21(7):2532.

3. Inamura K. Renal cell

tumors: understanding their molecular pathological epidemiology and the 2016

WHO classification. International journal of molecular sciences.

2017;18(10):2195.

4. Carril-Ajuria L, Santos

M, Roldán-Romero JM, Rodriguez-Antona C, de Velasco GJC. Prognostic and

predictive value of PBRM1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel).

2019;12(1):16.

5. Braun DA, Bakouny Z,

Hirsch L, Flippot R, Van Allen EM, Wu CJ, et al. Beyond conventional

immune-checkpoint inhibition—novel immunotherapies for renal cell carcinoma.

Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2021;18(4):199-214.

6. Supabphol S, Li L,

Goedegebuure SP, Gillanders WE. Neoantigen vaccine platforms in clinical

development: understanding the future of personalized immunotherapy. Expert

opinion on investigational drugs. 2021;30(5):529-41.

7. Blum JS, Wearsch PA,

Cresswell P. Pathways of antigen processing. Annual review of immunology.

2013;31:443-73.

8. Morganti S, Tarantino

P, Ferraro E, D’Amico P, Duso BA, Curigliano GJTr, et al. Next generation

sequencing (NGS): a revolutionary technology in pharmacogenomics and

personalized medicine in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019:9-30.

9. Fang Y, Mo F, Shou J,

Wang H, Luo K, Zhang S, et al. A pan-cancer clinical study of personalized

neoantigen vaccine monotherapy in treating patients with various types of

advanced solid tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 2020;26(17):4511-20.

10. Hilf N, Kuttruff-Coqui

S, Frenzel K, Bukur V, Stevanović S, Gouttefangeas C, et al. Actively

personalized vaccination trial for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Nature.

2019;565(7738):240-5.

11. Keskin DB, Anandappa AJ,

Sun J, Tirosh I, Mathewson ND, Li S, et al. Neoantigen vaccine generates

intratumoral T cell responses in phase Ib glioblastoma trial. Nature.

2019;565(7738):234-9.

12. Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB,

Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine

for patients with melanoma. Nature. 2017;547(7662):217-21.

13. Ott PA, Hu-Lieskovan S,

Chmielowski B, Govindan R, Naing A, Bhardwaj N, et al. A phase Ib trial of

personalized neoantigen therapy plus anti-PD-1 in patients with advanced

melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, or bladder cancer. Cell.

2020;183(2):347-62. e24.

14. Blass E, Ott PA.

Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer

vaccines. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2021;18(4):215-29.

15. Peng M, Mo Y, Wang Y, Wu

P, Zhang Y, Xiong F, et al. Neoantigen vaccine: an emerging tumor

immunotherapy. Molecular Cancer. 2019;18:1-14.

16. Chong C, Coukos G,

Bassani-Sternberg MJNb. Identification of tumor antigens with

immunopeptidomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(2):175-88.

17. Braun D.A, Moranzoni G,

Chea V, McGregor BA,

Blass E,Tu CR. A neoantigen vaccine generates antitumor

immunity in renal cell carcinoma. Naturer. 2025;639: 474-482.

18. Li X, You J, Hong L, Liu

W, Guo P, Hao X. Neoantigen cancer vaccines: a new star on the horizon. Cancer

Biology & Medicine. 2024;21(4):274.

19. Wang J, Xi Z, Xi J,

Zhang H, Li J, Xia Y, et al. Somatic mutations in renal cell carcinomas from

Chinese patients revealed by whole exome sequencing. Cancer Cell International.

2018;18(1):1-12.

20. Wang Y, He P, Zhou X,

Wang C, Fu J, Zhang D, et al. Gene mutation profiling and clinical

significances in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clinics. 2023;78:100259.

21. Fritsch EF, Rajasagi M,

Ott PA, Brusic V, Hacohen N, Wu CJ. HLA-binding properties of tumor neoepitopes

in humans. Cancer immunology research. 2014;2(6):522-9.

22. Cho YH, Kim MS, Chung

HS, Hwang EC. Novel immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Investigative and Clinical Urology. 2017;58(4):220-7.

23. Sönmez MG, Sönmez LÖ.

New treatment modalities with vaccine therapy in renal cell carcinoma. Urology

Annals. 2019;11(2):119-25.

24. Amato RJ. Vaccine

therapy for renal cell carcinoma. Reviews in Urology. 2003;5(2):65.

25. Finn OJ. Human tumor

antigens, immunosurveillance, and cancer vaccines. Immunologic research.

2006;36:73-82.

26. Hole N, Stern P. A 72 kD

trophoblast glycoprotein defined by a monoclonal antibody. British journal of

cancer. 1988;57(3):239-46.

27. Rahma OE, Ashtar E,

Ibrahim R, Toubaji A, Gause B, Herrin VE, et al. A pilot clinical trial testing

mutant von Hippel-Lindau peptide as a novel immune therapy in metastatic renal

cell carcinoma. Journal of translational medicine. 2010;8:1-9.

28. Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ,

Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor

heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. New

England journal of medicine. 2012;366(10):883-92.

29. Razafinjatovo C.

Molecular Profiling of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcimoma and Targeted Therapy

Response: University of Zurich; 2017.

30. Fang Y, Mo F, Shou J,

Wang H, Luo K, Zhang S, et al. A pan-cancer clinical study of personalized

neoantigen vaccine monotherapy in treating patients with various types of

advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(17):4511-20.

31. Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB,

Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine

for patients with melanoma. nature. 2017;547(7662):217-21.

32. Ott PA, Hu-Lieskovan S,

Chmielowski B, Govindan R, Naing A, Bhardwaj N, et al. A phase Ib trial of

personalized neoantigen therapy plus anti-PD-1 in patients with advanced

melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, or bladder cancer. Cell.

2020;183(2):347-62. e24.

33. Hassanipour S, Namvar G,

Fathalipour M, Salehiniya HJB. The incidence of kidney cancer in Iran: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018;8(2).

34. Gottlich HC, Nabavizadeh

R, Dumbrava M, Pessoa RR, Mahmoud AM, Garg I, et al. Emerging Antibody-Drug

Conjugate Therapies and Targets for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Kidney

Cancer. 2023;7(1):161-72.

35. Beksac AT, Paulucci DJ,

Blum KA, Yadav SS, Sfakianos JP, Badani KK. Heterogeneity in renal cell

carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2017 Aug;35(8):507-515.

36. Paulucci DJ, Sfakianos

JP, Yadav SS, Badani KK. BAP1 is overexpressed in black compared with white

patients with Mx-M1 clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A report from the cancer

genome atlas. Urol Oncol. 2016 Jun;34(6):259.e9-259.e14.