Investigating the

relationship between anxiety and perceived stress with coping strategies

adopted in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic

Fatemeh Shabani 1, Seyedeh

Hajar Sharami 1*, Roya Faraji 1,

Habib Eslami-Kenarsari 2, Asiyeh Namazi 3

1 Reproductive Health Research Center, Department of

Obstetrics & Gynecology, Al-zahra Hospital, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2 Vice-Chancellorship

of Research and Technology, Guilan University of

Medical Science, Rasht, Iran

3 Midwifery Department, Rasht branch, Islamic Azad

University, Rasht, Iran

Corresponding Authors: Seyedeh

Hajar Sharami

* Email: sharami@gums.ac.ir

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has led to mental problems, including stress and

anxiety, for people, especially pregnant women. Identifying strategies to deal

with stress is important and can help pregnant mothers to adapt to stressful

life factors such as the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study

was designed and implemented with the aim of investigating the relationship

between anxiety and perceived- stress with the coping strategies of pregnant

women referring to Al-Zahra Hospital in Rasht.

Methods: The current study

was conducted on 221 pregnant women using a cross-sectional analysis method.

The required information was collected by the self-report method through

demographic questionnaires, Corona disease anxiety (CDAS), Cohen's perceived

stress, and Endler and Parker's coping strategies questionnaire. Data were

analyzed using SPSS version 22 software using Spearman's correlation

coefficient and linear regression tests. The significance level of the tests

was considered as P < 0.05.

Results: 53.4% of women had moderate anxiety and 60.6% of pregnant women had

high levels of perceived stress. There was a direct and significant correlation

between anxiety-perceived stress and emotion-focused strategy (P<0.001).

Conclusion: The present study showed high perceived stress and moderate anxiety in

pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic and their relationship with

emotion-focused coping strategies.

Keywords: Coping strategies, Anxiety, Perceived stress, Self-care, Coronavirus

Introduction

COVID-19

is a new respiratory disease that is spreading rapidly worldwide the world and

was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020

(1). In addition

to physical complications (2) and mortality,

the COVID-19 pandemic also causes psychological disorders in members of society

(3) and especially in pregnant women (4). The mental

health of women, especially pregnant women, is crucial due to their role in the

family. Studies have shown that during the COVID-19 pandemic, women are

experiencing higher rates of anxiety, depression, and stress compared to men (5-7). Due to

physiological and psychological changes during pregnancy, this period is one of

the most sensitive stages of a woman's life. These changes in pregnant women

lead to the induction of great changes, including physiological and

psychological changes, which cause the emergence of psychopathological

disorders, including stress and anxiety (8).

Mood and anxiety disorders are among the most

common problems during pregnancy, which is why half of pregnant women

experience pregnancy-specific anxiety (9). With the

Prevalence of infectious diseases, such as the stressful conditions during the COVID-19

pandemic and the changes created due to the existing conditions, widespread

anxiety disorders during pregnancy have intensified so that in pregnant women,

symptoms of anxiety (57%) and depression (37%) compared to the period before

Corona shows an increase (10, 11). Despite the

prevalence of corona disease, fear and stress in pregnant women due to the fear

of infection and transmission to the fetus have caused excessive and obvious

anxiety with negative psychological effects in this vulnerable group (12). Due to

physiological changes, these worries increase in the first and third trimester

compared to the second trimester (13, 14). During the COVID-19

pandemic, pregnant women in the first trimester reported increased stress at

work, increased stress from home, and greater feelings of anxiety than pregnant

women in the second and third trimesters. In addition, pregnant women in the

second trimester of pregnancy felt more helpless than pregnant women in the

first and third trimesters of pregnancy (13). The stress

hormone cortisol, along with the release of inflammatory markers like

cytokines, can lead to negative consequences for both mother and fetus due to

elevated levels of these chemicals (15).

The

negative effects of maternal anxiety and stress during pregnancy lead to

complications such as postpartum depression and mood disorders (16), preeclampsia,

pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting, increased blood pressure, and increased

number of unplanned cesarean section. Furthermore, due to the increase of

glucocorticoids, their negative effects on the fetus include weight loss,

increased fetal birth defects, infant mortality (17, 18), as well as

fetal and neonatal complications such as premature delivery (19, 20), low birth

weight, low Apgar score, neonatal abnormalities such as cleft palate,

hospitalization, and developmental delay. These babies often have symptoms such

as severe bloating and heart pain, insomnia at night, and constant crying (21-23). Although

studies show that fear and anxiety caused by the illness can increase

preventive behaviors in a person, fear and anxiety related to the disease are are directly related to psychological problems (9, 24). The World

Health Organization announced in 2014 that mental disorders in women not only

affect the individual, but also their children and other family members, and

thus the society, as well as future generations in economic planning (25).

Coping

is a person's first reaction to stressful events (26).

Interestingly, some research suggests that coping can also moderate the effects

of stress on mental health (27, 28). But many

studies indicate the relationship of coping strategies with mental health

consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic (9, 11, 23, 29,

30). Therefore, it

is important to identify stress coping strategies and it can help pregnant

mothers to adapt to the stressful factors of life, especially the existing

conditions affecting the COVID-19 disease. There are three types of coping

strategies: Problem-focused strategy, emotional-focused strategy, and avoidance

coping strategy (31, 32). In

Problem-focused strategy, the person tries to manage or modify the stressful

situation, and this type of coping is useful when faced with a controllable

stressor (33). People who

use problem-based coping reduce their stress levels by gathering available

information to deal with the stressor (18, 34). The more

problem-focused coping strategies a person uses, the better their mental health

and the less anxiety and worry they display, and vice versa. Problem-focused

coping strategies are associated with more coping, and emotion-focused coping

strategies are associated with less coping (35, 36). Avoidant and

emotion-focused coping strategies act as mediators through which experiences of

COVID-19 is indirectly related to mental health during pregnancy (9, 23).

Prior

to the COVID-19 pandemic, a study was conducted on a group of pregnant women

which revealed that avoidant coping strategies such as refusal,

non-involvement, and self-blame were associated with an increased risk of

mental health issues. On the other hand, emotion-focused coping strategies were

found to be less associated with mental health issues, while problem-focused

coping strategies were not found to be related to mental wellbeing issues. In a

recent study conducted on non-pregnant women prior to the outbreak, it was found

that maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance were associated with

increased levels of stress and anxiety. During outbreaks, these maladaptive

coping strategies were found to be associated with even higher levels of stress

and anxiety (8, 9, 29). It seems that

when faced with stressors that are beyond our control, utilizing

emotion-focused coping strategies proves to be more effective. On the other

hand, when dealing with situations that we have some level of control over,

employing problem-focused coping strategies tends to yield better results (37). The mental

health of pregnant women is a high-risk concern in society, especially during

stressful conditions such as the coronavirus pandemic. Effective interventions

can be taken to reduce stress by adopting coping strategies and eliminating

inappropriate solutions. By understanding the coping strategies adopted by

pregnant women in the face of perceived anxiety and stress, necessary

interventions can be implemented to improve their mental health. Due to the

scarcity of studies related to coping strategies during pregnancy, this study

aims to investigate the relationship between perceived anxiety and stress and

coping strategies adopted by pregnant women, highlighting the importance and

necessity of this topic.

Methods

This

cross-sectional analytical study was conducted after receiving the code of Guilan University of Medical Sciences from June to

September 2022 and with a random sampling of 221 pregnant women referred to the

educational-therapeutic center of Al-Zahra Hospital in Rasht. To be considered

for the study, patients must have singleton pregnancies, have ultrasound

confirmation at 8 weeks, basic literacy level or above, know the Persian

language, consent to participate in the application process, and meet certain

conditions such as substance abuse risk factors. Patients who have had physical

illness, undergone medical consultations or had experienced significant stress

in the last six months (such as a loved one's divorce or death), were not

willing to cooperate with others, and completed the questionnaire unfinished..

Method

of determining sample size

The

sample size was obtained using the study of Basharpoor

et al (38) and the study

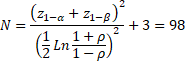

of Masjoudi et al (24) The initial

sample size was obtained from the following formula, but the questionnaires

were given to 256 pregnant women in this study.

![]()

Measures

1. Demographic

information questionnaire: personal, social, midwifery profile

questionnaire which is a questionnaire of 23 questions made by the researcher,

12 questions about age, education, occupation, level of education of spouse,

occupation of a spouse, number of pregnancies, history of abortion, amount of

income Household, residence status, covered by health insurance, current week

of pregnancy and additionally, there are 11 questions addressing potential risk

factors in the individual, including contact with a COVID-19 patient, smoking,

and hookah usage, among others.

2. COVID-19

Anxiety Scale (CDAS): This questionnaire was prepared and validated to

measure anxiety during the Corona era in Iran and has 18 items and 2 components

(factors) regarding anxiety. Items 1 to 9 measure psychological symptoms and

items 10 to 18 measure physical symptoms. The instrument is rated on a 4-degree

Likert scale (never = 0, sometimes = 1, most of the time = 2, and always = 3).

Therefore, the highest and lowest scores that respondents get in this

questionnaire are between 0 and 54. High scores indicate a high level of

anxiety in individuals. The total CDAS score was divided into 0–16 (mild),

17–29 (moderate), and 30–54 (severe). The reliability of this tool was obtained

using Cronbach’s alpha method for the cause of psychological symptoms (0.879)

and physical symptoms (0.861) of the total questionnaire (0.919) (39).

3.

Cohen's Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): 14-item version was used in this research. This scale is a

self-report tool consisting of 14 items that was developed by Cohen, Kamarck & and Mermelstein in 1983 in order to know how

individuals evaluate their difficult and exhausting experiences. In this scale,

individuals are asked to indicate on a five-point scale from 0 (never) to 4

(very much) how they often felt during the last 10 weeks. In this scale, after

reverse scoring the items 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13, a total score is obtained

by summing up the scores of all items for each person. On this scale, the

minimum and maximum scores are 0 to 56. The higher the score, the higher the

score. It means more perceived stress. In the study of Cohen et al. (1983), the

internal consistency coefficients for each of the subscales and the overall

score were between 0.84 and 0.86 (40). This

questionnaire was developed in Iran by Safaei and Shokri. , with the

translation and construct validity and convergent validity being confirmed.

Furthermore, the reliability of the survey was assessed and found to be

appropriate, with a value of 0.84 (41).

"4.

"Endler" and "Parker" Coping Strategies Questionnaire: The Coping

Strategies Questionnaire developed by Endler and Parker (1990) is comprised of

45 items that utilize the Likert method to determine responses ranging from

never (1) to always (5). The questionnaire is divided into three main areas of

coping behaviors, with each area containing 15 questions. These areas include

problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and avoidant coping.

Problem-focused coping involves actively managing and solving the problem,

while emotion-focused coping focuses on emotional responses to the problem, and

avoidant coping involves running away from the problem. The scoring system for

this questionnaire is based on a 5-point Likert scale, with a maximum score of

5 and a minimum score of 1 for each subject. The score for each of the three

coping behaviors ranges from 15 to 75, with the behavior that receives the

highest score being considered the person's primary coping strategy. The total

score for the coping strategy ranges from 45 to 225 (42). Qureshi Rad et al. conducted the validation of this scale,

yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.84 and Cronbach's alpha of 0.83 for the

overall scale. Additionally, the subscales of problem-focused, emotion-focused,

avoidance, and social orientation demonstrated correlation coefficients of

0.86, 0.81, 0.79, and 0.69, respectively. The coping strategy in this study was

operationally defined as the total score obtained by individuals participating

in the study, based on their responses to the Andler and Parker coping

strategies questionnaire (43).

Data

analysis

In

this research, a total of 256 pregnant women were selected to participate by

completing questionnaires. However, three individuals declined to continue

their cooperation, resulting in a final sample size of 253 participants. Among

the remaining participants, 23 reported having an underlying disease, and nine

experienced significant stressful events within the past six months. These

individuals were excluded from the study, leaving a final analysis sample of

221 pregnant women. For data analysis, the researchers utilized SPSS-22

software. Descriptive statistics methods were employed to analyze the data,

including the use of frequency and percentage distribution tables for

qualitative variables. Additionally, quantitative variables were analyzed using

measures such as standard deviation, average, minimum, and maximum. To examine

the relationship between variables, Spearman's correlation coefficient tests

were conducted. Furthermore, to account for any confounding factors, the

researchers employed the multivariable linear regression method. The

significance level for all tests was set at 5%.

Results

Table

1 presents the demographic characteristics information of the participants.

Based on the data provided, the average age of pregnant women was 30.96 years,

with a standard deviation of 11.64. The age range varied from 18 to 44 years.

The gestational age ranged from 8 to 39 weeks. The number of pregnancies for

women ranged from 1 to 5, and the average gestational age was 26.62 with a

standard deviation of 8.87. A majority of the women (57.5%) held a diploma,

while 86% were housewives. Additionally, 67.4% of the participants had an

average household income between 2 and 5 million Tomans (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants’ demographic and

obstetrics characteristics (Frequency distribution of quantitative and

qualitative variables).

|

variables |

M±SD |

Maximum-minimum |

|

Age |

30.96±11.64 |

18-14 |

|

Gravida |

1.95±1.21 |

1-5 |

|

number of children |

0.57±0.75 |

0-3 |

|

Number of abortions |

0.35±0.75 |

0-5 |

|

Gestational age (weeks) |

26.62±8.87 |

8-39 |

|

variables |

|

Frequency(%) |

|

Mother’s Educational status |

|

|

|

Secondary school |

|

33(14.9) |

|

Diploma |

|

127(57.5) |

|

University |

|

61(27.6) |

|

Mother’s Employment status |

|

|

|

Housewife |

|

190(86) |

|

Self-employed |

|

12(5.4) |

|

Employed |

|

19(8.6) |

|

Spouse’s Educational status |

|

|

|

Secondary school |

|

42(19) |

|

Diploma |

|

119(53.8) |

|

University |

|

60(27.2) |

|

Spouse’s Employment status |

|

|

|

Self-employed |

|

147(66.5) |

|

Worker |

|

35(15.8) |

|

Employed |

|

30(13.6) |

|

Farmer |

|

9(4.1) |

|

Income |

|

|

|

≥ 20000000 rail |

|

36(16.3) |

|

20000000-50000000 rail |

|

149(67.4) |

|

≥50000000 rail |

|

36(16.3) |

The

mean (standard deviation) of the anxiety score and perceived stress score were

(16.57±7.16) and (31.06±8.64), respectively. The mean (standard deviation)

score of Problem-focused strategy,

Emotional-focused strategy, and avoidant coping strategy were (49.95±9.32),

(44.53±12.41) and (43.06±8.99) respectively. The minimum and maximum anxiety

score was 5-44, and the minimum and maximum perceived stress score was 13-56.

In addition, the minimum and maximum score of the total coping strategy was

59-192, the minimum and maximum score of the Problem-focused strategy was

21-70, the Emotional-focused strategy was 17-67, and the Avoidant coping

strategy was 21-68 (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation of

different dimensions of anxiety, perceived stress and adopted coping

strategies.

|

Variable |

kurtosis |

Skewness |

SD |

mean |

Min-max |

|

anxiety |

1.222 |

1.009 |

7.16 |

16.57 |

5-44 |

|

Perceived Stress |

-0.239 |

0.191 |

8.64 |

31.06 |

13-56 |

|

coping strategy |

0.111 |

-0.105 |

21.36 |

137.55 |

59-192 |

|

Problem-focused strategy |

-0.375 |

-0.169 |

9.32 |

49.95 |

21-70 |

|

Emotional-focused strategy |

-0.869 |

-0.142 |

12.41 |

44.53 |

17-67 |

|

Avoidant coping strategy |

0.176 |

0.320 |

8.99 |

43.06 |

21-68 |

Initial findings additionally indicated that 118 individuals

(60.6%) experienced mild anxiety, while 89 participants (40.3%) reported

moderate anxiety, and 14 individuals (6.3%) suffered from severe anxiety as a

result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the assessment of perceived stress

revealed that 134 pregnant women (60.6%) exhibited elevated levels of stress.

In terms of coping strategies, 121 individuals (54.8%) employed problem-focused

coping, 79 individuals (35.7%) utilized emotion-focused coping, and 21

individuals (9.5%) resorted to avoidance coping (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency of anxiety, perceived stress and stress and adopted

coping strategies.

|

% |

Frequency |

Level |

Variable |

|

|

|

|

Anxiety |

|

53.4% |

118 |

mild |

|

|

40.3% |

89 |

moderate |

|

|

6.3% |

14 |

severe |

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived

stress |

|

39.4% |

87 |

low |

|

|

60.6% |

134 |

high |

|

|

Coping

strategy |

|||

|

54.8% |

121 |

|

Problem-focused

strategies |

|

35.7% |

79 |

|

emotional-focused

strategies |

|

9.5% |

21 |

|

Avoidance

strategies |

The results show that there is a direct and significant linear

correlation between anxiety and the adopted coping strategies (r=0.263); also

the perceived stress and the adopted coping strategies (r=0.309)

(P-value=0.001>) in Meanwhile, there is a direct and significant linear

correlation between anxiety and emotion-focused coping strategy (r=0.413) and

between perceived stress and emotion-focused coping strategy (r=0.408)

(P-value=0.001). However, there is a direct linear correlation between anxiety

with avoidance coping strategy (r=0.183) (P-value=0.006) and between perceived

stress with avoidance coping strategy (r=0.169) (P-value=0.012). Also, there is

no direct and significant linear correlation between anxiety with

problem-focused strategies (r=-0.119) (P-value=0.078) and There is no direct

and significant linear correlation between perceived stress and problem-focused

strategies (r=-0.008) (P-value=0.906) (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation between anxiety and perceived stress with adopted

coping strategies.

|

Avoidance strategies |

emotional-focused strategies |

Problem-focused strategies |

coping strategy |

Statistical tests |

|

|

|

|

|

Anxiety |

|

0.183 |

0.413 |

-0.119 |

0.263 |

Spearman

correlation coefficient |

|

0.006 |

0.001> |

0.078 |

0001> |

P-value |

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived

stress |

|

0.169 |

0.408 |

-0.008 |

0.309 |

Spearman

correlation coefficient |

|

0.012 |

0.001> |

0.906 |

0.001> |

P-value |

The results of linear regression show that with the increase of

each unit in the emotion- focused strategy score, the anxiety score increases

by 0.4 or 40%, provided that other factors are constant. In the variable of

anxiety, the squared multiple correlation coefficient (R2 variable coefficient)

equal to 0.167 shows that the predicting variables of triple strategies predict

16.7% of the variance of anxiety scores of pregnant women. Also, the results of

multiple linear regression show that with the increase of each unit in the

emotion-focused strategy score, the perceived stress score increases by 0.39 or

39%, provided that other factors are constant. In the stress variable, the

squared multiple correlation coefficient (R2 variable coefficient) equal to

0.147 shows that the predicting variables of the triple strategies predict

14.7% of the variance of the stress scores of pregnant women (Table 5).