Frequency of adult

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in outpatient psychiatric

clinic, Babol University of Medical Sciences

Sakineh Javadian 1, Seyedeh Maryam

Zavarmosavi 2, Mohsen Ashrafi 3, Hemmat Gholinia 4,

Armon Massoodi 5 *

1 Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Social

Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol

University of Medical Sciences

2 Department

of Psychiatry, Shafa Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht,

Iran

3 Student Research Committee, Babol University of

Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

4 Health Research Institute, Babol University of

Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

5 Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health

Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

Corresponding Authors: Armon

Massoodi

* Email: armonmassoodi@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adulthood is

associated with significant impairment in occupational, academic, and social

functioning. The aim of this study is to survey the frequency of ADHD in adults

referred to psychiatric clinics.

Methods: The present

cross-sectional descriptive study includes 300 patients referred to psychiatric

clinics affiliated to Babol University of Medical Sciences with an age range of

18-45 years who were selected and included in the study. It is used the adults

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder self-report scale (ASRS V1.1) to

diagnose Adult ADHD in these individuals. Logistic regression and P-Paired test

were used to analyze the data.

Results: The mean age of the subjects was 30.21 ± 7 7.94. Of these, 181 (60.3%)

were men and 119 (39.7%) were women. The overall prevalence of Adult ADHD in

the study samples was 39.3%. In the logistic regression analysis of crude and

adjusted data of study variables, no significant relationship was seen between

Adult ADHD and age, education, employment status and marital status (P ≥ 0.05),

but a significant relationship between Adult ADHD and consumption of

Cigarettes, alcohol and drugs were observed (P ≤ 0.05).

Conclusion: The findings of the present study show a relatively high prevalence of

Adult ADHD among people with a history of psychiatric disorder, who are more

likely to be exposed to smoking, alcohol and drug abuse.

Keywords: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Mental Disorder, Adult

Introduction

Adult

ADHD is a type of psychiatric disorder that often appears in childhood. It is

characterized by a stable pattern of attention deficit, hyperactivity, and

impulsive behaviors (1). Impulsive behaviors are performed momentarily, without

thinking about their results and without analyzing and evaluating positive and

negative achievements. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is known as a

childhood disorder that can be improved with supervision and treatment, but

many sources have shown that ADHD is stable in adulthood and difficult to treat

(2,3). Executive functions that may be abnormal in adults with ADHD include

working memory, task switching, self-monitoring, initiation, and self-control.

These deficits are related to the attention deficit. Characterize Adult ADHD

problems: concentrating on a specific task, especially for long periods,

organizing activities, prioritizing tasks, following up and completing tasks,

forgetfulness, time management (as example of missing an appointment) (4).

Adults with Adult ADHD often report that things only get done at the last

minute, often late or not at all. An increase in driving-related problems,

including an increase in driving errors, traffic fines, and speeding, may be

related to attention deficits (5).

Adults

with ADHD have higher rates of employment problems, criminal activity,

substance abuse problems, accidents, and vehicular referrals compared to adults

without ADHD. It is believed that ADHD-related disorders from childhood such as

academic problems, self-esteem problems significantly in family and peer

relationships underlie these behavioral problems in adulthood (6). Mortality

rates were higher than in people with ADHD compared to people without ADHD in a

study in 2015 using Danish national registry data, with accidents being the

most common cause of death in people with ADHD (7).

ADHD

is a common disorder among young people worldwide. In a study in 2007, a

meta-analysis of more than 100 studies estimated the prevalence of ADHD in

children and adolescents worldwide at 5.3% (8). Simon et al., found the

prevalence of ADHD to be 2.5% in adults based on a meta-analysis of six studies

(9). Prospective longitudinal studies support the theory that approximately

two-thirds of adolescents with ADHD retain symptoms of the disorder into

adulthood (10). Recent changes in the new DSM-5 diagnostic criteria have

increased the prevalence of ADHD, which is less significant for children but

has likely had a significant impact on diagnosis rates in adults (11, 12). In a

World Health Organization survey, among respondents aged 18 to 44 in ten

countries in the Americas, Europe, and the Middle East, the current prevalence

of ADHD in adults was assessed 3.4%, which was 1.9% in low-income countries and

4.2% in high-income countries (13).

ADHD

is associated with a number of psychiatric illnesses. It has been reported that

approximately 80% of adult ADHD patients have at least one lifelong psychiatric

illness in adults. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common

comorbidity (prevalence 24.4 to 31%) (14). Anxiety disorders are also a common

disease of adult ADHD patients. In the general population, the prevalence of

any anxiety disorder approaches 20%, while this figure increases to 47% in

adults with Adult ADHD (15). In addition, 65% of adult patients with adult ADHD

and concurrent bipolar disorder have a history of at least one anxiety disorder

during their lifetime (16). Substance abuse is another common comorbidity seen

in adult ADHD patients, who may use alcohol, drugs, and nicotine as a form of

self-medication (17). It has been estimated that approximately one-fourth of

people with substance use disorder (SUD) have co-occurring ADHD, and in

addition, they have a worse treatment prognosis compared to substance abusers

without adult ADHD (18). There is evidence that ADHD treatment in childhood or

adolescence may reduce the severity and course of substance use disorders in

adulthood (19).

Perhaps

the most serious aspect of ADHD lies in its tendency to be associated with

disorders, some of which affect not only behavior but also personality. This

not only endangers the well-being and life of ADHD sufferers but also their

social environment. These comorbidities are seen in children and if not

resolved in late puberty, they can turn into personality disorders such as

antisocial personality disorder or continue as extroversion disorders until

adulthood (20). Sleep disorders are another comorbidity that affects children

with ADHD at a much higher level than developing children (21). In addition,

these sleep disturbances can exacerbate ADHD symptoms such as inattention and

motor dysfunction even more (22).

Vnukova

et al., in 2020 conducted a study in the Czech population to investigate the

prevalence of ADHD among adults. It was observed that 119 (7.84%) of 1518

people were diagnosed with ADHD based on the ASRS questionnaire. Also, the rate

of ADHD was higher in men than in women. The age of subjects was also related

to ASRS score (23). In 2018, Valsecchi et al conducted a study to determine the

prevalence and clinical correlates of Adult ADHD in a sample of psychiatric

outpatients. Their study included 634 outpatients and they used the ASRS

questionnaire and DIVA specialized calculator to diagnose ADHD. The findings of

the study showed that 12.8% of people were considered ADHD-positive in the ASRS

questionnaire and 6.9% of people based on the DIVA specialized interview (24).

According to the mentioned issues, Adult ADHD has a great psychological and

social burden for the individual and society. On the other hand, due to the

relationship between Adult ADHD and various comorbidities, it is possible to

reduce the psychological and social burden of the disease in people who go to

the doctor because of other psychiatric disorders. In addition, due to its

relatively high prevalence in adults and the fact that in many children, the

symptoms continue until adulthood, and in the adult period, less importance is

given to its diagnosis and treatment, and this issue can have many consequences

for the affected person, his/her family and the community and cause problems

such as job problems, marital problems and delinquency. The present study aims

to investigate the frequency of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

(Adult ADHD) in outpatients of the psychiatric clinic of Babol University of

Medical Sciences.

Methods

The

current descriptive-cross-sectional study was conducted with the aim of

investigating the frequency of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

(Adult ADHD) in the outpatients of the psychiatric clinic of Babol University

of Medical Sciences. The research samples were selected using available

sampling method, including 300 patients who visited the psychiatric clinics of

Babol University of Medical Sciences as outpatients in the period of autumn

2019. Inclusion criteria include the age range of 18 to 45 years, absence of

severe mental disability and psychotic disorder, cognitive impairment,

willingness and consent to participate in the study. The only exclusion

criterion of the study includes unwillingness to continue cooperating in the

study.

Sample

volume calculation formula:

n =

sample size = 300

(1)

(1)

In

relationship (1)

α =

0.05

p

=0.1

d

=0.025

z =

percentage of standard error of the acceptable confidence factor

p =

proportion of the population with a given trait

q=1-p

A proportion of the population without a certain trait

α=

degree of confidence or desired possible accuracy

d=

maximum sampling accuracy

Sampling

and distribution of the questionnaire was done after obtaining permission from

the Vice-Chancellor of Research and obtaining a research permit and code of

ethics IR.MUBABOL.REC.1399.242 and obtaining permission from the responsible

director and head of the psychiatric clinic of Babol University of Medical

Sciences and explaining the research objectives to them. The questionnaires

were completed by the researcher himself, and in order to preserve the

confidentiality of the information of the research samples, the questionnaires

were without names. The reason for using this method is that if the samples had

problems in understanding the sentences of the questionnaire, sufficient

explanations would be given to them. First, the research samples were talked to

and the necessary explanations were given to these people about the research,

its necessity and benefits.

Then,

if they were satisfied and completed the written consent form, they answered

the study questionnaires. In the present study, there are two questionnaires,

in which form number 1 deals with the demographic characteristics of the

individual, and in form number 2, all patients completed the self-report

questionnaire of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ASRS-v.1.1).

Demographic

information including age, sex, occupation, education, as well as clinical

records such as physical illness records, psychiatric illness and

hospitalization records, history of referral or treatment for ADHD in

childhood, duration of drug use, type of drug used were collected from all

patients. The Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale

(ASRS-v.1.1) was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and a working

group consisting of teams of psychiatrists and researchers from the World

Health Organization. ASRS scale questions are consistent with DSM-5 criteria.

This scale includes two dimensions and 18 questions, which are divided into two

parts, A and B. There are 9 questions for the dimension of inattention and 9 questions

for the dimension of hyperactivity/impulsivity. Research questions are scored

on a 5-point Likert scale from never (1 point) to almost always (5 points). In

a study conducted in Iran by Mokhtari et al., the reliability of the

questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha method was 87%. Also, the sensitivity of

this questionnaire with a cut-off point of 50 for diagnosing ADHD in adults is

70% and the specificity of this questionnaire is 99% (25).

After

completing the questionnaires by the research samples, the score of the ASRS

questionnaire is calculated and people with a score less than 50 are considered

not suffering from Adult ADHD, and people with a score of 50 and above are

considered suffering from Adult ADHD.

The

resulting data were entered into SPSS statistical software version 24 and

evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively. The significant level of the test

will be less than 0.05 (p<0.05). P-Paired and Chi-square statistical tests

were used to analyze the data.

Results

This

cross-sectional study was conducted on 300 people who referred to psychiatric

clinics affiliated to Babol University of Medical Sciences to determine the

frequency of Adult ADHD in adults. All the study samples have answered the

answer letters completely and are in accordance with the entry and exit

criteria of the study. For this reason, we did not have a sample excluded from

the study.

The

average age of the subjects was 30.21 years with a standard deviation of 7.94.

181 cases (60.3%) were men and 119 cases (39.7%) were women. 43 cases (14.3%)

had a bachelor's degree, 103 cases (34.3%) had diploma education and 154 cases

(51.3%) had higher education. 214 cases (71.3%) were employed and the rest were

unemployed, 157 cases (52.3%) were single and 143 cases (47.7%) were married.

In addition, 51 cases (17%) had a history of using at least one of tobacco,

alcohol or drugs. In connection with the use of the mentioned items, 49 cases

(16.3%) used tobacco, 17 cases (5.7%) used alcohol, and 15 cases (5%) also used

drugs.

Logistic

regression analysis was used to investigate adult ADHD and risk factors

affecting it. People with a score of 50 and above were considered to have Adult

ADHD and people with a score below 50 were considered not to have Adult ADHD.

Also, the average adult ADHD score of people in general was 46.7 with a

standard deviation of 11.08 and 118 people (39.3%) had adult ADHD and 182

people (60.7%) did not have adult ADHD.

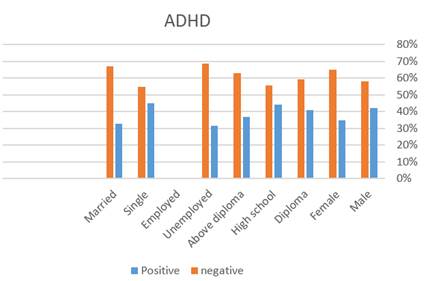

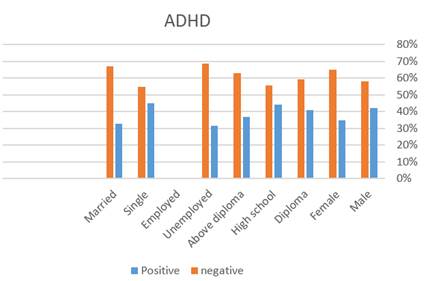

The

findings related to data analysis and their relationship with adult ADHD are

given in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Figure

1: Review of risk factors related to Adult ADHD.

Discussion and Conclusion

The

data obtained from the present study show the prevalence of Adult ADHD in

psychiatric clinic outpatients at 39.3%. The prevalence rate obtained in the

present study is higher than in similar studies. In a study conducted by

Valsecchi et al. on Italian psychiatric outpatients, the overall prevalence of

adult ADHD was reported as 6.9% (24). In order to evaluate patients with Adult

ADHD, they subjected the patients who were diagnosed with Adult ADHD in the

ASRS-V1.1 questionnaire to a specialized interview. So, patients were screened

more intensively than using a questionnaire alone.

In

other community-based studies, the observed prevalence is lower than in the

present study. Polyzoi et al., and 2018 (26) On a Swedish population, the

prevalence rate in people aged 18 years and older was estimated to be 3.54 per

1000 people. Vňuková et al., in 2021 (23). In the Czech Republic, the

prevalence of Adult ADHD was assessed as 7.84% based on the 6-item ASRS

questionnaire. On the other hand, the 6-item ASRS questionnaire shows that the

reported rate is lower than the actual level (27), for this reason, the

predicted prevalence in this study was evaluated as 14%. De Zwaan et al., in

2012, the raw prevalence rate of ADHD was evaluated as 4.7% (28).

Ghoreishizadeh et al., in 2014, the prevalence rate in adults aged 18-45 years

was evaluated as 3.8% (29).

The

relatively high prevalence of observation in the present study can have various

reasons. The people who entered the study were selected as available and from

the population with psychiatric disorders. On the other hand, in a random

sample of people who have a psychiatric illness, they may have a high

percentage of Adult ADHD. According to the studies, Adult ADHD can be

associated with other psychiatric diseases such as substance use disorder, mood

disorders (such as depression and bipolar disorder) and anxiety disorders. ADHD

and dysthymic disorder/depression are commonly associated, and the prevalence

of depression in individuals with ADHD varies from 18.6% to 53.3% in different

studies (30, 31). Similarly, studies have reported comorbid ADHD in individuals

with depression at rates of 9% to 16% (32), with an average incidence of 7.8% (33).

The risk of anxiety disorders in people with ADHD is higher than in the general

population, approaching 50% (28). Probably the most common comorbidity with

ADHD is substance use disorder (SUD), especially alcohol or nicotine, cannabis,

and cocaine (34).

Reports

indicate that personality disorders are present in more than 50% of adults with

Adult ADHD, usually cluster B and C personality disorders, and 25% of

individuals have two or more personality disorders (35).

Also,

there are studies showing the relationship between ADHD and bipolar disorder (36),

sleep disorders (21), obesity (37), Internet addiction, virtual networks and

video games (38). In other studies that have been conducted on adults with

Adult ADHD, the age limit was 18 years and above, which also included the

elderly, based on previous studies, with increasing age, especially in old age,

the rate of adult ADHD decreases, while in the present study, the upper age

limit of the people who entered the study was 45 years. Also, the average age

of the people included in the present study was lower compared to the reviewed

studies (20,21,39). The error in the answer should also be taken into account.

In

the present study, the prevalence of adult ADHD was not statistically related

to the age of the subjects. While in the study of Valsecchi et al., (24) in

2021, people with Adult ADHD were younger than people without Adult ADHD. Also,

in a study, De zwaan et al. reported a decrease in the prevalence of ADHD with

increasing age. However, De Zwaan et al., (29) observed a significant

difference between the age groups of 18 to 24 years and 55 to 64 years, while

the other age groups did not have a significant difference, which is similar to

the age group of present study (28).

In

the present study, there was no correlation between the prevalence of adult

ADHD and gender. There is evidence that shows that the rate of ADHD in boys is

2 to 3 times higher than that of girls, but in adults, this ratio tends to

equalize in the studies conducted (24). Also, in the study of Polyzoi et al.,

similar findings were observed with the present study, and no difference was

observed in the incidence of Adult ADHD between men and women (26). On the

other hand, a study conducted by Zetterqvist et al., (24) showed a higher

prevalence in adult men. Because Zetterqvist's study was conducted between 2006

and 2009, it can be concluded that the proportion of women with adult ADHD has

increased over time.

However,

these results do not mean that the graduate education level is a protective

factor against Adult ADHD. Various studies show a moderate association between

IQ and attention deficits (40), and the diagnosis of ADHD has the same validity

among children with high IQ and children with average IQ. It can be concluded

that people diagnosed with Adult ADHD who have a high level of education

compensate for their functional deficit due to ADHD with a lower IQ compared to

their peers.

In

the present study, a significant relationship between drug use and adult ADHD

was observed, and 56.9% of people who use drugs have adult ADHD. This finding

is expected, as ADHD is typically associated with risky behaviors and

decision-making problems (41). The present finding has also been shown in

various studies (24, 28, 42) In descriptive reports and demographic studies,

adult ADHD patients have described marijuana as helpful in controlling

inattention and impulsivity (43, 44). In a study conducted by Notzon et al.

(45), the prevalence of marijuana use was estimated at 34-46%. ROMO et al. also

observed a higher rate of marijuana use, alcohol use, and gambling in people

with Adult ADHD (46).

In

examining the relationship between marital status and adult ADHD, our findings

did not show a significant relationship, which is consistent with the

observations of Valsecchi et al. (24). But they observed that most people with

Adult ADHD are single and less likely to have a partner. In some previous

studies, no significant relationship between marital status and adult ADHD has

been observed (2, 13, 29). Some studies show that the prevalence of Adult ADHD

is higher in divorced people (15, 47). Also, in another study, the prevalence

of Adult ADHD was higher in widowed, divorced and single people (48). But,

considering the effect of Adult ADHD in adults and in their intimate

relationships, which leads to less stability and higher divorce rates, judging

the impact of this disorder on marital status may require longer follow-ups. In

the investigation of being employed, no significant relationship between being

employed and Adult ADHD was observed, as some studies had similar results (24,

28). While other studies have shown a higher prevalence of Adult ADHD in

unemployed people (15, 48).

The

main limitation of the present study is the absence of a secondary follow-up

for the additional examination of people who are diagnosed with Adult ADHD in

the ASRS-v1.1 questionnaire due to the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine

restrictions, as well as the lack of cooperation of the patients in the

circumstances. Considering the high prevalence that was observed, maybe a more

detailed investigation by dedicated interviews could have brought us more

accurate results. For example, Valsecchi et al. (24) subjected patients who

scored above 50 in the ASRS-v1.1 questionnaire to a dedicated DIVA interview.

The next limitation is the insufficient sample size, which may have caused the

variables related to Adult ADHD to not be evaluated correctly. On the other hand,

we did not have any information about the underlying disease and the history of

ADHD or ADHD symptoms in the childhood of these people. The findings of the

present study show that the prevalence of Adult ADHD is high among patients who

refer to the Babol Psychiatric Clinic as an outpatient. This shows the

importance of using appropriate screening methods in these people, early

diagnosis and treatment. Also, people who have a history of using tobacco

and/or alcohol and/or especially drugs, or are currently using them, should be

screened for Adult ADHD so that we can prevent more problems for them with

early diagnosis.

Authors contributions

SJ conceived and

designed the analysis, SMZ collected the data, MA contributed

data or analysis tools, HGh wrote the paper, AM performed the

analysis.

References

1.

Kaisari P., Dourish C.T.,

Higgs S. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and disordered eating

behaviour: A systematic review and a framework for future research. Clinical

psychology review, 2017; 53:109-21.

2.

De Graaf R., Kessler R.C.,

Fayyad J., Ten H. M., Alonso J., Angermeyer M. The prevalence and effects of

adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the performance of

workers: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Occupational

and environmental medicine, 2008; 65(12):835-42.

3.

Amira H., Mohammed Hala A.,

Abdel G., Ahmed M.M.M. Gross motor development in Egyptian preschool children

with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Pilot study. Journal of Advanced

Pharmacy Education & Research, 2017; 7(4): 438- 442.

4.

Barkley, R. A. Executive

functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. The Guilford

Press; 2012.

5.

Barkley R.A., Fischer M.,

Smallish L., Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive

functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American academy of child

& adolescent psychiatry. 2006; 45(2):192-202.

6.

Barkley R.A., Cox D. A

review of driving risks and impairments associated with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effects of stimulant

medication on driving performance. Journal of safety research. 2007;

38(1):113-28.

7.

Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD,

Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, Pedersen MG. Mortality in children, adolescents, and

adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort

study. The Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-6.

8.

Polanczyk G., Maurício

S.L., Bernardo L. H., Joseph B., Luis A. R. The Worldwide Prevalence of ADHD: A

Systematic Review and Metaregression Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry,

2007;164(6):942-8.

9.

Simon V., Czobor P., Bálint

S., Mészáros A., Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry.

2009;194(3):204-11.

10.

Faraone S.V., Biederman J.,

Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:

a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological medicine, 2006;

36(2):159-65.

11.

Polanczyk G., Caspi A.,

Houts R., Kollins S.H., Rohde L.A., Moffitt T.E. Implications of extending the

ADHD age-of-onset criterion to age 12: results from a prospectively studied

birth cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry,

2010; 49(3):210-6.

12.

Matte B., Anselmi L., Salum

G., Kieling C., Gonçalves H., Menezes A. ADHD in DSM-5: a field trial in a

large, representative sample of 18-to 19-year-old adults. Psychological

medicine. 2015; 45 (2):361-73.

13.

Fayyad J., De Graaf R.,

Kessler R., Alonso J., Angermeyer M., Demyttenaere K. Cross-national prevalence

and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The British

Journal of Psychiatry, 2007;190(5):402-9.

14.

Fischer A.G., Bau C.H.,

Grevet E.H., Salgado C.A., Victor M.M., Kalil K.L.. The role of comorbid major

depressive disorder in the clinical presentation of adult ADHD. Journal of

psychiatric research, 2007;41(12):991-6.

15.

Kessler R.C., Adler L.,

Barkley R., Biederman J., Conners C.K., Demler O. The prevalence and correlates

of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity

Survey Replication. American Journal of psychiatry, 2006; 163(4):716-23.

16.

Tamam L., Karakus G.,

Ozpoyraz N. Comorbidity of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and

bipolar disorder: prevalence and clinical correlates. European archives of

psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 2008; 258:385-93.

17.

Ohlmeier M.D., Peters K.,

Kordon A., Seifert J., Wildt B.T., Wiese B. Nicotine and alcohol dependence in

patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Alcohol

& Alcoholism, 2007; 42(6):539-43.

18.

Dom G., Moggi F.

Co-occurring addictive and psychiatric disorders: Springer; 2016.

19.

Groenman A.P., Oosterlaan

J., Rommelse N.N., Franke B., Greven C.U., Hoekstra P.J.Stimulant treatment for

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and risk of developing substance use

disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2013;203(2):112-9.

20.

Silva D., Houghton S.,

Hagemann E., Jacoby P., Jongeling B., Bower C. Child attention deficit

hyperactive disorder co morbidities on family stress: effect of medication.

Community mental health journal, 2015;51:347-53.

21.

Cortese S., Faraone S.V.,

Konofal E., Lecendreux M. Sleep in children with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of subjective and

objective studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry, 2009; 48(9):894-908.

22.

Schneider H.E., Lam J.C.,

Mahone E.M. Sleep disturbance and neuropsychological function in young children

with ADHD. Child Neuropsychology, 2016; 22(4):493-506.

23.

Vňuková M., Ptáček R.,

Děchtěrenko F., Weissenberger S., Ptáčková H., Braaten E. Prevalence of ADHD

symptomatology in adult population in the Czech Republic–A National Study.

Journal of Attention Disorders. 2021; 25(12):1657-64.

24.

Valsecchi P., Nibbio G.,

Rosa J., Tamussi E., Turrina C., Sacchetti E. Adult ADHD: prevalence and

clinical correlates in a sample of Italian psychiatric outpatients. Journal of

Attention Disorders, 2021; 25(4):530-9.

25.

Mokhtari H., Rabiei M.,

Salimi S.H. Psychometric properties of the persian version of adult

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report scale. Iranian Journal of

Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 2015; 21(3):244-53.

26.

Polyzoi M., Ahnemark E.,

Medin E., Ginsberg Y. Estimated prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD and

health care utilization in adults in Sweden–a longitudinal population-based

register study. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 2018:1149-61.

27.

Kessler RC, Adler LA,

Gruber MJ, Sarawate CA, Spencer T, Van Brunt DL. Validity of the World Health

Organization Adult ADHD Self‐Report Scale (ASRS) Screener in a representative

sample of health plan members. International journal of methods in psychiatric

research, 2007; 16(2):52-65.

28.

De Zwaan M., Gruss B.,

Müller A., Graap H., Martin A., Glaesmer H. The estimated prevalence and

correlates of adult ADHD in a German community sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin

Neurosci, 2012; 262(1):79-86.

29.

Amiri S., Ghoreishizadeh

M.A., Sadeghi-Bazargani H., Jonggoo M., Golmirzaei J., Abdi S. Prevalence of

adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Adult ADHD): tabriz. Iranian

journal of psychiatry, 2014; 9(2):83.

30.

Torgersen T., Gjervan B.,

Rasmussen K. ADHD in adults: a study of clinical characteristics, impairment

and comorbidity. Nordic journal of psychiatry, 2006; 60(1):38-43.

31.

Research APADo. Highlights

of changes from dsm-iv to dsm-5: Somatic symptom and related disorders. Focus,

2013;11(4):525-7.

32.

McIntosh D., Kutcher S.,

Binder C., Levitt A., Fallu A., Rosenbluth M. Adult ADHD and comorbid

depression: a consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD. Neuropsychiatric

disease and treatment, 2009:137-50.

33.

Bond D.J., Hadjipavlou G.,

Lam R.W., McIntyre R.S., Beaulieu S., Schaffer A. The Canadian Network for Mood

and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management

of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 2012; 24(1):23-37.

34.

Klassen L., Bilkey T.,

Katzman M., Chokka P. Comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and

substance use disorder: treatment considerations. Current drug abuse reviews,

2012; 5(3):190-8.

35.

Olsen J.L., Reimherr F.W.,

Marchant B.K., Wender P.H., Robison R.J. The effect of personality disorder

symptoms on response to treatment with methylphenidate transdermal system in

adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The Primary Care Companion

for CNS Disorders, 2012;14(5):26293.

36.

Michelini G., Kitsune V.,

Vainieri I., Hosang G.M., Brandeis D., Asherson P. Shared and disorder-specific

event-related brain oscillatory markers of attentional dysfunction in ADHD and

bipolar disorder. Brain topography, 2018;31:672-89.

37.

Cortese S., Moreira-Maia

C.R., Fleur D., Morcillo-Peñalver C., Rohde L.A., Faraone S.V. Association

between ADHD and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American

Journal of psychiatry, 2016;173(1):34-43.

38.

Romo L., Rémond J.J.,

Coeffec A., Kotbagi G., Plantey S., Boz F. Gambling and Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorders (ADHD) in a population of french students. Journal of

Gambling Studies, 2015;31:1261-72.

39.

Sobanski E., Banaschewski

T., Asherson P., Buitelaar J., Chen W., Franke B. Emotional lability in

children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD):

clinical correlates and familial prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,

2010; 51(8):915-23.

40.

Jepsen J.R.M., Fagerlund

B., Mortensen E.L. Do attention deficits influence IQ assessment in children

and adolescents with ADHD? Journal of Attention Disorders, 2009;12(6):551-62.

41.

Dekkers T.J., Popma A.,

Rentergem J.A.A., Bexkens A., Huizenga H.M. Risky decision making in

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-regression analysis. Clinical

psychology review, 2016;45:1-16.

42.

Bachmann C.J., Philipsen

A., Hoffmann F. ADHD in Germany: trends in diagnosis and pharmacotherapy: a

country-wide analysis of health insurance data on

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and

adults from 2009–2014. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 2017;114(9):141.

43.

Loflin M., Earleywine M.,

De Leo J., Hobkirk A. Subtypes of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD) and cannabis use. Substance use & misuse, 2014;49(4):427-34.

44.

Wilens T.E. Impact of ADHD

and its treatment on substance abuse in adults. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

2004;65:38-45.

45.

Notzon D.P., Pavlicova M.,

Glass A., Mariani J.J., Mahony A.L., Brooks D.J. ADHD is highly prevalent in

patients seeking treatment for cannabis use disorders. Journal of attention

disorders, 2020;24(11):1487-92.

46.

Romo L., Ladner J., Kotbagi

G., Morvan Y., Saleh D., Tavolacci M.P. Attention-deficit hyperactivity

disorder and addictions (substance and behavioral): Prevalence and

characteristics in a multicenter study in France. Journal of Behavioral

Addictions, 2018;7(3):743-51.

47.

Sobanski E., Brüggemann D.,

Alm B., Kern S., Deschner M., Schubert T. Psychiatric comorbidity and

functional impairment in a clinically referred sample of adults with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European archives of

psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 2007;257:371-7.

48.

Park S., Cho M.J., Chang

S.M., Jeon H.J., Cho S.J., Kim B.S. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidities

of adult ADHD symptoms in Korea: results of the Korean epidemiologic catchment

area study. Psychiatry Res, 2011;186(2-3):378-83.

![]() (1)

(1)