An examination of

the cytomorphological trends in tuberculous lymphadenitis at a tertiary care

hospital of southern Assam

Sukanya

Choudhury 1, Payel Hazari 1*, Nicky Choudhury 1,

Shah Alam Sheikh 1

1 Department of Pathology, Silchar Medical

College and Hospital, India

Corresponding

Authors: Payel Hazari

* Email: hazari.payel2@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Tuberculous lymphadenitis is a leading cause of

lymph node enlargement accounting for 195 per 1,00,000 population in India.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is rapid and economical compared to

other tests and thus plays a crucial role in diagnosing this condition. It

prevents unnecessary biopsy of lymph nodes and it can be used for collection of

material for cytomorphological and bacteriological examination. This study

aimed to assess the cytomorphological patterns of tuberculous lymphadenitis and

correlate them with Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining. Primary

aim is to assess the cytomorphological patterns of tubercular lymphadenitis and

to correlate with the bacteriological results using ZN staining.

Materials and methods: The FNAC results of 100 cases diagnosed with tuberculous lymphadenitis

over a period of one year were analyzed from the

cytopathology section of Silchar Medical College and

Hospital. The findings were classified into three patterns: pattern A -

epithelioid granuloma in absence of caseous necrosis, pattern B - epithelioid

granuloma with caseous necrosis, and pattern C - caseous necrosis in absence of

epithelioid granuloma. The cytomorphological patterns were then correlated with

acid-fast bacilli (AFB) positivity.

Results: In individuals between the ages of 21 and 30,

tuberculous lymphadenitis was predominantly observed. The cervical lymph node

(92%) was the most frequently affected area. Among the different patterns of

the condition, Pattern B, which is characterized by the presence of epithelioid

granuloma along with caseous necrosis, was found to be the most common (53%).

In contrast, Pattern C, which is marked by caseous necrosis without the

presence of epithelioid granuloma, exhibited the highest positivity for acid-fast

bacilli (80%). The difference in AFB positivity among the patterns was

statistically significant (P-value= 0.0003).

Conclusion: FNAC is an effective and economical

diagnostic tool for tuberculous lymphadenitis, particularly in resource-limited

settings. The study found that Pattern B (epithelioid granuloma with caseous

necrosis) was the most common, while Pattern C (caseous necrosis without

epithelioid granuloma) exhibited the highest AFB positivity. FNAC, combined

with ZN staining, enhances the accuracy of tuberculosis diagnosis, minimizing

the need for invasive biopsies. Given the high prevalence of tuberculosis, FNAC

should be the first-line investigation for patients presenting with superficial

lymphadenopathy, ensuring timely diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Cytomorphological patterns, Tuberculous lymphadenitis, Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining, Acid-fast bacilli

Introduction

Tuberculosis is very common in India accounting for

195 per 1,00,000 population (1). Lymphadenitis is the most common clinical

presentation of extrapulomonary tuberculosis with

tubercular lymphadenitis accounting for 43% cases in developing countries like

India. Diagnosis of tuberculosis can be done by various diagnostic methods as

fine needle aspiration cytology, biopsy, Acid fast bacilli culture and polymerase

chain reaction .(1) FNAC is a widely used cytological

technique for diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis offering a sensitivity and

specificity of 88-96% and is most cost effective and rapid compared to other

tests like AFB culture and PCR (2). FNAC can detect tubercular lymphadenitis

even in cases where the bacterial load is low or when the disease is in its

early stages.

The sensitivity increases significantly when FNAC is

combined with Ziehl-Neelsen staining for acid-fast bacilli .The presence of epithelioid cell granulomas,

caseous necrosis, and Langhans giant cells on cytology strongly points to a

tubercular etiology, leading to accurate diagnosis

and exclusion of other causes of lymphadenopathy (e.g., lymphoma, metastatic

carcinoma).

It also minimises unnecessary lymph node biopsies and

providing material for cytopathological and bacteriological analysis (3).

Its ability to provide rapid cytological and

bacteriological insights makes it invaluable in early diagnosis and management

of TB, especially in high-burden and resource-limited settings. Combining FNAC

with other tests like ZN staining further enhances its diagnostic yield and

clinical utility.

To diagnose tuberculosis cytologically, the

identification of epithelioid cell granuloma with or without necrosis is

essential (4-7). A confirmed diagnosis is achieved by identifying the presence

of acid-fast bacilli by doing ZN staining.

This study undertakes a comprehensive examination of

the cytomorphological patterns of tubercular lymphadenitis, with a specific

focus on correlating FNAC findings with bacteriological confirmation via ZN

staining. This study aims to thoroughly analyze the

cytomorphological patterns

observed in tubercular lymphadenitis using FNAC. The goal is to

identify and describe the specific cellular changes and features such as

granulomas, caseous necrosis, and giant cells seen in FNAC smears from patients

with tubercular lymphadenitis.

Additionally, the study seeks to establish a

correlation between the FNAC findings and bacteriological confirmation of

tuberculosis through ZN staining. A positive correlation would mean that the

cytological features identified in FNAC are consistent with the presence of AFB

as confirmed by ZN staining, thereby strengthening the diagnostic value of FNAC

for tubercular lymphadenitis.

Materials

and methods

The present study was undertaken to assess the

cytomorphological patterns of tubercular lymphadenitis and to correlate with

the bacteriological results using Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN)

staining.

This study was conducted in the Department of

Pathology, Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Silchar, Assam, India. The Institutional Ethics Committee

approved the study (No.SMCH/ETHICS/M2/2024/46)

on 30/08 /2024. The study is compliant with the Helsinki Declaration’s ethical

guidelines.

Study period

1 year period: From August 2023 to July 2024

Source of data and sample size

100 patients were diagnosed with tuberculous

lymphadenitis based on FNAC of peripheral lymphadenopathy and the data were

collected from the registers of the cytopathology section of the Pathology

department of Silchar Medical College and Hospital.

The FNAC slides stained with MGG and ZN stains were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria

Clinically suspected

cases of tubercular lymphadenitis and those not on anti

tuberculosis treatment (ATT)

Exclusion

criteria

·

On

anti-tubercular treatment.

·

FNAC samples yielding inadequate or

non-diagnostic material.

Parameters

studied

·

Detailed clinical history and other investigations of the patients were

recorded after taking patient consent.

·

Hospital records of the patients.

·

Microscopic examination of the FNAC slides.

This study, conducted from 2023 to 2024 at Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Assam, involved 100

patients diagnosed with tuberculous lymphadenitis through FNAC of peripheral

lymphadenopathy. Data were collected from cytopathology registers, and FNAC

slides stained with MGG and ZN stains were reviewed. Characteristic

cytomorphological features, including epithelioid granuloma with or without

caseous necrosis and ZN staining, confirmed the diagnosis.

The following techniques were performed in the

preparation of FNAC (Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology) slides:

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC)

procedure

1. Preparation for the procedure

1.1 Materials required

·

Syringe: Disposable plastic syringe (10-20 ml

capacity)

·

Needle: 20-22 gauge

needle (length varies based on tumor site)

·

Antiseptic solution: For cleaning the puncture site

·

Glass slides: For smear preparation

·

Staining reagents: May-Grunwald Giemsa (MGG) and Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stains

1.2 Patient Preparation

·

The patient is positioned comfortably and reassured to reduce

anxiety.

·

No local anesthesia is required as FNAC is a

minimally invasive procedure.

·

The target mass is localized by palpation, and a suitable puncture site

is chosen.

2. Aspiration procedure

2.1 Needle insertion and aspiration

1. The skin around the target site is

thoroughly cleaned with an antiseptic solution.

2. The lesion is held firmly in place with one

hand while the needle is inserted at the predetermined site.

3. Once the needle enters the lesion, the

syringe plunger is retracted to create negative pressure for aspiration.

4. The needle is moved within the mass (3-4

oscillations in different directions) to obtain an adequate sample.

2.2 Withdrawal and sample handling

5. Before withdrawing the needle, the plunger

is released to equalize pressure, preventing blood contamination.

6. The needle is then removed, and detached from

the syringe, and air is drawn into the syringe to facilitate sample expulsion.

7. The needle is reattached, and the aspirated

material is expelled onto a clean glass slide.

3. Preparation of Smears

3.1 Spreading the aspirate

·

The aspirate is examined macroscopically.

·

Semi-solid aspirates are spread using a thick Burker-type cover slip.

·

Tissue fragments are gently crushed for uniform distribution.

4. Staining Procedure

4.1 May-Grunwald Giemsa (MGG) Staining

1. The air-dried smear is fixed in

methanol.

2. May-Grunwald stain is applied for 5-7

minutes, followed by Giemsa stain for 10-15 minutes.

3. The slide is rinsed with buffered water

until the excess stain is removed.

4. The slide is then air-dried and ready for

microscopic examination.

4.2 Ziehl-Neelsen

(ZN) Staining for Acid-Fast Bacilli (AFB)

4.2.1 Primary staining

1. The air-dried and heat-fixed smear is

flooded with carbol fuchsin stain.

2. The slide is gently heated until steam

appears (without boiling) to ensure dye penetration.

3. It is left to stand for 5-10 minutes to

allow effective staining.

4.2.2 Decolorization

1. The slide is washed with water.

2. It is decolorized using acid-alcohol (20%

sulfuric acid or 3% hydrochloric acid in ethanol) until the red stain fades.

3. The slide is rinsed again with water.

4.2.3 Counterstaining

1. Methylene blue or malachite green is

applied for 1-2 minutes to provide a contrasting background.

2. The slide is washed, air-dried, and ready

for microscopic evaluation.

5. Slide Interpretation and reporting

5.1 Cytomorphological classification

The FNAC results are classified into three patterns:

·

Pattern A: Epithelioid granuloma without necrosis

·

Pattern B: Epithelioid granuloma with necrosis

·

Pattern C: Necrosis without epithelioid granuloma,

with neutrophilic infiltration

5.2 Statistical Analysis

·

Software Used: SPSS (Version 21)

·

Test performed: Chi-square test to correlate

cytomorphological patterns with AFB positivity.

·

Significance level: A p-value < 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Out

of the 100 patients studied, 42 (42%) were male and 58 (58%) were female,

indicating a slight female predominance, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.4. The

ages of the patients ranged from 1 to 71 years, with an average age of 29.28

years. The disease was most prevalent in the age group of 21 to 30 years,

followed by the 11 to 20 years age group (Table 1). Cervical lymph nodes were

the most commonly affected, involved in 92% of cases, while inguinal lymph

nodes were affected in 8% of cases.

Table

1. The patient

information.

|

|

Total (%)

|

|

Gender

|

Male

|

42

|

|

Female

|

58

|

|

Age group

|

01-10 years

|

8

|

|

11-20 years

|

16

|

|

21-30 years

|

38

|

|

31-40 years

|

13

|

|

41-50 years

|

12

|

|

51-60 years

|

5

|

|

61-70 years

|

6

|

|

71-80 years

|

2

|

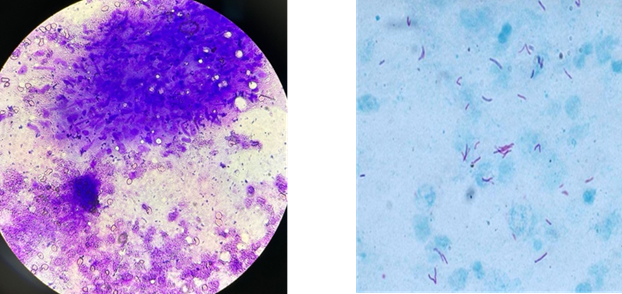

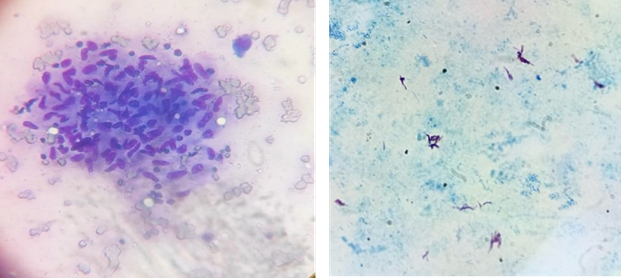

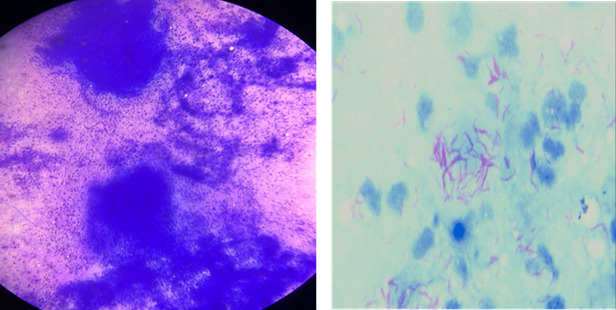

Three distinct cytopathological patterns were

identified: Pattern A, which consisted of epithelioid granuloma in the absence

of caseous necrosis; Pattern B, which included epithelioid granuloma with

necrosis; and Pattern C, characterized by caseous necrosis without epithelioid

granuloma (refer to Table 2 and Figures 1 A, B, and C).

Among these patterns, Pattern B was the most

prevalent, observed in 53 cases out of 100, representing a partially effective

immune response where granulomas are present, but necrosis indicates tissue

destruction and active bacterial replication.

Pattern A was

the second most prevalent, observed in 42 cases, thus representing a contained

immune response where macrophages are effectively forming granulomas to control

bacterial proliferation.

The least prevalent was pattern C, observed in 5

cases, reflecting a defective immune response where the absence of granuloma

formation allows bacterial proliferation and leads to extensive tissue damage.

A Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast

bacilli, indicative of tuberculosis, revealed AFB positivity in 47 cases. The

distribution of AFB positivity across the three cytopathological patterns was

as follows: Pattern B had 33 positive cases out of 53 (62.3%), Pattern A had 10

positive cases out of 42 (23.8%), and Pattern C had 4 positive cases out of 5

(80%). Thus the highest percentage of AFB positivity

was seen in Pattern C, where there was no epitheloid

granuloma formation indicating a

ineffective immune response and thus increased bacillary load.

The differences in AFB positivity among the patterns

were statistically significant, with a P value of 0.0003 and a Chi-square value

of 16.211.

The statistically significant differences confirm that

Pattern C is strongly associated with high bacillary load and poor immune

control. The lower AFB positivity in Pattern A reflects an effective immune

response, while the higher AFB positivity in Pattern B and Pattern C reflects

progressive or poorly contained infection.

Pattern B’s predominance suggests that most cases of

tubercular lymphadenitis involve an active immune response with ongoing tissue

destruction.

The high AFB

positivity in Pattern C highlights the need for aggressive antitubercular

therapy in cases where granuloma formation is absent, as these cases are likely

to have higher bacterial loads.

The low AFB

positivity in Pattern A underscores the protective role of granuloma formation

in containing TB infection.

This analysis supports the use of FNAC not only for

diagnosis but also for predicting disease severity and guiding treatment

strategies.

Table

2. Cytomorphological

patterns of tubercular lymphadenitis.

|

Cytopathological pattern

|

Total no. of cases

|

AFB positive cases

|

AFB negative cases

|

AFB positivity (%)

|

|

Pattern B

|

53

|

33

|

20

|

62.3%

|

|

Pattern A

|

42

|

10

|

32

|

23.8%

|

|

Pattern C

|

5

|

4

|

1

|

80%

|

|

Total

|

100

|

47

|

53

|

|

|

|

|

P value=

0.0003

|

|

|

Discussion

FNAC is the primary method

for reliably diagnosing tubercular lymphadenitis in patients who present with

superficial lymphadenopathy, as it is simple, safe, and cost-effective (8). In

our study, the mean age of presentation and the age group exhibiting the

highest incidence of tubercular lymphadenitis is consistent with studies

conducted by Bhatta S et al. and Hemalatha A et al (9,10) , where the most

frequent age group effected was 21-30 years .There was a slight female

predominance(Male: Female-1.4:1) , which aligns with results from Purohit MR, et al (4) (Male: Female- 1.5:1) and

Polesky et al. (female to male ratio of 1.9:1) (16).

The most commonly involved

lymph node in our study was the cervical lymph node(92%)

which corresponds with the study by Bezabith M et

al., which reported a 74.2% involvement of lymph nodes, and the research by

Paliwal N et al., which indicated a 90% involvement rate (8,13).

The most commonly observed

pattern was Pattern B(53%), epithelioid granuloma with

caseous necrosis, which was also the most prevalent in studies by Bhatta S et

al ( 9) (53.17%) and Khanna A et al (14) (50.5%). The

least common pattern in our study was caseous necrosis without epithelioid

granuloma (5%), observed.

The overall positivity for

Acid-Fast Bacilli in our study was 47%. An inverse relationship was found

between AFB positivity and the presence of granuloma: the highest AFB

positivity was seen in smears containing only necrosis and neutrophilic

infiltrates, while the lowest was found in smears with only epithelioid

granulomas. The patient’s cell-mediated immunity triggers a granulomatous

response against tubercle bacilli, resulting in lower AFB positivity in smears

showing epithelioid granuloma without necrosis. In contrast, smears containing

only necrotic material demonstrated higher AFB positivity due to a compromised

immune response and the absence of a granulomatous reaction. Paliwal N et al.

and Bezabith M et al. reported overall AFB positivity

rates of 71% and 59.5%, respectively (9,14,15). The relatively low AFB

positivity in our study may be attributed to the predominance of epithelioid

granuloma with or without necrosis. Repeating Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology

may improve AFB positivity rates. The association between AFB positivity and

the three cytomorphological patterns in our study was statistically significant

(p = 0.0003).

The clinical outcomes can

vary based on the patterns and their findings as discussed below:

1. Granuloma with Caseous

Necrosis: This pattern indicates an active immune response to the infection. It

generally has a favorable prognosis, as it responds

well to anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT). The presence of granulomas and caseous

necrosis suggests that the body is successfully containing the infection,

leading to a complete resolution with treatment. Relapse rates tend to be low

if the treatment is completed properly.

2. Granuloma without Caseous

Necrosis: This may indicate an early or less severe form of the infection,

where the immune system is managing to contain the bacteria before extensive

tissue damage occurs. The prognosis is still good because these cases usually

respond well to ATT, and there is often less tissue damage to repair. However,

close follow-up is essential to ensure that the infection does not progress to

the caseous necrosis stage.

3. Necrosis without

Granuloma: This pattern may suggest a compromised or ineffective immune

response, as the typical granuloma, which encloses the infection, is absent.

This scenario may arise in cases with a high bacillary load or in

immunocompromised patients. The prognosis for these cases is generally poorer

compared to the other patterns, as there is a higher risk of infection spread

and complications. Treatment response can be slower, and these cases require

more intensive monitoring and longer follow-up to ensure complete resolution of

the infection.

The following limitations must be acknowledged in this

study:

- Restricted

Study Population – The study only

included cases from a single institution (Silchar

Medical College and Hospital), limiting its generalizability to a broader

population. Cases from private hospitals and rural healthcare centers were not considered.

- Exclusion

of Certain Diagnostic Methods –

Patients who underwent additional investigations such as CBNAAT could not

be included due to a lack of traceability, which may have impacted the

study’s ability to compare different diagnostic techniques.

These limitations suggest that while the study

provides valuable insights, a more comprehensive, multi-center

approach could enhance its applicability and accuracy.

Conclusion

This study highlights the diagnostic utility of Fine

Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) in identifying cytomorphological patterns of

tuberculous lymphadenitis and correlating them with bacteriological

confirmation via Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining. The key

findings include:

1. Prevalence and Demographics: Tuberculous lymphadenitis predominantly affects

individuals between 21 and 30 years of age, with a slight female predominance.

The cervical lymph nodes are the most commonly involved (92%).

2. Cytomorphological Patterns: The most prevalent pattern was Pattern B

(epithelioid granuloma with caseous necrosis, 53%), indicating an active immune

response with ongoing tissue destruction. Pattern A (epithelioid

granuloma without necrosis, 42%) reflects a well-contained immune response,

whereas Pattern C (caseous necrosis without granuloma, 5%) suggests a

defective immune response and higher bacillary load.

3. AFB Positivity: The highest AFB positivity (80%) was observed in Pattern C,

indicating poor immune containment, followed by Pattern B (62.3%) and Pattern

A (23.8%). The association between AFB positivity and cytomorphological

patterns was statistically significant (p = 0.0003).

4. Clinical Implications:

o

Pattern B cases respond well to anti-tuberculosis

therapy (ATT) with a favorable prognosis.

o

Pattern A cases require close monitoring to prevent

progression to necrosis.

o

Pattern C cases, with high bacterial loads,

necessitate aggressive ATT and close follow-up due to the risk of

complications.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

·

FNAC should be the first-line diagnostic approach for superficial

lymphadenopathy, particularly in resource-limited settings, as it is minimally

invasive, cost-effective, and provides rapid results.

·

ZN staining enhances diagnostic accuracy, helping distinguish between

different immune responses to tuberculosis.

·

Treatment strategies should be tailored based on cytomorphological

patterns to ensure better disease management and patient outcomes.

·

Further research is needed to validate these findings across multiple

healthcare centers and integrate molecular diagnostic

tools like CBNAAT for enhanced sensitivity.

This study reinforces FNAC’s role in diagnosing

tuberculous lymphadenitis and guiding treatment, ultimately contributing to

better tuberculosis control strategies.

Acknowledgments

The

author would like to extend thanks to the technicians of cytopathology section

for their help. This research received no specific grant from any funding

agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Author

contribution

All the authors of this research paper have

directly participated in the planning, execution, or analysis of the study. SCh

and PH conceived the idea, designed the study, SCh and NCh collected the data, SCh and PH performed

the statistical analysis and wrote the paper. ShASh

guided the research project and reviewed the slides and the literature. All

the authors of this paper have read and approved the final version submitted.

Conflict

of interest

The

authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

There

is no funding agency involved in this research.

References

1. Gupta

A, Kunder S, Hazra D, Shenoy VP, Chawla K. Tubercular lymphadenitis in the 21st

century: A 5-Year single-center retrospective study from South India. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2021 Apr-Jun;10(2):162-165.

2.

Lawn SD, Churchyard G. Epidemiology of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Current

Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2009 Jul 1;4(4):325-33.

3.

Khajuria R, Goswami KC, Singh K, Dubey VK. Pattern of lymphadenopathy on fine

needle aspiration cytology in Jammu. JK Sci. 2006 Jul;8(3):157-9.

4.

Purohit MR, Mustafa T, Mørkve O, Sviland L. Gender

differences in the clinical diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis—a

hospital-based study from Central India. International Journal of Infectious

Diseases. 2009 Sep 1;13(5):600-5.

5.

Giri S, Singh K. Fine needle aspiration cytology for the diagnosis of

tuberculous lymphadenitis. International Journal of Current Research and

Review. 2012 Dec 15;4(24):124.

6.

Butt T, Ahmad RN, Kazmi SY, Afzal RK, Mahmood A. An update on the diagnosis of

tuberculosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003 Dec;13(12):728-34. PMID:

15569566.

7.

Laishram RS, Devi RK, Konjengbam R, Devi RK, Sharma

LD. Aspiration cytology for the diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenopathies: A

five-year study. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2010

Jan;11(1):31-5.

8. Bezabih M, Mariam DW, Selassie SG. Fine needle aspiration

cytology of suspected tuberculous lymphadenitis. Cytopathology. 2002

Oct;13(5):284-90.

9.

Bhatta S, Singh S, Chalise SR. Cytopathological patterns of tuberculous

lymphadenitis: An analysis of 126 cases in a tertiary care hospital. Int. J.

Res. Med. Sci. 2018 Jun;6(6):1898-901.

10.

Hemalatha A, Shruti PS, Kumar MU, Bhaskaran A. Cytomorphological patterns of

tubercular lymphadenitis revisited. Annals of medical and health sciences

research. 2014;4(3):393-6.

11.

Paul PC, Goswami BK, Chakrabarti S, Giri A, Pramanik R. Fine needle aspiration

cytology of lymph nodes-An institutional study of 1448 cases over a five year period. Journal of Cytology. 2004 Oct

1;21(4):187-90.

12.

Gopinathan VP. Tuberculosis in the Indian scene. From a clinician's angle. The

Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 1989 Aug 1;37(8):525-8.

13.

Nidhi P, Sapna T, Shalini M, Kumud G. FNAC in tuberculous lymphadenitis:

Experience from a tertiary level referral centre.

Indian J Tuberc. 2011 Jul 1;58(3):102-7.

14.

Khanna A, Khanna M, Manjari M. Cytomorphological patterns in the diagnosis of

tuberculous lymphadenitis. International Journal of Medical and Dental

Sciences. 2013;2(2):182-8.

15.

Prasoon D. Acid-fast bacilli in fine needle aspiration smears from tuberculous

lymph nodes. Acta cytologica. 2000;44(3):297-300.

16.

Polesky, Andrea MD, PhD; Grove, William MD; Bhatia, Gulshan MRCP(UK).

Peripheral Tuberculous Lymphadenitis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and

Outcome. Medicine 84(6):p 350-362, November 2005.