Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in

adults exposed to oral antidiabetic drugs: a systematic review

Shadman Newaz 1*, Monami

Ahmed 2, Snigdho Hritom

Sil 1, Mst Samanta Hoque 3, Mehbub Hossain 1, Tonima Tabassum Dola 1,

Afia Anjum 1, Sohana Nasrin 4, Ayesha Noor 5

1 Tangail Medical College, Tangail, Bangladesh

2 Department of Anatomy, Medical College for Women and Hospital,

Dhaka, Bangladesh

3 Rajshahi Medical

College, Rajshahi, Bangladesh

4 Sir Salimullah Medical College, Dhaka,

Bangladesh

5 Department of Pharmacy, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

* Corresponding

Author: Shadman Newaz

* Email: shadmannewaz11@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: An increasing amount

of clinical research is being conducted on the association between antidiabetic

medications and the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. By offering a

thorough synthesis of the available data and pinpointing topics for further

investigation, this systematic review seeks to assess any possible correlations

between the results.

Materials and methods: According to a registered protocol on the Open Science Framework,

we carried out a systematic review of research published between January 2015

and March 2025. We reviewed several databases to identify English-language

research employing a range of study designs, including observational studies,

cohort studies, and clinical trials. After a thorough screening procedure, 18

studies were chosen from 1089 records. Following the parameters of this study,

the main objective was to summarize the evidence without doing a formal quality

assessment.

Results: Our analysis found possible connections between liver cancer

outcomes and several antidiabetic groups, including insulin, metformin,

thiazolidinediones, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, GLP-1

receptor agonists, and DPP-4 inhibitors. Metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists,

and SGLT2 inhibitors were consistently associated with reduced risk of

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and improved survival outcomes. In contrast,

insulin use in cirrhotic patients was linked to increased all-cause mortality

and higher liver-related complications. Thiazolidinediones showed a

time-dependent protective effect, with longer use correlating with lower HCC

risk. The results suggest that some antidiabetic drugs may affect overall

survival, recurrence rates, and mortality specific to liver cancer. We

discovered that rather than being an initiating factor, the majority of

antidiabetic medications have decreased the risk of liver cancer.

Conclusion: This systematic review contributes to a better understanding of the

complex relationship between antidiabetic medications and liver cancer

outcomes. Important conclusions imply that medical professionals ought to think

about the possible effects of particular antidiabetic medications in liver

cancer patients. More extensive randomised controlled

trials with longer follow-up are advised to elucidate these correlations and

guide treatment recommendations.

Keywords: Antidiabetic drugs, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Liver Cancer, Medication

Associations, Diabetes

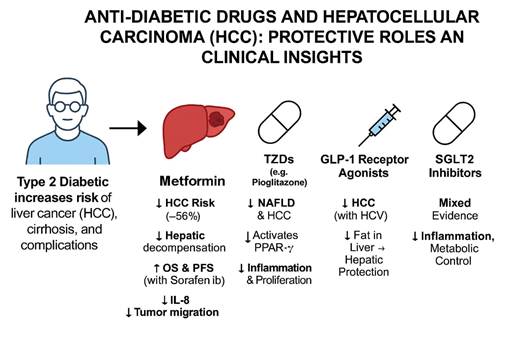

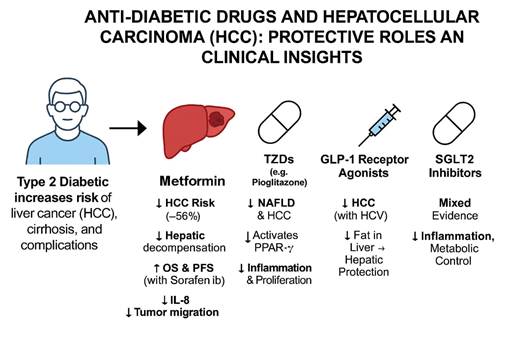

Graphical abstract

This graphical abstract illustrates the

protective roles of various anti-diabetic medications against hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) in patients with type 2 diabetes. The figure begins by

highlighting the increased risk of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and complications

in diabetic individuals. Among the medications, Metformin shows the most

consistent protective effects, including a 56% reduction in HCC risk, improved

survival outcomes, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

like pioglitazone reduce NAFLD and HCC through PPAR-γ activation. GLP-1

receptor agonists offer hepatic protection and are particularly beneficial in

HCV-associated liver disease. DPP-4 inhibitors (not shown) also lower HCC risk

in chronic HCV patients. SGLT2 inhibitors exhibit mixed evidence, with

population-dependent benefits through inflammation and metabolic control. This

summary highlights the evolving role of diabetes medications in liver cancer

prevention and management.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a globally prevalent metabolic

disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from insulin

resistance, impaired insulin secretion, or a combination of both. As of 2021,

more than 537 million people worldwide were estimated to have diabetes, a

number projected to rise significantly over the coming decades (1). The

management of T2DM primarily involves lifestyle modification and

pharmacotherapy with a range of antidiabetic agents that act through diverse

mechanisms—enhancing insulin secretion, improving insulin sensitivity, reducing

hepatic glucose production, or delaying carbohydrate absorption (2).

Liver cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) being the predominant histological subtype,

accounting for approximately 75–85% of primary liver cancers globally (3). HCC

typically develops in the context of chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis

B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcoholic liver disease,

and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), all of which contribute to a

pro-oncogenic hepatic microenvironment characterized by inflammation, fibrosis,

and cellular turnover (4).

Importantly, T2DM has emerged as an independent risk factor for the

development of HCC, with epidemiological studies showing a 2- to 3-fold

increased risk among diabetic individuals compared to non-diabetic

counterparts, even after adjusting for confounding factors such as obesity and

viral hepatitis (5). The biological plausibility of this association is

supported by multiple mechanisms, including chronic hyperinsulinemia, increased

insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) activity, oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, and chronic low-grade inflammation—all of

which may contribute to hepatic carcinogenesis (6,7).

Antidiabetic medications, while crucial for glycemic control and

prevention of micro- and macrovascular complications, may also influence the

risk of HCC either positively or negatively. For example, metformin, a

biguanide, has demonstrated potential anti-tumorigenic properties through

activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), suppression of hepatic

gluconeogenesis, and reduction in insulin levels—mechanisms that may contribute

to decreased HCC risk (8). Conversely, other classes such as insulin, sulfonylureas,

and thiazolidinediones have shown variable or even increased

associations with liver cancer risk, possibly due to their proliferative

effects or impacts on hepatic steatosis and weight gain (9,10).

Adding to the complexity, comorbid conditions frequently seen in

T2DM patients—such as NAFLD, obesity, and chronic viral hepatitis—may interact

with specific medications to modulate the risk of liver carcinogenesis. The

presence of such conditions may alter hepatic drug metabolism, increase

susceptibility to hepatotoxicity, or modify the underlying pathophysiology

leading to cancer development (11,12).

Despite the growing body of literature on the association between

T2DM and liver cancer, previous reviews have often been limited in scope,

focusing either on the general relationship between diabetes and cancer risk or

on isolated drug classes without accounting for confounding comorbidities and

evolving treatment paradigms. Furthermore, with the introduction of newer

classes of antidiabetic drugs—such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2

inhibitors—there is an urgent need to evaluate their long-term hepatic

safety profiles and potential protective effects (13,14).

Objective of the Review

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of

the available evidence on the relationship between antidiabetic medications and

liver cancer outcomes, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma. Specifically, it

seeks to:

·

Evaluate the impact of individual

antidiabetic drug classes (e.g., metformin, insulin, sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors,

GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT-2 inhibitors) on the incidence, progression,

recurrence, and mortality of liver cancer.

·

Explore the role of underlying

hepatic conditions (e.g., cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, NAFLD) and patient-level

risk factors (e.g., age, obesity, duration of diabetes) in modifying these

associations.

·

Identify potential protective or

harmful effects based on drug type, duration of exposure, and population

subgroups.

·

Provide evidence-based insights to

guide clinical decision-making in the pharmacological management of T2DM in

patients at risk for liver cancer.

By bridging the current knowledge gap and synthesizing diverse data

sources, this review aims to support more informed, personalized, and safer

antidiabetic therapy decisions in patients at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Study Design and Protocol Registration

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

guidelines. The review protocol was prospectively registered on the Open

Science Framework (OSF) to ensure transparency and methodological rigor. The

primary objective was to synthesize existing literature on the relationship

between antidiabetic medications and liver cancer outcomes. Due to anticipated

heterogeneity in study populations, medication types, and outcome definitions,

a narrative synthesis was chosen over a meta-analysis to summarize the

findings.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

·

Peer-reviewed articles published

between January 2015 and March 2025.

·

Study designs: Randomized controlled

trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies, and observational studies.

·

Studies reporting on the impact of

antidiabetic medications (e.g., metformin, insulin, sulfonylureas, SGLT-2

inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors, thiazolidinediones) on

liver cancer outcomes.

·

Population: Adults with diabetes

mellitus (type 1 or type 2), with or without pre-existing liver disease.

·

Outcomes: Incidence, progression,

recurrence, survival, or mortality of liver cancer.

·

Published in English.

Exclusion Criteria:

·

Studies published prior to January

2015 due to outdated diagnostic standards and drug classifications.

·

Non-English articles.

·

Conference abstracts, editorials,

commentaries, and study protocols.

·

Studies addressing other cancer

types without specific liver cancer data in relation to antidiabetic use.

·

Animal or in vitro studies.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted across the

following databases:

·

PubMed

·

ScienceDirect

·

Cochrane CENTRAL

·

Mendeley

The search strategy combined MeSH terms

and free-text keywords using Boolean operators. Key search terms included:

·

Antidiabetic agents:

"metformin" OR "insulin" OR "sulfonylureas" OR

"DPP-4 inhibitors" OR "GLP-1 receptor agonists" OR

"SGLT-2 inhibitors" OR "thiazolidinediones" OR

"glinides" OR "antidiabetic drugs"

·

Liver cancer: "liver

cancer" OR "hepatocellular carcinoma" OR

"cholangiocarcinoma" OR "liver carcinoma" OR "hepatic

neoplasms"

·

Combined terms:

o

"diabetes

treatment" AND "liver cancer risk"

o

"antidiabetic

side effects" AND "liver cancer survival"

o

"risk

of liver cancer" AND "antidiabetic drugs"

Filters applied included:

·

Publication date from January 2015

to March 2025

·

English language

·

Human subjects only

The initial search was performed on January 26, 2025, with an

update on March 26, 2025. Additionally, the reference lists of relevant reviews

and included studies were manually screened to identify additional eligible

publications.

Study Selection Process

The selection process was conducted using Rayyan, a web-based tool

for systematic review screening. Two reviewers (TD and MSH) independently

screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations. Full texts of

potentially eligible studies were then assessed for inclusion. Any

disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (SS). A PRISMA flow diagram was

generated to illustrate the screening and selection process.

Data Extraction

A standardized data extraction form was developed in Microsoft

Excel. Extracted variables included:

·

Author(s) and year of publication

·

Country and setting

·

Study design

·

Sample size and characteristics

·

Type(s) of antidiabetic

medication(s) assessed

·

Liver cancer outcomes (incidence,

progression, survival, etc.)

·

Key findings and effect estimates

·

Confounding factors and statistical

methods

Primary extraction was performed by SN, with independent

verification of 50% of the entries by MA and MH to ensure accuracy and

consistency.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

Although this review did not exclude studies based on quality, a descriptive

appraisal was undertaken. The following tools were used:

·

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for

cohort and case-control studies

·

Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) for RCTs

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of included

studies. Risk of bias domains evaluated included:

·

Selection bias

·

Performance bias

·

Detection bias

·

Attrition bias

·

Reporting bias

·

Confounding and exposure

misclassification

High-risk studies were not excluded but were analyzed separately

when applicable. A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the

robustness of the review findings when excluding studies rated as high risk of

bias.

Data Synthesis

Given the diversity in study designs, populations, drug

classifications, and outcome measures, a narrative synthesis approach was

adopted. Findings were grouped by antidiabetic drug class and type of liver

cancer outcome (e.g., incidence, survival, recurrence). Patterns of

associations, inconsistencies, and gaps in evidence were summarized

thematically. Quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was not feasible due to

substantial heterogeneity across included studies.

Ethical Considerations

As this study was a review of previously published data, no ethical

approval or informed consent was required.

Results

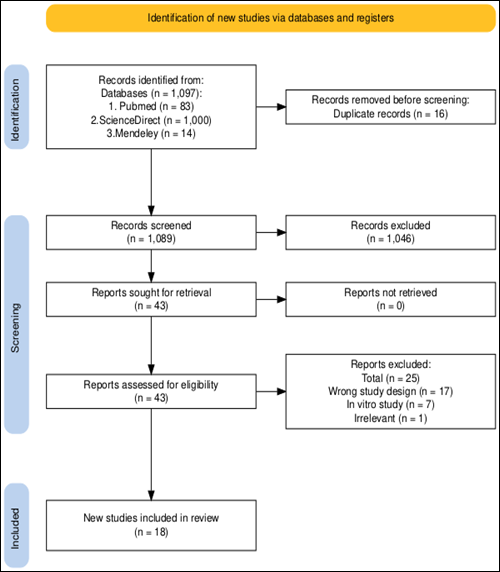

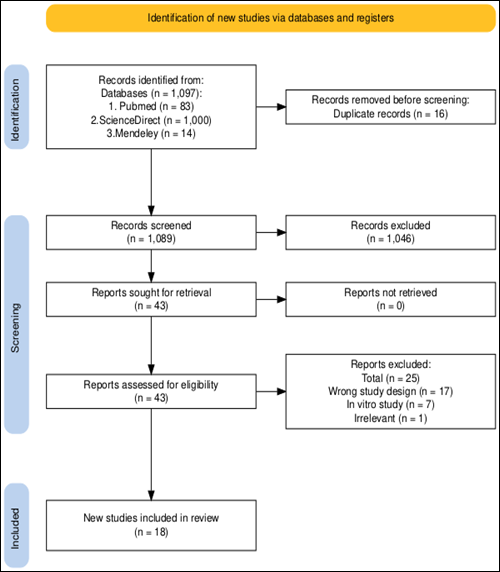

The review process details are depicted in

the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). A total of 1,097 records were identified through database searches, including

Science Direct (n=1,000), PubMed (n=83), and Mendeley (n=14). After removing 16 duplicate records, 1089 records remained for title and

abstract screening. Following this initial screening, 1,046 records were excluded based on irrelevance to the study

objectives. Subsequently, 43 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility.

Among these, 25 studies were

excluded due to reasons such as wrong study design (n=17), in vitro study

(n=7), and irrelevant outcome (n=1). Ultimately, 18 studies met the inclusion

criteria and were included in the systematic review for further in-depth

analysis on the core relationship between antidiabetic drugs and the risk of

developing liver cancer.

Figure 1. Prisma flow

diagram illustrating the study selection process.

This flowchart

illustrates the PRISMA process used for identifying, screening, and including

studies in a systematic review. It shows the number of records retrieved from

databases, the removal of duplicates, the number of records screened and

excluded, and the final count of studies included in the review (n = 18). The

diagram also details reasons for exclusion at each stage.

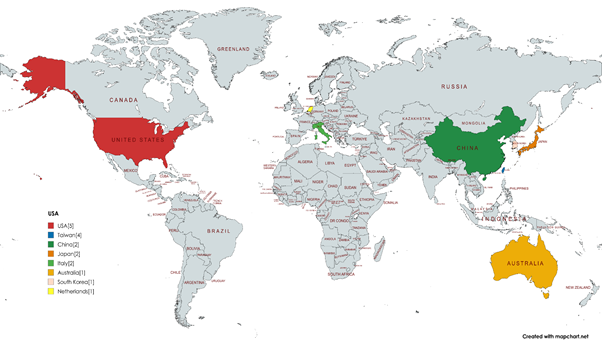

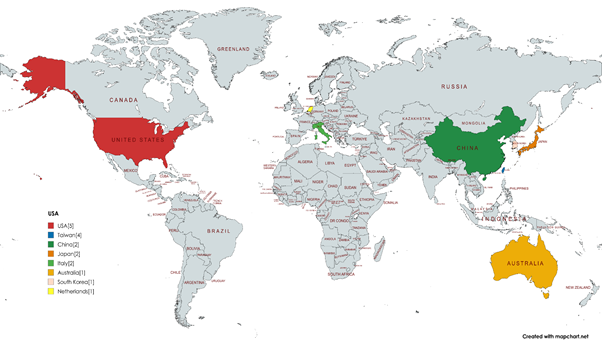

Participants and study characteristics

This systematic review included 18 studies,

encompassing a total of 3,572,638 participants across multiple geographic

regions (Table 1), including the USA, Taiwan, South Korea, China, Japan, Italy,

the Netherlands, and Australia. Among them, the USA contributed the highest

number of studies with 5, followed by Taiwan with 4, and China, Japan, and

Italy with 2 each. Several other countries, including South Korea, the

Netherlands, and Australia, each contributed 1 study.

This distribution highlights a significant

concentration of studies in the USA and East Asian countries, reflecting a

diverse geographic spread of research (Figure 2).

However, it is important to consider that

regional differences in diabetes prevalence, genetic predispositions,

healthcare infrastructure, and treatment protocols may have influenced the

outcomes observed. For instance, the pharmacogenomic response to antidiabetic

drugs and baseline liver cancer risk may vary between populations, potentially

limiting the generalizability of certain findings. Acknowledging these regional

disparities is essential when interpreting the data and applying conclusions

globally.

Table 1. Country distribution of

included studies.

|

Country

|

Count

|

|

USA

|

5

|

|

South Korea

|

1

|

|

Taiwan

|

4

|

|

China

|

2

|

|

Japan

|

2

|

|

Italy

|

2

|

|

Netherlands

|

1

|

|

Australia

|

1

|

Figure 2. Country

distribution of studies. The image indicates the number of representations

by country, with each color corresponding to a

different country. The USA has the highest count (5), followed by Taiwan (4),

and several countries with 1–2 representations each, including China, Japan,

Italy, Australia, South Korea, and the Netherlands.

The majority of studies were retrospective

cohort studies (n=15), followed by observational (cross-sectional study) (n=2)

and multicenter retrospective (n=2). Additionally,

Comparative cohort, population-based case-control study, and population-based

cohort, as well as clinical and preclinical experimental studies, were

observed. Overall, the data reflect a dominance of retrospective cohort designs

with a mix of other observational and experimental methodologies.

Table 2. Methodological Designs of Included Studies.

|

Study Method

|

Count

|

|

Retrospective Cohort Studies

|

14

|

|

Population-based case-control study

|

1

|

|

Cross-sectional Studies

|

2

|

|

Population-based Clinical Transitional

study

|

1

|

Most studies utilized retrospective cohort

designs, particularly in the USA and Taiwan, while European and East Asian

studies incorporated cross-sectional, case-control, and clinical transitional

methodologies. The study populations varied significantly in size, ranging from

7 participants in an observational study to large-scale population-based

studies including 1 million individuals.

The age range of participants varied across

studies, with some reporting mean or median ages, while others provided

specific age brackets. The mean age of participants ranged from 15 to 80 years.

Certain studies distinguished between patients with and without cirrhosis,

reporting a higher mean age for cirrhotic patients. But some of the studies

didn’t mention any age-related data. Gender distribution was predominantly

mixed, although 2 studies focused on male participants. (Table 3).

Table 3. Key

characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

|

Study Reference

|

Country

|

Study Design

|

Number of Participants

|

Age

|

Gender

|

Limitations of Each Study

|

|

(1)

|

USA

|

Retrospective

cohort

|

16,058

|

Mean age: For

patients without cirrhosis, 60.56 years (standard deviation [SD] = 10.31

years).

For patients with cirrhosis 66.99

years (SD = 7.09 years).

|

Predominantly

male

|

1. Unmeasured

Confounding Factors and Diagnosis Misclassification, 2. Short

Follow-Up Duration, 3. Limited Generalizability, 4. Unvalidated

Definition of Decompensated Cirrhosis

|

|

(2)

|

USA

|

Retrospective cohort

|

137,863

|

Median age: 62 years for metformin

users and 67 years for sulfonylurea users.

|

Both

|

1.

Unmeasured Confounding Factors, 2.

Diabetes Duration Not Considered, 3.

Insulin Effects Not Examined, 4.

Limited Generalizability, 5. Methodological Flaws in Prior Studies

|

|

(3)

|

USA

|

Retrospective

cohort

|

1,890,020

|

Mean age:

56.2 years

|

Both

|

1.

Retrospective Observational Design, 2.

Potential Unmeasured Confounding Factors, 3. Limited Follow-Up Duration, 4.

Generalizability to Non-Veteran Populations, 5. Methodological Limitations in

Prior Studies

|

|

(4)

|

South Korea

|

Comparative cohort

|

201,542

|

>45

|

Both

|

1.

Retrospective Design, 2. Missing Patient Details, 3. Limited Generalizability,

4. Potential Biases, 5. Uncertain Etiology

|

|

(5)

|

USA

|

Retrospective

cohort

|

23926

|

>50

|

Both

|

1.

Observational Study Design, 2. Unmeasured Confounders, 3. Data Limitations

|

|

(6)

|

Taiwan

|

retrospective cohort

|

36,853

|

Mean: 55.09

|

Both

|

1. ICD-10 Code Limitations, 2.

Small Sample Sizes in Minority Groups, 3. Need for Comprehensive Research

|

|

(7)

|

USA

|

retrospective

cohort

|

3,185

|

Mean: 74.8

|

Both

|

1. Ethnic

Specificity, 2. Unaccounted Lifestyle Factors, 3. Insulin Therapy Effects, 4.

Data Management Challenges, 5. Lifestyle Factors and Health Risks, 6. Need

for Comprehensive Research

|

|

(8)

|

China

|

retrospective analysis

|

159

|

Mean:56

|

|

1. Shifts in Diabetes Treatments

Over Time, 2. Unaccounted Health

Behaviors, 3. Lack of Treatment Classification

Data, 4. Retrospective Design, 5. Sample Size and Diversity, 6. Long-Term Effects of Metformin, 7. Interactions with Other Treatments

|

|

(9)

|

Netherlands

|

Population

based cohort

|

207,367

|

Median age:

61

|

Both

|

1. Misclassification

of NAFLD Diagnoses, 2. Lack of

Detailed Lifestyle Data, 3. Small

Sample Sizes

|

|

(10)

|

Japan

|

Observational (cross sectional

study)

|

7

|

Not specified

|

Not specified

|

1.

Small Sample Size, 2. Reliance on Liver Biopsies, 3. Potential Bias from Pharmaceutical Funding,

4. Limited Validation of GLP-1R

Expression

|

|

(11)

|

Taiwan

|

Population

based case control study

|

47,160

|

Mean age:

65.3

|

Both

|

1. Case-Control Design Limitations, 2. Absence of Lifestyle Data, 3. Sample Size Concerns

|

|

(12)

|

Italy

|

Clinical transitional study

|

70

|

28~89

|

Both

|

1.

In Vitro Model Limitations, 2.

Heterogeneity of HCC, 3.

Metformin's Long-Term Effects, 4.

Patient Variability, 5. Need

for Further Research

|

|

(13)

|

Italy

|

Multicenter

retrospective

|

279

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

1. Retrospective Data Bias, 2. Heterogeneity of HCC Patients, 3. Impact of Metabolic Status and

Comorbidities, 4. Need for Prospective

Trials

|

|

(14)

|

Taiwan

|

Retrospective cohort

|

1000000

|

40~60

|

Both

|

1.

Observational Study Design, 2.

Genetic Variability and Unmeasured Confounders

|

|

(15)

|

Australia

|

Retrospective

cohort

|

299

|

40~60

|

Both

|

1. Observational Study Design, 2. Uncontrolled Confounding Factors

|

|

(16)

|

Taiwan

|

Multi center cohort

|

7249

|

Older

|

Male

|

1.

Observational Study Design, 2. Uncontrolled

Confounding Factors

|

|

(17)

|

China

|

Retrospective

|

123

|

15~75

|

Both

|

1. Observational Study Design, 2. Confounding Factors

|

|

(18)

|

Japan

|

Cross sectional

|

478

|

40~80

|

Both

|

1.Observational Study Limitations,

2.Bias and Confounding, 3.Variations

in Patient Care, 4.Sample Size and Patient

Heterogeneity

|

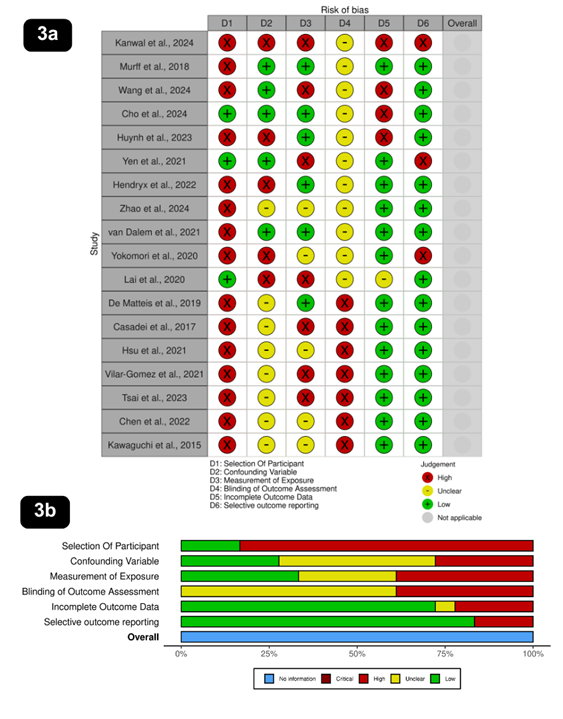

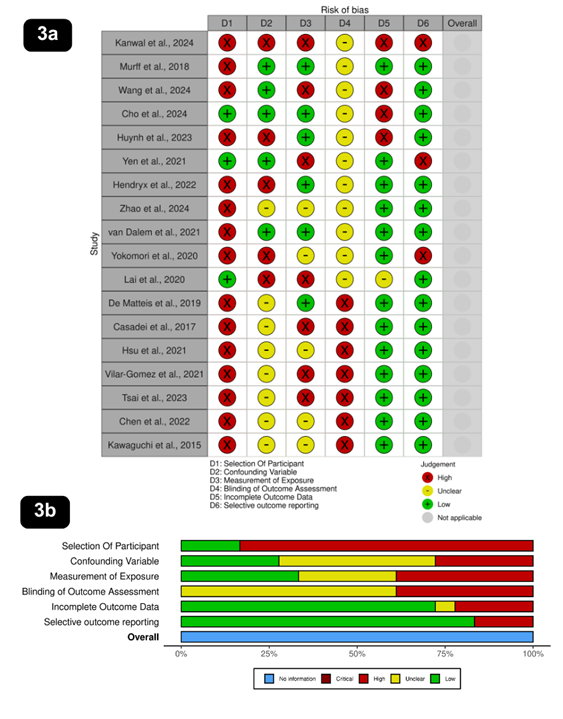

Risk of bias assessment

A systematic risk of bias assessment was

conducted for the 18 studies included in this review, evaluating six key

domains: selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of

exposure, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and

selective outcome reporting (Figure 2).

Among the studies, 15 were classified as

high risk and 3 as low risk for participant selection, indicating a substantial

risk in this domain. Confounding variables were a concern, with 5 studies at

high risk, 5 at low risk, and 8 marked as unclear, reflecting variability in

controlling confounders. Measurement of exposure showed 7 studies at high risk,

6 at low risk, and 5 as unclear, suggesting inconsistencies in exposure

assessment. A significant limitation was blinding of outcome assessment, with

11 studies marked as unclear and 7 as high risk, highlighting a lack of

transparency in blinding procedures. Incomplete outcome data were generally

well managed, with 13 studies classified as low risk, 4 as high risk, and 1 as

unclear, ensuring comprehensive reporting in most cases. Similarly, selective

outcome reporting was well handled, with 15 studies assessed as low risk and 3

as high risk, indicating minimal bias in this area. Overall, while certain

domains, such as blinding and participant selection, posed a high risk of bias,

the handling of outcome data and selective reporting was relatively robust.

Association between anti-diabetic drugs and liver cancer

Key findings of the included studies are

given below (Table 4) according to the different classes of anti-diabetic

drugs.

Recent studies have illuminated the

intricate relationship between antidiabetic therapies and outcomes related to

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Thiazolidinediones have shown a strong negative association with HCC risk, indicating

a potential protective effect (9). Similarly, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2)

inhibitors have been linked to significantly lower mortality risks in HCC

patients, especially those with chronic viral hepatitis (7). Additionally, GLP-1 receptor agonists are

associated with a reduced risk of HCC and hepatic decompensation, suggesting

that their benefits extend beyond diabetes management (1). Conversely, insulin use in individuals with type

2 diabetes and cirrhosis has been associated with an increased risk of all-cause

mortality and severe complications, highlighting the need for vigilant

management in this high-risk group redu(5). Furthermore, metformin therapy has demonstrated

promising outcomes, correlating with improved survival rates in patients with

biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and

compensated cirrhosis, particularly in those with elevated HbA1c levels (15). The combination of metformin and SGLT2

inhibitors warrants further exploration, as their synergistic effects could

enhance patient outcomes (18). While DPP-4 inhibitors suggest a potential

protective effect against HCC, existing studies are primarily observational,

necessitating additional research to establish causative relationships (14). Ultimately, these findings advocate for a

personalized

diabetes management approach that

prioritizes hepatic health, aiming to improve outcomes for at-risk populations.

Figure 3. Risk of bias assessment across included studies. Figure 3a shows

the proportion of studies assessed for various domains of bias, including:

selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of exposure,

blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome

reporting. Each domain is color-coded to represent the assessed level of bias:

Low risk (green), Unclear risk (yellow), High risk (red), Critical risk (dark

red), and No information (blue). Figure 3b (see image below) provides a

study-wise breakdown of risk of bias assessments, allowing a granular

comparison across individual studies.

These assessments were conducted using the ROBINS-I tool (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised

Studies - of Interventions), which is designed to evaluate the risk of bias in

non-randomized intervention studies. The visual summaries aid in identifying

methodological limitations and potential biases that may influence the

reliability of the reported outcomes (1-18).

Table 4. Association between

Antidiabetic drugs and liver cancer.

|

Drug/Management

|

Findings

|

References

|

|

Thiazolidinediones

|

- Associated with a negative correlation between their use and

the risk of developing HCC in type 2 diabetes patients.

- For each additional year of use, a lower risk of HCC was

observed.

- HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.53–0.84 for each additional year of use.

|

(11)

|

|

Sodium-Glucose

Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors

|

- The initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with HCC

resulted in lower mortality risk.

- Longer duration of SGLT2 use was linked to greater survival

benefits.

- Notably beneficial in patients with chronic viral hepatitis.

- Adjusted HR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.60–0.86.

|

(7)

|

|

GLP-1

Receptor Agonists

|

- Linked to a significantly reduced risk of developing HCC in

type 2 diabetes patients.

- May help in preventing hepatic decompensation in this

population.

- Suggests protective mechanisms against liver complications.

- HR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45–0.75.

|

(1)

|

|

Metformin

|

- Associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with biopsy-proven

NASH and compensated cirrhosis.

- Significant reduction in risks of death and hepatic

complications.

- Particularly effective in patients with HbA1c levels above

7.0%.

- RR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.50–0.84; especially effective with HbA1c

>7.0%.

|

(15)

|

|

Insulin

(in Type 2 Diabetes with Cirrhosis)

|

- Associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality and

liver-related complications.

- Increased prevalence of severe hypoglycemia and cardiovascular

events observed.

- Indicates a need for careful treatment consideration and

monitoring.

- HR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.18–1.70.

|

(5)

|

|

Dual

Therapy (Metformin and SGLT2i)

|

- Suggested for future studies to validate the efficacy in larger

and more diverse populations.

- Potential for improving treatment outcomes when tailored to

individual patient needs.

- Emphasizes comprehensive patient assessments.

|

(4)

|

|

DPP-4

Inhibitors

|

- Observed potential protective effects against HCC.

- Causal relationships remain to be established due to the

observational nature of current studies.

- Further research is needed to confirm findings and explore

underlying mechanisms.

- Reported HR ranges from 0.70 to 0.85 in subgroup analyses.

|

(1)

|

Influencing factors for hepatocellular carcinoma due to diabetes management

The summary below emphasizes the factors

influencing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) within the framework of diabetes

management. Key determinants include patient demographics, such as age, gender,

and general health status, which notably affect clinical outcomes (14).

Additionally, comorbid conditions like chronic liver diseases—specifically

cirrhosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—have been identified as

contributing to the elevated risk of HCC (13, 27). The therapeutic impact of

antidiabetic medications, including metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors,

demonstrates potential benefits in improving patient prognosis and reducing

mortality associated with HCC (14, 26). Moreover, lifestyle factors,

including physical activity and dietary habits, play a crucial role in

augmenting the effectiveness of treatment regimens and influencing disease

progression (17, 18). Additionally, the selection of therapeutic interventions,

such as transarterial chemoembolization and its

integration with other treatment modalities, has been shown to significantly

impact patient survival (26). Collectively, these findings underscore the

necessity for personalized treatment strategies and the importance of closely

monitoring metabolic health to diminish the risk of HCC among individuals with

diabetes (14, 27).

Discussion

The relationship between anti-diabetic

drugs and liver cancer, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), has gained

significant attention in recent years. Our systematic review provides a

thorough analysis of the relationship between anti-diabetic drugs and liver

cancer risk, progression, complications, treatment outcomes, and prognosis. The

studies included in our review originated from diverse geographic locations,

with the USA (5) and Taiwan (4) contributing the most research. Additionally,

this review integrates evidence from various study designs, including

retrospective cohort studies, population-based analyses, and preclinical

experimental research that provide insights into the complex interplay between

diabetes management and liver cancer risks.

Among the anti-diabetic medications

reviewed, Metformin consistently shows the strongest protective effect against

HCC, beyond its role in blood sugar control. Patients with type 2 diabetes and

cirrhosis treated with metformin exhibit a significant 56% reduction in HCC risk compared to those using sulfonylureas (2). Furthermore, metformin serves a protective role

in reducing the risk of hepatic decompensation and death in type 2 diabetic

patients with HbA1c >7.0% (15) Metformin provides long-term liver protection and

reduces complications in type 2 diabetic patients with chronic hepatitis C

(CHC) who achieved sustained virological response (SVR) after antiviral therapy

(16). Metformin exerts its beneficial effects through

modulation of metabolic pathways. For example, It

enhances AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) that decreases metabolic and

survival pathways of tumor cells. It also inhibits

mTOR, which suppresses tumor growth pathways and

upregulates SIRT3, which improves mitochondrial function and reduces oxidative

stress. Additionally, the reduction of HIF-1α limits hypoxia-driven tumor progression. Ultimately, these mechanisms lead to

decreased tumor cell proliferation (12,13).

A separate study found that low-dose

metformin inhibits HCC cell migration by reducing interleukin-8 (IL-8)

secretion, which reduces

inflammation and plays a role in tumor progression

and metastasis. This suggests that metformin might help slow cancer spread, potentially improving prognosis and quality of life for HCC patients (8). Additionally, metformin has shown enhanced

progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates in patients

taking Sorafenib, a tyrosine kinase

inhibitor (TKI) used as targeted

therapy for advanced HCC, suggesting its potential in both prevention and

adjunctive cancer therapy (13). A study found that trans-arterial

chemoembolization (TACE) combined with metformin improves HCC prognosis in type

2 diabetes patients, enhancing treatment efficacy and survival (17).

Similarly, thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are

strongly associated with reduced risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(NAFLD) and HCC (9,11). Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), such as pioglitazone

and rosiglitazone, with longer duration of use, may reduce the risk of

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) through multiple mechanisms, primarily by

improving insulin resistance, reducing inflammation, and exerting direct anti-tumor effects (11). It activates peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), which

enhances insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues and reduces

hyperinsulinemia, which decreases hepatocyte proliferation and carcinogenesis (19).

GLP-1 receptor agonists have potential in

reducing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risks and hepatic decompensation

despite their well-known benefits in glycemic control

and cardiovascular protection, adding another dimension to their clinical

significance (3). A study also highlights the significant role of

GLP-1 receptor agonists in reducing the risk of cirrhosis and HCC, particularly

in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic

liver disease (MASLD) (1). These drugs modulate fat metabolism, reduce fat

in liver parenchyma, and decline the progression of fibrosis, have

anti-inflammatory effects, and exert hepatic protection (1,9).

The long-term use of DPP-4 inhibitors

lowers the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with type 2

diabetes and chronic HCV infection by preventing CXCL10 truncation that

diminishes HCV viral load and enhances immune response. So, it could indeed be

a valuable second-line therapy after metformin for patients with both diabetes

and chronic HCV (14). But a study shows GLP-1 receptor agonists are

superior in terms of reducing cirrhosis progression and related complications

compared to DPP-4 inhibitors (1).

In contrast, studies based on SGLT2

inhibitors (SGLT2i) reveal a bit of controversial information. One study shows

that longer duration of SGLT2 inhibitor use is associated with greater survival

benefits through mechanisms like reducing

systemic inflammation, improving

metabolic control, and potentially

limiting liver fibrosis or tumor progression (7). Again, the combination of metformin and SGLT2

inhibitor appears to have a beneficial effect in reducing complications and

morbidity in HCC (5). On the other hand, another study reveals that

SGLT2 inhibitors did not significantly reduce HCC risk in patients with NAFLD

and T2DM. But the benefit is population dependent because SGLT2 inhibitors have

a promising positive effect in HCC risk reduction in patients with HCV

infection (4).Although insulin therapy is effective in

controlling blood glucose, its use in cirrhotic patients may lead to adverse

outcomes like higher mortality, liver complications, cardiovascular events, and

hypoglycemia. As hyperinsulinemia worsens the

condition of cirrhosis and HCC, administration of exogenous insulin in type 2

diabetic patients who have more or less insulin resistance results in a

profound increase in blood insulin level that deteriorates the metabolic

condition of the liver and enhances tumorigenesis (6,13). Therefore, instead of insulin therapy, other

medications such as metformin, Thiazolidinediones or GLP-1 receptor agonists

are efficacious to reduce the risk of NAFLD, cirrhosis, and HCC (9,13).

Key recommendations

Recommendations from the included studies

with their key insights are given in the table below (Table 5).

Despite potential evidence pointing towards

a possible association between antidiabetic drugs and the risk of liver cancer,

the inconclusiveness of available data emphasizes the need for further

comprehensive research. Future studies should consider larger and more diverse

study populations to validate the generalizability of findings. Randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies should be prioritized

to confirm the causal relationships between antidiabetic drugs and HCC risk

reduction. Again, mechanistic studies can be done further to delve into the biological, molecular, or

physiological mechanisms of how different antidiabetic drugs influence liver

cancer development.

For high-risk cirrhotic patients where

insulin is associated with increased mortality and hepatic complications,

alternative management strategies should be explored (20). These may include the cautious use of metformin

(with liver function monitoring), SGLT2 inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptor

agonists—agents that have demonstrated potential hepatic benefits in

non-cirrhotic populations (21). In patients with compensated cirrhosis,

individualized treatment regimens and close monitoring of glycemic

control, liver enzymes, and nutritional status are essential (20). Consultation with hepatologists and

endocrinologists is also advised for optimizing therapy in this complex patient

group.

Table 5. Key

recommendations of selected studies.

|

References

|

Recommendations

|

Key insights

|

|

(5)

|

Future

research should involve larger and more diverse populations to validate the

benefits of dual therapy; explore the long-term safety of treatments.

|

To enhance

the applicability and robustness of findings across different demographic

groups.

|

|

(9)

|

Future

studies should adopt prospective designs to understand the long-term effects

of TZDs on liver health; include lifestyle factors in analyses.

|

To achieve

a nuanced understanding of TZD effects and improve treatment strategies for

patients.

|

|

(3)

|

Future

research should focus on prospective trials to explore the long-term effects

of GLP-1 receptor agonists; consider diverse patient populations.

|

To

validate effectiveness and explore the mechanisms behind GLP-1 RAs in various

demographics.

|

|

(1)

|

Highlights

the significance of early treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists and

encourages future research on long-term outcomes across varied populations.

|

To promote

early intervention strategies to improve liver health outcomes among at-risk

patients.

|

|

(11)

|

Conduct

further studies to explore the protective effects of TZDs against liver

cancer; include lifestyle factors in future analyses.

|

To

establish a causal relationship and better understand the protective role of

TZDs in liver cancer risk reduction.

|

|

(15)

|

Emphasizes

the need for randomized trials to clarify metformin's role; monitor patients

for lifestyle changes.

|

To

establish clear causal links and improve management strategies for

diabetes-related liver conditions.

|

Further works should highlight the

following points-

1. Larger and Diverse Studies: Future

research should involve larger and more diverse populations to enhance the

generalizability of findings, particularly regarding the efficacy of metformin

and SGLT2 inhibitors in improving liver health outcomes (5).

2. Long-term Prospective Research: There is a need for prospective studies to investigate the long-term

effects of thiazolidinediones (TZDs) and their interactions with lifestyle

factors to better understand their role in liver health (9).

3. Evaluation of GLP-1 Agonists: Research should focus on the long-term effects of GLP-1 receptor

agonists across various demographics to confirm their protective benefits

against liver complications (3).

4. Early Intervention: Emphasizing early treatment with GLP-1

receptor agonists for at-risk patients can significantly improve liver health

outcomes (1).

5. Establish Causal Links for TZDs: More studies are needed to explore the protective effects of TZDs

against liver cancer, aiming to establish clear causal relationships (11).

6. Randomized Trials for Metformin: Conducting randomized controlled trials will help clarify metformin's

protective role in enhancing liver-related outcomes in patients with diabetes (15).

Clinical Implications

The findings from this review underline the

importance of incorporating antidiabetic medications such as metformin, TZDs,

and GLP-1 receptor agonists into diabetes management, not only for glycemic control but also for their potential to reduce the

risk of liver cancer (22–24). These medications, particularly metformin and

GLP-1 receptor agonists, demonstrate significant protective effects against

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), highlighting their dual benefits in both

diabetes management and liver health (25,26). Early intervention with GLP-1 receptor

agonists, especially in at-risk populations, may offer substantial long-term

benefits, potentially reducing the risk of hepatic decompensation and HCC

progression (26,27). Moreover, individualized treatment strategies

based on patient demographics, liver disease severity, and metabolic factors

are essential for optimizing therapeutic outcomes (28). In high-risk patients, such as those with

cirrhosis, careful selection of medications and close monitoring are critical (29). These insights emphasize the need for

personalized, patient-centered approaches that

incorporate both metabolic and genetic factors to enhance treatment efficacy,

minimize adverse effects, and improve overall patient outcomes, particularly in

preventing liver cancer among individuals with diabetes.

Limitations and future directions

This systematic review, while thorough, has

several limitations. Firstly, many of the included studies were observational,

limiting the ability to establish causality between antidiabetic medication use

and liver cancer outcomes. Observational studies are prone to various biases,

such as selection and information bias, which may affect the reliability of the

findings.

Secondly, due to restricted access to

certain databases, we were unable to include relevant studies from platforms

like Google Scholar, potentially missing important research.

Thirdly, the review primarily focused on

observational studies and did not include systematic reviews or meta-analyses,

which could have provided a broader perspective on the topic.

Additionally, small sample sizes in some

studies limited the generalizability of the results and increased the risk of

type II errors.

Lastly, several studies did not adequately

control for confounding factors, such as patient demographics, comorbidities,

and concurrent treatments, which may have impacted the results. The variability

in study designs, drug types, dosages, and follow-up periods also introduced

significant heterogeneity, complicating the synthesis of findings and making

definitive conclusions difficult.

Conclusion

This study underscores the complex and

significant relationship between antidiabetic therapies and hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Evidence suggests

that certain antidiabetic medications, such as thiazolidinediones (TZDs),

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptor agonists,

show promising protective effects against HCC and liver-related complications.

Conversely, insulin use in patients with cirrhosis appears to increase the risk

of mortality and severe complications, highlighting the need for cautious

management in this high-risk group.

Additionally, metformin demonstrates

potential benefits, particularly in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

(NASH) and compensated cirrhosis. However, future research should prioritize

long-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs), well-designed population-based

cohort studies, and mechanistic studies to better validate and clarify the

protective effects of antidiabetic therapies across various liver disease

contexts. Such studies should also assess treatment duration, dosage,

and interactions with coexisting conditions to optimize diabetes management

strategies in patients at risk for liver cancer.

This review also emphasizes the importance

of a personalized treatment approach that takes into account both pharmacologic

therapies and lifestyle factors, aiming to reduce the risk of HCC in

individuals with diabetes. Close monitoring of metabolic health and early

intervention with appropriate medications can significantly improve outcomes in

at-risk populations.

In summary, while current evidence

highlights the potential of various antidiabetic therapies to positively

influence liver health and HCC outcomes, further investigation using rigorous

study designs is crucial to establish clearer causal relationships and refine

clinical strategies for managing diabetes in patients with liver disease.

Author contribution

SN developed the methodology and wrote the methodology section. SN

also conducted data extraction using a predesigned Excel spreadsheet, capturing

key study details, including study design, patient population, type of

antidiabetic medications used, liver cancer outcomes, and major findings.

Additionally, SN oversaw the entire review process and coordinated the writing

of the manuscript. MA independently verified 50% of the extracted data

to ensure accuracy and consistency. MA also wrote the results section,

contributed to the final review of the manuscript, played a role in developing

the study design, and assisted in refining the methodology section. SH contributed

to refining the search strategy, participated in the full-text review process,

and assisted in synthesizing the extracted data. SH also built the tables and diagrams

for the manuscript and helped review the methodology section. MSH independently

conducted the title and abstract screening using Rayyan software, ensuring the

initial selection of studies. MSH also conducted the full-text review for

studies meeting the inclusion criteria and wrote the discussion section. MH independently

verified 50% of the extracted data alongside MA to enhance data accuracy. MH

also contributed to refining the study methodology and participated in

manuscript revisions. AA wrote the introduction section and assisted in

optimizing the search strategy. AA also played a role in screening full-text

articles and contributed to drafting and reviewing the discussion section. TD

independently conducted the title and abstract screening using Rayyan

software, ensuring the initial selection of studies. TD also wrote the

conclusion section and participated in discussions regarding study inclusion

and exclusion criteria. SoN contributed to

writing the discussion section and provided critical revisions to improve

clarity and coherence. SoN also participated in

reviewing the final manuscript to ensure consistency and accuracy. AN played

a role in the quality assessment of included studies and assisted in

synthesizing the extracted data. AN also contributed to reviewing the

discussion and conclusion sections to ensure alignment with the study

objectives. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the

study, provided input on data interpretation, and participated in manuscript

revisions. All authors approved the final version before submission.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest associated with this

paper.

Funding

There is no funding.

References

1. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Li

L, Yang YX, Cao Y, Yu X, et al. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk for Cirrhosis

and Related Complications in Patients With Metabolic

Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. JAMA

Intern Med. 2024 Nov 1; 184(11):1314.

2. Murff HJ, Roumie CL, Greevy RA, Hackstadt

AJ, McGowan LEDa, Hung AM, et al. Metformin use and

incidence cancer risk: evidence for a selective protective effect against liver

cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2018 Sep 1; 29(9):823–32.

3. Wang L, Berger NA,

Kaelber DC, Xu R. Association of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Hepatocellular

Carcinoma Incidence and Hepatic Decompensation in Patients With

Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep 1; 167(4):689–703.

4. Cho HJ, Lee E, Kim SS,

Cheong JY. SGLT2i impact on HCC incidence in patients with fatty liver disease

and diabetes: a nation-wide cohort study in South Korea. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 29;

14(1):9761.

5. Huynh DJ, Renelus BD, Jamorabo DS. Reduced mortality and morbidity associated

with metformin and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes

mellitus and cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023 Dec 1; 23(1).

6. Yen FS, Lai JN, Wei

JCC, Chiu LT, Hsu CC, Hou MC, et al. Is insulin the preferred treatment in

persons with type 2 diabetes and liver cirrhosis? BMC Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec

1; 21(1).

7. Hendryx M, Dong Y, Ndeke JM, Luo J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2)

inhibitor initiation and hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis. PLoS One. 2022 Sep 1; 17(9).

8. Zhao C, Zheng L, Ma Y,

Zhang Y, Yue C, Gu F, et al. Low-dose metformin suppresses hepatocellular

carcinoma metastasis via the AMPK/JNK/IL-8 pathway. Int J Immunopathol

Pharmacol. 2024 Jan 1; 38.

9. van Dalem J, Driessen

JHM, Burden AM, Stehouwer CDA, Klungel OH, de Vries

F, et al. Thiazolidinediones and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and

the Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cohort Study. Hepatology. 2021

Nov 1; 74(5):2467–77.

10. Yokomori

H, Ando W. Spatial expression of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor and

caveolin-1 in hepatocytes with macrovesicular

steatosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020 May

14; 7(1).

11. Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF.

Association of hepatocellular carcinoma with thiazolidinediones use: A

population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2020 Apr 23 ;

99(17):E19833.

12. De Matteis S, Scarpi E, Granato AM, Vespasiani-Gentilucci

U, Barba G La, Foschi FG, et al. Role of SIRT-3, p-mTOR and HIF-1α in

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Affected by Metabolic Dysfunctions and in

Chronic Treatment with Metformin. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar 2; 20(6).

13. Casadei Gardini A, Faloppi L, De Matteis S, Foschi FG, Silvestris N, Tovoli F, et al. Metformin and insulin impact on clinical

outcome in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib:

Validation study and biological rationale. Eur J

Cancer. 2017 Nov 1; 86:106–14.

14. Hsu WH, Sue SP, Liang

HL, Tseng CW, Lin HC, Wen WL, et al. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors Decrease

the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With

Chronic Hepatitis C Infection and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Nationwide Study

in Taiwan. Front Public Health. 2021 Sep 17; 9.

15. Vilar-Gomez E,

Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wong VWS, Castellanos M, Aller-de la Fuente R, Eslam M, et

al. Type 2 Diabetes and Metformin Use Associate With

Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic

Steatohepatitis–Related, Child–Pugh A Cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and

Hepatology. 2021 Jan 1; 19(1):136-145.

16. Tsai PC, Kuo HT, Hung

CH, Tseng KC, Lai HC, Peng CY, et al. Metformin reduces hepatocellular

carcinoma incidence after successful antiviral therapy in patients with

diabetes and chronic hepatitis C in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2023 Feb 1;

78(2):281–92.

17. Chen ML, Wu CX, Zhang

JB, Zhang H, Sun YD, Tian SL, et al. Transarterial

chemoembolization combined with metformin improves the prognosis of

hepatocellular carcinoma patients with type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 2022 Sep 15; 13.

18. Kawaguchi T, Kohjima M, Ichikawa T, Seike M,

Ide Y, Mizuta T, et al. The morbidity and associated risk factors of cancer in

chronic liver disease patients with diabetes mellitus: a multicenter field

survey. J Gastroenterol. 2015 Mar 1; 50(3):333–41.

19. Vella V, Nicolosi ML,

Giuliano S, Bellomo M, Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R.

PPAR-γ agonists as antineoplastic agents in cancers with dysregulated IGF

axis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017 Feb 22; 8(FEB):244472.

20. Puri P, Kotwal N. An

Approach to the Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Cirrhosis: A Primer for the

Hepatologist. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021 Mar 1; 12(2):560.

21. Padda IS, Mahtani AU,

Parmar M. Sodium-Glucose Transport Protein 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors. StatPearls. 2023 Jun 3.

22. Weinberg Sibony R, Segev

O, Dor S, Raz I. Drug Therapies for Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Dec 1;

24(24):17147.

23. Arvanitakis K, Koufakis T, Kalopitas G,

Papadakos SP, Kotsa K, Germanidis

G. Management of type 2 diabetes in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis:

Short of evidence, plenty of potential. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome:

Clinical Research & Reviews. 2024 Jan 1; 18(1):102935.

24. Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the

treatment of type 2 diabetes – state-of-the-art. Mol Metab.

2020 Apr 1; 46:101102.

25. Huynh DJ, Renelus BD, Jamorabo DS. Dual metformin and glucagon-like peptide-1

receptor agonist therapy reduces mortality and hepatic complications in

cirrhotic patients with diabetes mellitus. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 30;

36(5):555.

26. Shabil

M, Khatib MN, Ballal S, Bansal P, Tomar BS, Ashraf A, et al. Risk of

Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonist

treatment in patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024 Dec 1;

24(1):246.

27. Wang L, Berger NA,

Kaelber DC, Xu R. Association of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Hepatocellular

Carcinoma Incidence and Hepatic Decompensation in Patients With

Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep 1; 167(4):689–703.

28. Wazir H, Abid M, Essani B, Saeed H, Khan MA, Nasrullah F, et al. Diagnosis

and Treatment of Liver Disease: Current Trends and Future Directions. Cureus.

2023 Dec 4; 15(12):e49920.

29. Chandok N, Watt KDS.

Pain Management in the Cirrhotic Patient: The Clinical Challenge. Mayo Clin

Proc. 2010; 85(5):451.