Long term clinical outcomes in patients with rectal

adenocarcinoma treated at a Tertiary Care Centre in South India

Amirthvarshan A 1,

Lijeesh A L 1, Roshni S 1*,

Mulla P A 2, Sivanandan C D 1,

Sajeed A 1, Arun Sankar 1, Geethi M H 1, Aleyamma Mathew 3

1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Regional Cancer Centre,

Thiruvananthapuram, India

2 Department of Radiation Oncology, Mangalore Institute of Oncology, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India

3 Division of Cancer epidemiology and Biostatistics, Regional cancer

Centre, Thiruvananthapuram, India

* Corresponding Author: Roshni

S

* Email: roshnisyampramod@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Treatment of rectal adenocarcinoma involves multi-disciplinary approach

which includes radiation, surgery and chemotherapy. Our study aims to assess

the clinical outcomes of patients with rectal adenocarcinoma treated in a

tertiary care centre in South India.

Materials and methods: A retrospective content-based analysis was made of 131 patients

diagnosed and treated for adenocarcinoma rectum in a tertiary care hospital

during the period of 1st January 2014 to 31st December 2015. The primary

objectives were to assess disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival

(OS).

Results: Of the 131 patients, 82 were males and 49 were females with a median

age of 59 years. Stage II and Stage III disease together contributed to 65.6%

of study population. After a median follow up of 105.8 months, the 8-year

overall OS and DFS were found to be 77.2% and 78.8% respectively. In the

univariate analysis, stage of the disease and histology were found to be

significant factors in determining the overall survival (p<0.05).

Multivariate analysis showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma emerged as

significant factor affecting overall survival. About 31 (23.6%) patients showed

disease recurrence. Of the 31 patients, pelvic recurrence occurred in 26%

patients and among the distant metastases, liver was the most common site (33%)

followed by lung (22%).

Conclusion: The disease free survival and overall

survival of our patients were comparable with the available published data.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, Histology, Young adults, Survival rates, Prognosis

Introduction

Rectal cancer had been primarily considered a disease of the elderly,

which mostly occur after the fifth decade of life but younger people aged less

than 50 years diagnosed with colorectal cancer have been on the rise recently

(3). Most of the patients present with locally advanced disease having a 5-year

survival of 73% as per National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) Surveillance,

Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Program of Cancer

Registries (4). But the 5-year survival rate of locally advanced rectal cancer

in India is 40% which is one of the lowest in the world (5).

The standard

treatment in early-stage disease is primary surgery with or without adjuvant

treatment. In locally advanced disease, the standard of care is neoadjuvant

treatment followed by surgery with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. Assessment

of survival is the strongest parameter in oncologic outcomes. The complexity of multidisciplinary

approach and the subtle variability in clinical decision

making warrants periodical scrutiny of treatment profiles.

A study by Patil et al., showed that most of the colorectal cancers

presents at a younger age, with an aggressive histopathology, and with

involvement of both rectum and anal canal (5). There have been only few

epidemiological studies with respect to clinical outcomes of rectal cancer in

India and with its wide cultural and socio-ethnic differences, it is imperative

to assess the demographic and clinical profile that helps in strategic

planning, early diagnosis and efficient treatment modalities. Hence this study

aims to assess the clinical outcomes of patients with rectal cancer treated in

a tertiary care centre in South India.

Materials and methods

A total of 131 patients were diagnosed and

treated from June 1st 2014 to May 31st 2015 in a tertiary

care hospital in South India. This is a retrospective analytical study with

data obtained from the Medical Records in the hospital. It was based on content

analysis where the clinical and histopathological staging, treatment and follow up

details were collected from the case records using a structured proforma.

All rectal carcinoma patients with histology

of adenocarcinoma during the study period were included in the study. Histology

other than adenocarcinoma were excluded from the study. Informed consent was

obtained from all patients and the study was approved by Institutional Review

Board (No: 09/2016/04).

Statistical analysis

All patients (n = 131) were analysed and

follow up data was updated until April 2023. The primary endpoints analysed

were disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). DFS was defined as

the period from the date of registration to the date of locoregional relapse,

distant relapse or death, whichever occurred earlier. OS was defined as the

period from the date of registration to the date of death from any cause. The

statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 20. The data was analysed and

results were tabulated using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were expressed as

mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables as counts and

percentages. Survival curves were

generated using the Kaplan‑Meier method and statistical significance was

assessed using the log‑rank test. The risk for survival was assessed

using cox regression analysis and a p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From June 1st 2014 to May 31st

2015, 131 patients with biopsy proven rectal adenocarcinoma were analysed in

the present study. Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. The median

age of the population was 59 years ranging from 24 to 91 years. There were 82

males (62.59%) and 49 females (37.41%) included in the study. Mid rectal cancer

(defined as tumors residing 5-10cm from anal verge)

was the most common occurring in 51 patients (38.93%) closely followed by lower

rectal cancer (defined as tumors residing <5cm

from anal verge) diagnosed in 45 patients (34.36%) and upper rectal cancer

(defined as tumors residing 10-15cm from anal verge)

in 35 patients (26.71%). Majority had cT3 disease (38.16%) followed by cT2

(30.55%) and cT4 disease (16.03%). With respect to nodal status, 72 patients

(54.96%) had node negative disease. Stage II and Stage III disease dominated

the study population each contributing to 32.82% followed by stage I disease

(27.49%).

High risk factors like obstruction,

perforation, presence of LVE (lymphovascular

emboli)/PNI (Perineural invasion) and inadequate nodal sampling, were present

in 11 patients (8.39%). High-risk pathology like poorly differentiated

carcinoma (2.29%), mucinous adenocarcinoma (12.21%) and presence of signet ring

cells (9.92%) were observed.

Treatment characteristics

Prior to reporting at our centre, 32 patients

(24.42%) received some form of oncological treatment elsewhere. Of the

remaining 99 patients, 82 patients (82.82%) received neoadjuvant

chemoradiation. Pathological Complete Response was seen in 8.39% patients.

Pathologically node-negative disease was observed in 52.7% of patients. About

88 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, of them 75% patients were treated

with mFOLFOX-6 (5-Fluorouracil + Folinic acid + Oxaliplatin) and 14.7% patients

were treated with CAPOX (Capecitabine + Oxaliplatin) regimen.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

|

Characteristics |

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Age |

||

|

<40 |

10 |

7.6% |

|

40-59 |

61 |

46.56% |

|

60-79 |

55 |

42.04% |

|

>80 |

5 |

3.8% |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

82 |

62.59% |

|

Female |

49 |

37.41% |

|

Site of disease |

||

|

Upper |

35 |

26.71% |

|

Mid |

51 |

38.93% |

|

Lower |

45 |

34.36% |

|

Tumour characteristics |

||

|

T1 |

20 |

15.26% |

|

T2 |

40 |

30.55% |

|

T3 |

50 |

38.16% |

|

T4 |

21 |

16.03% |

|

Nodal Status |

||

|

N0 |

72 |

54.96% |

|

N1 |

33 |

25.20% |

|

N2 |

26 |

19.84% |

|

Stage of the disease |

||

|

Stage I |

36 |

27.49% |

|

Stage II |

43 |

32.82% |

|

Stage III |

43 |

32.82% |

|

Stage IV |

9 |

6.87% |

|

High risk factors |

||

|

Obstruction |

1 |

0.76% |

|

Perforation |

1 |

0.76% |

|

LVE/PNI |

4 |

3.05% |

|

Inadequate Lymph Node sampling |

5 |

3.81% |

|

Histology |

||

|

Well Differentiated |

21 |

16.04% |

|

Moderately Differentiated |

78 |

59.54% |

|

Poorly differentiated |

3 |

2.29% |

|

Mucinous |

16 |

12.21% |

|

Signet ring cell |

13 |

9.92% |

|

Radiotherapy |

||

|

NACTRT |

83 |

63.35% |

|

Adjuvant CRT |

17 |

12.97% |

|

SCRT |

3 |

2.22% |

|

Palliative RT |

6 |

4.58% |

Abbreviations:

LVE - lymphovascular emboli; PNI - Perineural

invasion; NACTRT – Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; CRT – chemoradiotherapy; SCRT

– short course radiotherapy; RT – Radiotherapy.

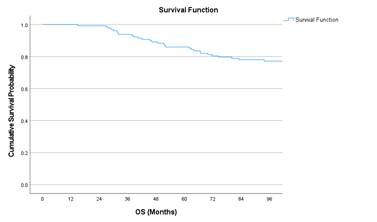

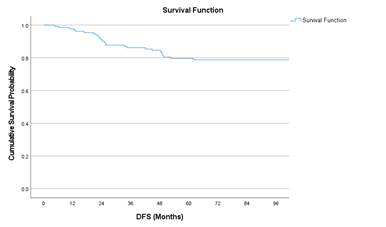

The median follow up was 105.8 months (16.6

to 182.6 months). The 8-year OS and DFS was shown to be 77.2% and 78.8%

respectively. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan Meier curves for 8-year DFS and OS in

our study.

Figure 1. Kaplan Meier

curves of 8-year DFS and OS.

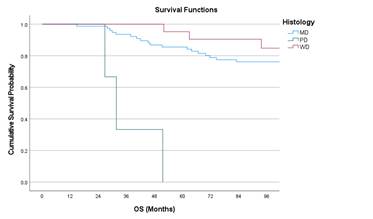

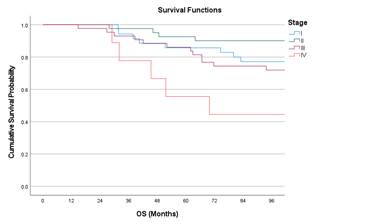

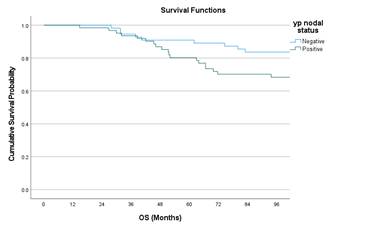

Tables 2 and 3 show the cumulative survival

probabilities of OS and DFS with respect to stage, sex, site of disease,

histology, and various chemotherapy regimens respectively. Figure 2 shows the

Kaplan Meier curves of OS with respect to stage, histology and nodal status.

Table 2. Survival probability with respect to OS.

|

Variables |

Cumulative Survival Probability (%) |

P-value |

|

|

Stage |

I |

77.1 |

0.009 |

|

II |

90.1 |

||

|

III |

71.9 |

||

|

IV |

44.4 |

||

|

Sex |

Female |

70.5 |

0.101 |

|

Male |

81.1 |

||

|

Age |

<50 |

72.1 |

0.371 |

|

>=50 |

78.9 |

||

|

Site |

Lower |

81.0 |

0.756 |

|

Mid |

76.2 |

||

|

Upper |

74.1 |

||

|

Histology |

MD |

76.2 |

<0.001 |

|

PD |

0.0 (all

died) |

||

|

WD |

84.8 |

||

|

Prior

Treatment |

Treated

elsewhere |

84.4 |

0.258 |

|

No Treatment |

74.7 |

||

|

Pathological

Nodal Status |

Negative |

83.6 |

0.063 |

|

Positive |

68.3 |

||

|

Adjuvant

Chemotherapy |

CAPECITABINE |

100.0 |

0.043 |

|

CAPOX |

61.5 |

||

|

FOLFOX |

81.4 |

||

|

Palliative

Chemotherapy |

CAPOX |

66.7 |

0.007 |

|

FOLFOX |

0.0 (all

died) |

||

|

5-FU+LV |

100.0 |

||

Abbreviations:

MD- Moderately Differentiated; WD- Well Differentiated; PD- Poorly

Differentiated; 5FU + LV – 5-Flourouracil + Leucovorin; mFOLFOX-6

(5-Fluorouracil + Folinic acid + Oxaliplatin); CAPOX (Capecitabine +

Oxaliplatin).

Table 3. Survival probability with respect to DFS.

|

Variables |

Cumulative Survival Probability (%) |

P-value |

|

|

Stage |

I |

80.3 |

0.775 |

|

II |

80.8 |

||

|

III |

73.7 |

||

|

IV |

88.9 |

||

|

Sex |

Female |

73.0 |

0.116 |

|

Male |

82.4 |

||

|

Age |

<50 |

75.4 |

0.434 |

|

>=50 |

80.0 |

||

|

Site |

Lower |

75.0 |

0.592 |

|

Mid |

77.3 |

||

|

Upper |

85.7 |

||

|

Histology |

MD |

73.8 |

0.391 |

|

PD |

66.7 |

||

|

WD |

85.7 |

||

|

Prior

Treatment |

Treated

elsewhere |

77.6 |

0.928 |

|

No Treatment |

79.2 |

||

|

Pathological

Nodal Status |

Negative |

75.0 |

0.473 |

|

Positive |

81.7 |

||

|

Adjuvant

Chemotherapy |

CAPECITABINE |

77.8 |

0.904 |

|

CAPOX |

76.2 |

||

|

FOLFOX |

80.2 |

||

|

Palliative

Chemotherapy |

CAPOX |

66.7 |

0.459 |

|

FOLFOX |

0.0 (all

died) |

||

|

5-FU+LV |

100.0 |

||

Abbreviations:

MD- Moderately Differentiated; WD- Well Differentiated; PD- Poorly

Differentiated; 5FU + LV – 5-Flourouracil + Leucovorin; mFOLFOX-6

(5-Fluorouracil + Folinic acid + Oxaliplatin); CAPOX (Capecitabine +

Oxaliplatin).

Figure 2. Kaplan Meir curves of OS with respect to Stage, Nodal status, and

histology

Univariate analysis showed stage IV had worse

outcomes compared to stage I (Hazard ratio (HR) 3.19; p = 0.042) and poorly

differentiated adenocarcinoma had worse OS compared to moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma (HR 14.94; p = <0.001). Multivariate cox

regression analysis showed poorly differentiated histology is associated with

poor OS with an HR 9.47 (p = 0.003). Table 4 and 5 shows the univariate

analysis with respect to OS and DFS respectively. Table 6 shows the multiple

cox regression analysis affecting OS.

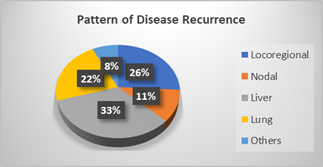

Figure 3 shows the pattern of recurrence

after radical treatment with locoregional recurrence of 26% and among the

distant sites, liver metastasis contributes to 33% followed by lung (22%),

non-regional nodes (11%) and other sites (8%) which includes bone, brain and

adrenals.

Discussion

Colorectal cancer has witnessed a staggering rise in its incidence and

parallelly the evolution of surgical and chemoradiation techniques have

improved the survival of the patients. In general, women tend to have lower

incidence and higher survival in colorectal cancer (6). Losurdo et al.,

published a gender focussed analysis of long-term outcomes of colorectal cancer

that revealed a higher 5-year (86.9% vs 80.5%) and 10-year survival (80% vs

73.3%) for women compared to men (7). This contrasts with our study where no

statistically significant survival differences were seen between men and women.

Siegel et al., reported rising incidence rates of colorectal cancer in

younger population (less than 50 years) in western countries over the last 2

decades (8). A retrospective analysis in an Indian population showed that

around 21% of patients with colorectal cancer were less than 40 years (9). Hong

et al., showed that the lowest 5-year OS and DFS were seen in age group less

than 40 years (62.5% and 52.1% respectively) (10), similar to our study where a

statistically non-significant trend of lower survival rates were seen in

patients less than 50 years.