Comparative study

of virtual and traditional teaching methods on the theoretical course of ECG in

medical students of emergency department

Seyyed Mahdi Zia Ziabari 1, Zoheir Reihanian 2,

Masoumeh Faghani 3 *, Nazanin Noori Roodsari 4, Ashkan

kheyrjouei 4, Rasoul Tabari Khomeiran 5, Ehsan

Kazemnezhad Leyli 6

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Guilan

University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2 Road Trauma Research Center,

Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical

Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3 Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Guilan

University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4 Clinical Research Development Unit, Poursina Hospital, School of

Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5 Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and

Midwifery, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Guilan University of

Medical Sciences

6 Department of

Biostatistics, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical

Sciences, Rasht, Iran

*Corresponding Author: Masoumeh

Faghani

* Email: mfaghani@gums.ac.ir

Abstract

Introduction: The emergency ward is one of the most important parts of the hospital,

where people's activities can have many effects on the performance of other

wards of the hospital and the satisfaction of patients. Changing lifestyle and

transformation of cyberspace into one of the pillars of modern life has had a

great impact on learning and teaching methods. To compare the level of theoretical emergency learning in medical

students with two virtual and traditional methods.

Materials

and Methods: This quasi-experimental study was conducted on 88 medical students who

started their emergency rotation in two hospitals of Guilan University of

Medical sciences in 2021. Both groups participated in the same exam before and

after the basics of electrocardiogram (ECG), normal ECG, types of blocks,

diagnosis of MI and arrhythmias education. After collecting the information

from the questionnaires, the data analysis was performed via SPSS software with

a significant P<0.05.

Results: Out of 88 students, 56.8% were female, and 43.2% were male. The mean

and median knowledge score before and after education was statistically

significant in two groups (P<0.001). The virtual group represented a higher

average score of knowledge than the traditional group. The student’ grade point

average affected the result of the score after education (P=0.019, β =0.234).

Conclusion: The use of virtual education methods in combination with traditional

methods might help to improve the learning process and knowledge of medical

students in emergency department.

Keywords: Clinical education, WhatsApp, Emergency course, Medical students

Introduction

Clinical

education is important for medical students' curriculum (1). Medical students learn in theory

and bedside in hospitals. Based on the curriculum, students enter the different

clinical departments and pass their education periods in the form of

traditional classes of theory and clinical rounds (2).

Correct

treatment in the emergency ward has an effect on the satisfaction of patients

and the function of another ward of the hospital (3). The admission of people in the

hospital often happens in the emergency ward for their needs and urgent care,

so understanding their problems in this ward is essential (4). In addition, in the emergency

ward, the student faces a large volume of clients with different clinical

complaints, stable and unstable problems, and a wide range of acute and chronic

diseases, so it is necessary to receive related training to deal with them (5). During this part of the medical

student's curriculum, under the supervision of emergency medicine faculty

members, they will learn how to take a history, examine and perform diagnostic

and therapeutic procedures (6). Generally, they learn the main

approach for treatment in an emergency situation, pay attention to the

patient's main complaint, and acquire necessary abilities to face common

referrals.

Clinical

learning in general medicine is divided into two parts. In physiopathology,

students focus on learning about the diagnosis and pathology of diseases. In

the internship and intership, courses focus on the management and treatment of

the disease (7). Hospital-based clerkship is a good

opportunity for medical students to learn treat patients by combining

theoretical and clinical knowledge in the hospital environment under the

supervision of professors (6). The Covid-19 pandemic provided an

opportunity for professors to make better use of virtual education and teach

virtually where the presence of students in the hospital is not required (8,9).

In

the learning process, teaching and learning are interdependent. Effective

teaching can increase the quality of learning in students (10). Introducing new approaches and attitudes to education, including

blended learning (BL), can be essential in resolving this issue. BL introduced

as a learning method includes traditional and a variety of methods with

specific technologies. BL is a combination of different methods of

communication with technologies such as electronic learning (e-learning),

e-performance support, and knowledge management practices for providing

education (11,12). BL was first formally introduced by Marsh in 2003. Some consider BL as a

combination of traditional and e-learning methods. Researchers showed that it

as a suitable approach to achieve the desired learning goals by using

appropriate technology and tailored to learning styles (13). Nowadays, virtual e-learning is considered the most advanced educational

method that uses advanced technologies through electronic services (14,15).

The hospital environment is one of the most interactive

work environments(16). The interactions between health workers with patients and themselves can

lead to learning and experience of human resources (17). So, learning is the way to create student work and improve efficiency in

an organization like a hospital. Since an organization can achieve its goals

through capable employees, and it might enhance through learning. In addition, the prevalence

of heart patients in the emergency ward is noticeable. It is necessary for

students to learn the basics of electrocardiogram (ECG), normal ECG,

types of blocks, diagnosis of MI and arrhythmia in order to examine heart

patients who go to the emergency ward of the hospital. Therefore, due to the high importance of learning and achieving the best

method of ECG education, we conducted a study to compare virtual and

traditional education of theoretical knowledge of ECG in medical students of the

emergency ward.

Materials and Methods

Data

collecting

This

quasi-experimental study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Guilan

University of Medical Sciences (number: IR.GUMS.REC.1399.548). The inclusion

criteria were: 1- Medical students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences who

have passed the pre-internship exam. 2- Signing the consent form to participate

in the study. Participating are 88 medical students in their 6th educational

years. The sample size was designed with 5% error probability, 95% reliability

and 0.5 relative frequency based on the results of the study by Shaw et al(18). The medical students started their

emergency medicine rotation in Poursina and Razi hospitals, in the second

semester 2020-2021.

Based

on the study design, these medical students divided randomly in two traditional

and virtual education groups. The basics of electrocardiogram (ECG), normal ECG,

types of blocks, diagnosis of MI and arrhythmia were taught in traditional and

virtual classes for two traditional and virtual groups of interns in the

emergency ward. The first group (traditional education=44), which included

students that entered the emergency unit in three consecutive courses, was

first given personal and educational information. Then, they were taught in a

classroom, where students sat together for one session and attended an ECG

analysis class. Several ECGs were provided to the students and explained in

groups by solving problems. For the second group (virtual: n=44), which was the

students of next three educational courses (one month after traditional group),

the educational materials and slides related to the ECG were provided in the

WhatsApp group (a messaging application).

The

research tool was a questionnaire that designed for this research.

Questionnaire questions were designed as multiple choice based on the diagnosis

of normal ECG and emergency heart diseases. The faculty members of medical

schools in Guilan University of Medical Sciences designed this two-part

questionnaire. The first part of questionnaire included medical student’s

demographic such as age, gender, grade point average of previous years of

students. The second part of

questionnaire was consisted fifteen questions about student knowledge related

to normal ECG,

types of blocks, diagnosis of MI and arrhythmia. Before and three days after the education, the students of each group

were tested via the same questionnaire.

The

content validity of questionnaire was approved via the opinions of a panel of

10 experts of faculty members. Using Lawshe rule of content validity; all items

had a value more than 0.62. Also all questions had a Content Validity Index (CVI) of 90% or higher.

The maximum score of student awareness was between 0 to 8. The scores below

33.3% were considered poor, between 33.3% to 66.6% as average, and scores above

66.6% as excellent knowledge category.

Statistical

analysis

The

data were analyzed using SPSS. The mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum and

maximum with a 95% confidence interval (CI) used to determine the learning rate

of medical students in the two educational groups. We used the frequency and

percentage to determine of learning status (poor, moderate, good). Paired

T-test was done to compare the scores before and after the test, and

Independent T-test was done to compare the score changes. Analysis of

covariance was used to determine the difference of two groups by controlling

the variables of grade point average, previous score, gender, and age group.

Also, the Chi-square test was used to compare the performance of learning

status with a significant level of P <0.05.

Results

Data

from demographic part of questionnaire revealed that the medical students had

an age range of 24-26 years (mean 24.5±0.66), 43.2% of males (n= 38), 56.8%

females (n = 50). There was no significant difference in the frequency

distribution of gender (P=0.667) and age (P=0.131) between two studied groups with Chi Square test.

Because the number of medical students introduced to the ward is determined

directly by the medical school, all students were included in the study.

The mean students' grade point average (GPA) was 15.1 ± 4.35 in traditional and

15.1 ± 34.27 in virtual groups. Independent t test revealed that there were not

statistically significant differences between the mean of GPA in the medical

students of two groups (P=0.808).

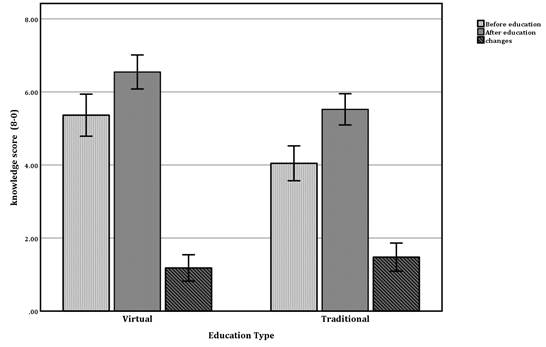

Mann Whitney U Test was used for comparison of

knowledge score before and after three days of education in two groups (Figure

1). A statistically significant

differences was found between groups (P= 0.001) and in each group (P<0.001).

The virtual group, either before or after education, illustrated a higher mean

knowledge score. In both virtual groups and traditional education, education

had a significant effect on the knowledge (P<0.001). The incremental changes

in the traditional group (27.1 ± 48.1) were slightly more than in the virtual

group (19.1 ± 18.1), but this difference was not statistically significant

(P=0.168). However, a significant difference was seen in the percentage of

learning score changes in the traditional method compared to the virtual group

(P=0.041) (Table1).

Discussion

The last few decades have seen a shift from traditional medical

education to online education, virtual networks or e-learning (19). Distance or online education has

been used as an important educational feature in different countries in the

past years (20,21) and according to statistics, almost

30% of students of USA have used distance education courses during their

bachelor's degree (22), but in reality this type of

education in medical education not widely used in some country.

In this study, the experiences of clinical medical students in

e-learning were conducted through social media training via WhatsApp application, which is a new approach to teaching in the

medical school of Guilan University of Medical Sciences during the COVID-19

pandemic. According to the results, the post test scores of medical students

have increased significantly in both groups. It seems that education alone is

effective at the level of knowledge of clinical medical students. Of note, the

knowledge’s score of clinical medical students who participated in virtual

groups was higher than those who received a traditional education (face to

face). In the current study, it was shown that changes in knowledge scores in

male students were more in the virtual group compared to the traditional

one.

Contrary to our study, researchers showed that the score of using

the first principle of education in the traditional educational group was

increased significantly from the virtual educational group (23). Of note, learning is a personal

characteristic, and people have own progress in learning according to their

abilities, so it seems that there is a difference in the score of the first

principle of education in e-learning and traditional education group. Koenigs

et al., stated that students' attitudes toward the learning environment affect

behaviors and the quality of learning outcomes (24). Also, other researchers found that

if the first principle of education is used in e-learning, that could motivate

learners (25). Other study showed that e-learning

could facilitate the learning process (26). According to similar studies the

result of present study suggested the blended method as the most effective one

to improve learning quality (27).

Researchers represented that the traditional teaching method is

reliable for achieving educational goals. The new generation of medical

students have access to high standards and valuable digital resources. New

teaching methods and e-learning alone are not a solution for teaching skills.

So, the traditional learning method mixed with e-learning may help student

learning process (28) and the digital valuable resources

can be well used as a combined learning strategy. Because virtual education has

provided a new environment for learning and reduces traditional educational

limitations such as time and place limitations (29). Therefore, the virtual training

method might be useful for people who do not have enough time for face-to-face

training.

Indeed, Wu et al. results showed a significant difference in the

score of students in the theoretical courses. The results of their study

indicate that the kind of virtual education, the use of interactive animations

due to the activities involving students in education have a better impact on

the understanding of the scientific content, and promote their knowledge (30). Other researchers suggested that

e-learning environments may use as part of blended learning and improve of

clinical skills quality (31). In contrast to our results, some

studies revealed that there was no significant difference in the mean of total

scores before education between the virtual and traditional groups (32).

It is expected that virtual education can partially replace the

traditional method of providing theoretical knowledge but not clinical

knowledge and skills (33). In this era, there is a great

emphasis on life time learning and effective education. Social networks and

E-learning resources in medical education facilitate the learning process for

medical professionals, so the effective use of these technologies in medical

education might help achieve valuable results (34,35). The availability, the independency

of time, and the place of e-learning have led to its widespread use by

students. It noted that the pervasiveness of e-learning requires contexts and

infrastructures, the preparation of which requires time, money, and extra

planning (35).

Conclusions

According to the results of this

study, the average and mean score of knowledge in the medical students who

participated in WhatsApp groups was significantly higher than others who had

received traditional training. It seems that the virtual education method in

combination with the traditional may improve the learning process in medical

students. It seems that e-learning has a significant role in learning

theoretical courses in the future, but it may not be an entire replacement for

practical and face-to-face learning. So, it suggests that a combined approach

(traditional and e-learning) will be the most appropriate method for future

medical education.

Author contribution

SMZZ conceptualization, writing - review & editing, ZR

assistant researcher, MF writing - review & editing, NNR

methodologist/assistant researcher, AK data curation, writing - original

draft, RTK assistant researcher, EKL methodologist, assistant

researcher. All authors confirmed the final version of the paper.

Ethical approval and Funding

This work was supported by the Guilan University of Medical

Sciences (Ethic numbers:

IR.GUMS.REC.1399.548). No funding was received for research, authorship

and the article publication.

Conflict of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Vice Chancellor for Technology Research of

Guilan University of Medical Sciences for approving of this research.

References

1. Dreiling K, Montano D, Poinstingl H, Müller

T, Schiekirka-Schwake S, Anders S, et al. Evaluation in undergraduate medical

education: Conceptualizing and validating a novel questionnaire for assessing

the quality of bedside teaching. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):820–7.

2. Kim RH, Mellinger JD.

Educational strategies to foster bedside teaching. Surgery. 2020;167(3):532–4.

3. Hemmati F, Mahmoudi G,

Dabbaghi F, Fatehi F, Rezazadeh E. The factors affecting the waiting time of

outpatients in the emergency unit of selected teaching hospitals of Tehran.

Electron J Gen Med. 2018;15.

4. De Freitas L, Goodacre

S, O’Hara R, Thokala P, Hariharan S. Interventions to improve patient flow in

emergency departments: an umbrella review. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(10):626–37.

5. Seefeld AW. Lessons

learned from working in emergency departments in Cape Town, South Africa: a

final-year medical student’s perspective. SAMJ South African Med J.

2007;97(2):78–9.

6. Berger TJ, Ander DS,

Terrell ML, Berle DC. The impact of the demand for clinical productivity on

student teaching in academic emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med.

2004;11(12):1364–7.

7. Yari J, Alizadeh M,

Khamenian Z, Ghasemie M. Compatibility of the Curricula of Public Medicine

Internship and Apprenticeship Programs with General Practitioners’ Roles and

Responsibilities. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2017;14(1).

8. Ottinger ME, Farley LJ,

Harding JP, Harry LA, Cardella JA, Shukla AJ. Virtual medical student education

and recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In: Seminars in Vascular Surgery.

Elsevier; 2021. p. 132–8.

9. Andalib E, Faghani M,

Heidari M, Tabari Khomeiran R. Design of vestibules as transitional spaces in

infection control: Necessity of working space changes to cope with communicable

infections. Work. 2022;72(4):1227–38.

10. Nasiri E, Asgari F,

Faghani M, Bahadori MH, Mohammad Ghasemi F, Hosseini F, et al. Effective

teaching, an approach based on students’ evaluation. Res Med Educ.

2008;1:39–44.

11. Shahviren A, Zavvar T,

Ghasemzadee A, Hazratian F. Feasibility assessment of implementing blended

learning in health and treatment network based on ISO 10015 requirements. Iran

J Med Educ. 2016;16:63–71.

12. Garrison DR, Vaughan ND.

Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines.

John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

13. Blieck Y, Ooghe I, Zhu

C, Depryck K, Struyven K, Pynoo B, et al. Consensus among stakeholders about

success factors and indicators for quality of online and blended learning in

adult education: a Delphi study. Stud Contin Educ. 2019;41(1):36–60.

14. Nicoll P, MacRury S, Van

Woerden HC, Smyth K. Evaluation of technology-enhanced learning programs for

health care professionals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res.

2018;20(4):e9085.

15. Al Shorbaji N, Atun R,

Car J, Majeed A, Wheeler EL, Beck D, et al. eLearning for undergraduate health

professional education: a systematic review informing a radical transformation

of health workforce development. World Health Organization; 2015.

16. Long D, Hunter C, Van

der Geest S. When the field is a ward or a clinic: Hospital ethnography.

Anthropol Med. 2008;15(2):71–8.

17. Minaiyan M, Boojar MMA,

Aghaabdollahian S, Bagheri M. Evaluation of Needs Assessment in Continuing

Medical Education Programs for Community Pharmacists in Isfahan, Iran. J Med

Educ. 2020;19(2).

18. Shaw T, Long A, Chopra

S, Kerfoot BP. Impact on clinical behavior of face‐to‐face continuing medical

education blended with online spaced education: a randomized controlled trial.

J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2011;31(2):103–8.

19. Al-Balas M, Al-Balas HI,

Jaber HM, Obeidat K, Al-Balas H, Aborajooh EA, et al. Distance learning in

clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: current situation,

challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–7.

20. Anderson T. Towards a

theory of online learning. Theory Pract online Learn. 2004;2:109–19.

21. Zehry K, Halder N,

Theodosiou L. E-Learning in medical education in the United Kingdom.

Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2011;15:3163–7.

22. Schiller JS, Lucas JW,

Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for US adults: national health interview

survey, 2011. 2012;

23. Emami Sigaroudi A,

Kazemnezhad-Leyli E, Poursheikhian M. Compare the effect of two electronic and

traditional education methods on first principles of instruction in nursing

students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences in 2016. Res Med Educ.

2018;10(1):48–55.

24. Könings KD, Brand‐Gruwel

S, Van Merriënboer JJG. Towards more powerful learning environments through

combining the perspectives of designers, teachers, and students. Br J Educ

Psychol. 2005;75(4):645–60.

25. Fardanesh H,

Ebrahimzadeh I, Sarmadi MR, Hemati N, Rezaee M, Omrani S. A study to compare

learning and motivation of continuing medical education in the medical

university of Kermanshah using the traditional instruction, instruction

designed based on Merrill’s, Reigeluth’s models and Merrill’s, Reigeluth’s

& Keller’s models. J Educ Scinces. 2013;20(1):117–36.

26. Regmi K, Jones L. A

systematic review of the factors - Enablers and barriers - Affecting e-learning

in health sciences education. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–18.

27. Vasili A, Farajollahi M.

A comparative study of the effects of two educational methods, PBL and E-PBL on

the learning of cardiology ward interns. Iran J Med Educ. 2015;15:9–18.

28. Vallee A, Blacher J,

Cariou A, Sorbets E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical

education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res.

2020;22(8):1–19.

29. Wolf AB. The impact of

web-based video lectures on learning in nursing education: An integrative

review. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39(6):E16–20.

30. Wu P, Kuo C, Wu P, Wu T.

Design a competence–based Networked Learning system: using sequence Control as

Example. Curr Dev Technol Educ. 2006;2:787–91.

31. Green SM, Weaver M,

Voegeli D, Fitzsimmons D, Knowles J, Harrison M, et al. The development and

evaluation of the use of a virtual learning environment (Blackboard 5) to

support the learning of pre-qualifying nursing students undertaking a human

anatomy and physiology module. Nurse Educ Today. 2006;26(5):388–95.

32. Rabiepoor S, Khajeali N,

Sadeghi E. Comparison the effect of web-based education and traditional

education on midwifery students about survey of fetus health. Educ Strateg Med

Sci. 2016;9(1):8–15.

33. Goyal S. E-Learning:

Future of education. J Educ Learn. 2012;6(4):239–42.

34. Rossing JP, Miller W,

Cecil AK, Stamper SE. iLearning: The future of higher education? Student

perceptions on learning with mobile tablets. 2012;

35. Müller C, Mildenberger

T. Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online

learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher

education. Educ Res Rev. 2021;34:100394.